The G-Man who kept Detroit safe from Hitler’s spies during World War II

This is the first of two Flashbacks on John Bugas, who led the FBI in Detroit during the 1940s then served as a close aide to Henry Ford II. Part II will run next Sunday, Jan. 28.

When she stepped off the train in Detroit on Nov. 1, 1941, Grace Buchanan-Dineen appeared in every detail to be a sophisticated young beauty descended from French nobility fleeing war in Europe.

The 32-year-old Canadian was an unmarried woman from a family of wealth and privilege. She claimed to be a countess, saying her father’s grandfather was the last Count de Neen of Brittany. In an upper-crust French and English accent, she pronounced her first name not to rhyme with “ace,” but as “Grawss.” She had a contract as a lecturer on European manners and style.

Buchanan-Dineen knew no one in Detroit but she had an address book with contacts for her secret mission: to spy for Adolf Hitler.

She was sent to gather information on America’s military-industrial complex. Detroit, with its industrial might and sizable population of German immigrants, was the logical place to base her operations.

What she didn’t know was that she’d been under surveillance by the FBI since shortly after she arrived in New York via the Atlantic Clipper from Lisbon four days earlier.

Spies infiltrated Detroit

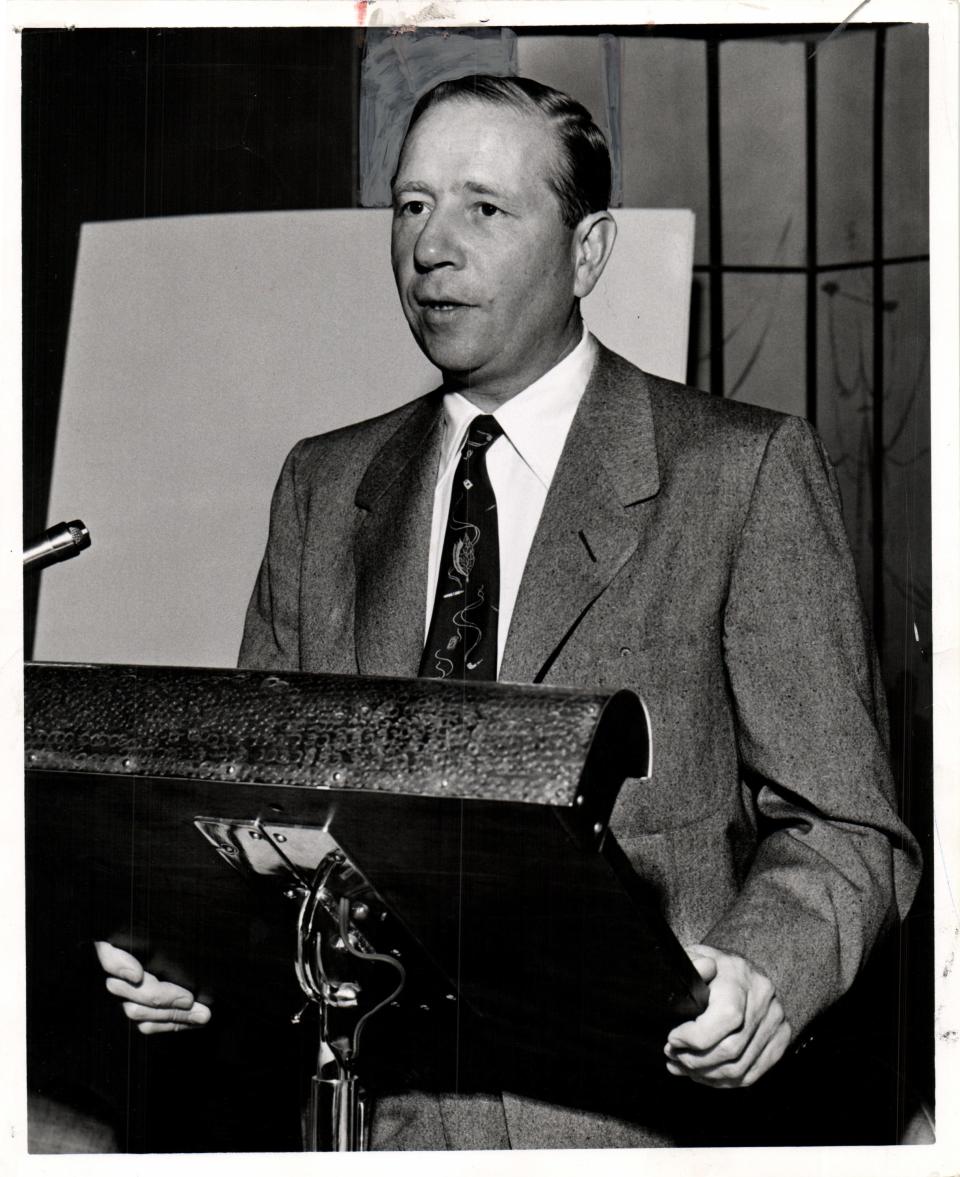

The countess affair was “a bizarre plot,” John Bugas, the FBI special agent in charge in Detroit, told reporters. “It will sound like storybook reading; it is so fantastic.” Indeed, the case was the basis for a 2007 historical-fiction novel by author Margit Liesche, “Lipstick and Lies.”

