Fusion Reactor Waylaid by Latest Waves of Covid Pandemic

(Bloomberg) -- The world’s biggest science project is facing higher costs and testing delays after recurring waves of the Covid-19 pandemic snarled supply chains.

The $22 billion International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, or ITER, under construction in southern France is being funded by 35 countries. They’re counting on the reactor to prove whether limitless quantities of clean energy can be generated by mimicking the power that makes stars shine -- a potential panacea to slow global warming on Earth.

“Despite our best efforts I expect we will have some delay,” ITER Director General Bernard Bigot said at a media briefing on Monday, without elaborating. The French physicist expects to deliver a full impact assessment by the end of the year that will include higher cost estimates.

The delay comes at a time when the U.S. National Academy of Sciences is calling on the U.S. government to accelerate plans to start generating electricity with a pilot fusion plant by 2040. To reach that goal, engineers would have to agree on a viable design over the next seven years, according to a report published last month.

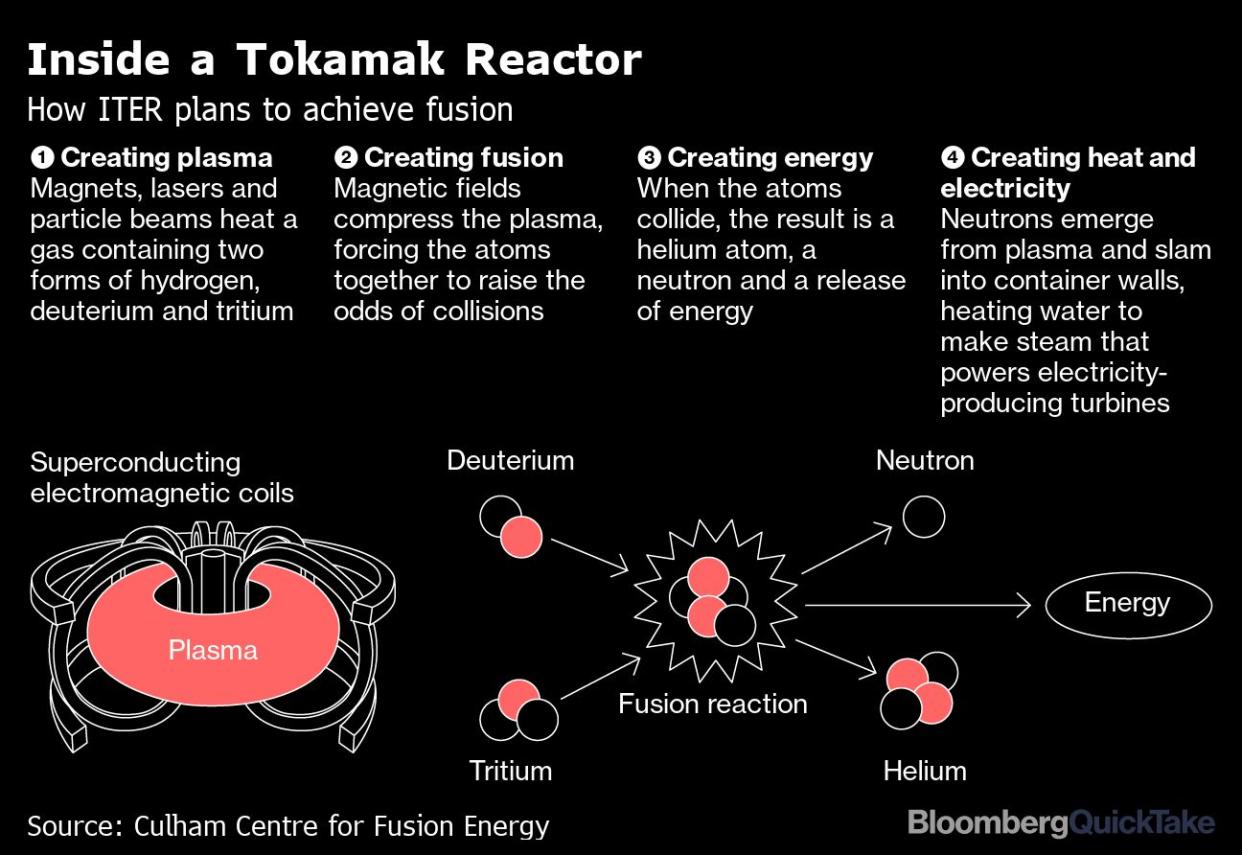

Unlike traditional nuclear plants, which generate power by splitting atoms inside fission reactors, ITER aims to fuse atoms together at 150 million degrees Celsius (270 million degrees Fahrenheit), 10 times hotter than the sun. The reactor, called a tokamak, is derived from designs first tested in the Soviet Union. Lasers and powerful electromagnets are arrayed around a supercooled, doughnut-shaped container to hold superheated plasma in place.

Bigot said the U.S. National Academy’s proposal should be seen as “complementary” to the ITER project. “We believe it is this type of ambitious target that can drive progress,” he said.

It’s not the first time that ITER has faced delays. In 2016, the project got an additional five years and $4.5 billion in funding to undergo its first testing in 2025. Cost estimates more than doubled from the time the project was approved in 2006 to when the project in Cadarache, France, began to get under way.

The latest setback is unlikely to prompt governments to reconsider their support for the project, according to Bigot.

“Even with the Covid impact, it’s given us the chance to assess more precisely than before the feasibility the key technologies,” he said. “We can no longer afford massive use of fossil fuels. All governments are aware of that.”

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.