Sent to Detroit in 1938 by J. Edgar Hoover, Bugas is perhaps the most consequential lawman in Detroit history. He led the fight against mobsters, corrupt politicians, auto plant theft rings and, with the war, Nazi spies. In 1940, he disrupted a plot to blow up a Dodge factory making military material.

Two days after Pearl Harbor, Bugas played a key role in breaking up a New York-based spy ring, including arresting 38 Germans and two Italians as “dangerous aliens” in Detroit. His undercover agents visited virtually every German establishment in town, looking for pro-Nazi hotheads and confidential informants.

In 1942, Bugas participated in many of the 120 raids at the homes of German immigrants suspected of espionage. Dozens of suspects were detained and an impressive collection of guns, short-wave radios and cameras was seized. That year, 56 people were convicted of espionage in Detroit.

“We were losing the war at that time,” Bugas said later. “We were using every method we could to counteract the efforts of the Nazis — and felt completely justified.”

Growing up on his family ranch in Wyoming, Bugas had what family members called a “cowboy morality,” ready to mete out justice to bad guys, both on the job or in his private life. With the FBI, he earned several commendations for his part in solving bank robberies and kidnappings. In Glendale, California, he personally arrested at gunpoint a kidnapper described by the FBI in 1936 as Public Enemy No. 1.

Bugas “was a fearless investigator, adept at the art of fisticuffs while wearing a suit,” wrote A.J. Baime in his 2014 book about Detroit’s contribution to the war effort, “The Arsenal of Democracy.”

The countess was a double agent

The countess Buchanan-Dineen was born in Canada in 1909 and educated in a French convent. She traveled throughout Europe with her wealthy father before his death in Budapest in 1939.

In May 1941, she was recruited by a Gestapo-connected German-Hungarian couple who had developed a network of contacts in the U.S. Her training in Berlin included her “cover story” as a countess lecturing to society groups on European manners and current affairs. Her topics included “War Torn Europe,” “The Oppression of War,” and “I saw Nazis in Central Europe.”

In Detroit, her primary contact was Theresa Behrens, a German immigrant who was the secretary of the International Center at the YWCA. “No one in the Detroit group was more active than she in lining up sources of information” for Germany, the FBI said.

The FBI secretly arrested Buchanan-Dineen on March 5, 1942, and Bugas persuaded her to betray her co-conspirators and to transmit false information to Germany that he would provide. The FBI set her up in a fancy riverfront apartment and installed microphones and a hidden camera behind a one-way mirror to ensnare co-conspirators.

Just a few weeks later, the Free Press published an article that said Buchanan-Dineen would be the guest speaker at a meeting of the Women’s Advertising Club. “She is really a countess, but the title cannot be used outside of France,” a member said.

“Miss Buchanan-Dineen’s personality and extensive travel made her an excellent conversationalist and a person who was found interesting by a number of socially prominent persons with whom she came in contact,” a government document said.

“She dressed nattily and told of her European experiences with a delightful Oxfordian accent,” wrote Free Press librarian Morgan Oates in 1960. “She leased one of Detroit’s most fashionable apartments and was soon circulating in the best of circles.”

That’s pronounced ‘grawss,’ darling

Meanwhile, the FBI was rounding up other Nazi operatives. They seemed better suited for a farce than a spy thriller.

Max Stephan, owner of the German Restaurant near Belle Isle, was charged with harboring a fugitive after he helped a Luftwaffe pilot who had escaped from a Canadian POW camp. At Bugas’ request, the charge was increased to treason, which carried the death penalty.

Strangely, instead of hiding the escapee in his basement, Stephan had taken the pilot out in public — still dressed in his POW overalls — for food and drink and paid for his visit to a brothel near the Fox Theatre.

His trial featured witnesses that included the pilot himself, who testified in full Nazi uniform complete with swastika. Nobody knows how he got the uniform while in custody.

Just eight hours before Stephan was to hang, President Franklin D. Roosevelt commuted his sentence to life in prison.

Buchanan-Dineen’s work as a double agent brought her no benefits. She was arrested again in August 1943, along with Behrens and Dr. Fred Thomas, a Detroit obstetrician and a Nazi fanatic known for hectoring a rabbi with antisemitic propaganda.

In September, four others were indicted in the spy ring, including another “countess,” Mariana von Moltke, who was married to an actual count teaching German at what was then Wayne University.

The trial was held in January 1944. Behrens provided histrionics, declaring a hunger strike and fainting in the courtroom. Expecting a break, Buchanan-Dineen testified that she’d helped the FBI and implicated her co-defendants. Despite that, she and the others were found guilty and given lengthy prison terms.

The convictions of two spies were overturned due to improper jury instructions, but the government decided against a retrial because Buchanan-Dineen refused to testify again. She “is embittered and irreconcilably hostile,” a government memo said. Besides, the ring had provided no useful information to the Germans.

“When she was deported in 1948, she retained much of her haughty charm and cold glamour,” wrote Oates.

Buchanan-Dineen’s fashionable dresses, furs and jewelry were packed into a large trunk and 16 pieces of luggage loaded onto a train bound for Toronto.

At the gate, she turned to reporters to remind them her name was pronounced “Grawss.”

Next week, Part Two: John Bugas saves the Ford Motor Co. from the notorious Harry Bennett.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: John Bugas, the FBI agent who caught Hitler’s spies in World War II