Police failed us, say parents of public schoolboy after mysterious balcony death

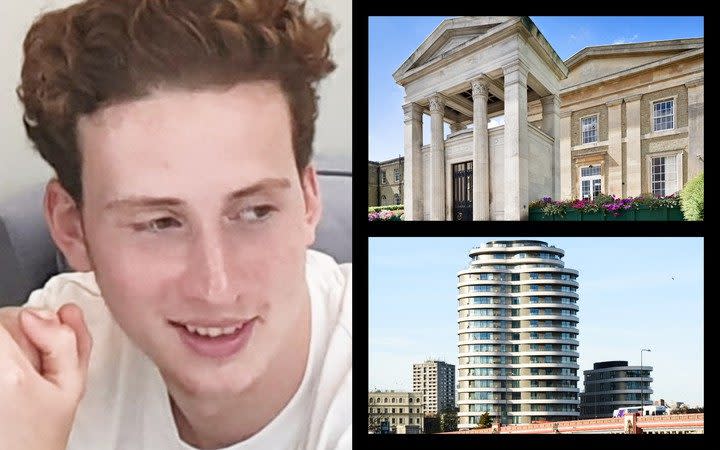

At 2.24am on Nov 29 2019, 19-year-old Zac Brettler jumped from the fifth-floor balcony of Riverwalk, an apartment block on the Thames opposite MI6 headquarters at Vauxhall. The event was caught on one of the MI6 security cameras. Zac had spent the evening with a businessman, Akbar Shamji, and a gangster, Dave Sharma, whose flat it was. In the footage, he comes out onto the balcony, looks over both sides, and then jumps from the centre. The fall killed him.

A forensic report later determined that Zac nearly made it into the river, but clipped his hip on the wall of the embankment. Initially the death was recorded as suicide. Zac’s parents, Matthew and Rachelle, both 61, were sure it was not. Zac could be eccentric, and had lately been sucked into a London demimonde of crooks and charlatans, but they were adamant he was not suicidal.

“There was nothing in Zac’s life that had ever suggested anything suicidal,” Matthew tells The Telegraph. “It’s not a question of Rachelle and me finding it hard to think he would want to commit suicide. That’s not what is driving this. But [suicide] didn’t feel right.”

The Brettlers, who live in Maida Vale, north London, have spent the four years since trying to find out what happened to their son that night. Matthew is a director of a financial services company; Rachelle is a journalist. They have another son, Joe, who is nearly two years older than Zac.

Until now they have avoided the press, but they have come forward in the hope of bringing what they see as institutional incompetence to wider public knowledge. Their case was the subject of a long feature by the award-winning journalist Patrick Radden Keefe, published in The New Yorker this week. Now the Brettlers hope that with further attention, the police might be forced to reopen a case that, from the outside at least, seems riddled with inconsistencies.

“We put our faith in a process and we don’t feel that faith was in any way vindicated,” Matthew says. “It has essentially been abused. We knew we had lost our son, and nothing was going to bring him back. We wanted to force some accountability on the police. This isn’t the first instance of them not doing the job that we as the public expect them to do. It was very hard to understand why the police acted as they did.”

Twenty-one minutes before the fall, Zac had emailed Rachelle, replying to a message she had sent about him leaving his wallet and keys behind at the family home in Maida Vale. “All good x”, Zac wrote.

The events that took place between Zac’s last message and his body being identified forms much of the mystery at the heart of the case.

On the morning of Nov 29, hours after Zac jumped, a chauffeur turned up at the Brettlers’ front door asking for Zac. Rachelle explained she was Zac’s mother. The chauffeur was on the phone, and Rachelle heard another man’s voice say: “That can’t be his mum. His mum is in Dubai.” The chauffeur drove off without further explanation. It was the first inkling Rachelle had that her son had been living a double life.

That afternoon, Rachelle reported Zac missing. Four days later, he still hadn’t shown up. Police had found a body in the Thames, but had not yet connected it with the missing person case.

Through a mutual friend, the Brettlers arranged a meeting with Shamji. He said that he was worried about Zac, too. He told them that earlier in the evening Zac had confessed to a heroin addiction. This was news to Matthew and Rachelle, who had seen no sign of any drug problem. But Shamji was a slick 47-year-old, who had gone to the University of Cambridge. His father Abdul had been a wealthy businessman and Tory donor, albeit one briefly jailed for fraud. But Shamji seemed like a creditable figure.

More alarmingly still, Shamji said he had known their son not as Zac Brettler but Zac Ismailov, the son of a Russian oligarch. Until the Brettlers had made contact, he had thought Zac’s father had recently died and his mother was living in Dubai. Evidently the Brettlers had lost touch with the life their son was living.

The next day, a police car pulled up outside the Brettlers’ home. Two female police officers got out. One of them held Rachelle’s hand while she told her the news.

Matthew says while the initial police investigation was rigorous, it petered out as the case wore on. “[A verdict of suicide] was an easy out for the police. And then in order to substantiate the suicide side of things, they went into victim-blaming mode, saying that [Zac] was a troubled kid,” he says. “They made comments like, ‘He didn’t have much going on in his life.’ It was nonsense, based on nothing. Armchair psychology.

“The overwhelming evidence pointed to foul play and away from suicide.

“As public servants, in whom we vest our confidence and faith to carry on investigations on our behalf when bad things happen, [the police] completely failed. That’s what has been driving us. Some light needs to be shone on the police and they need to be held to account. They showed a lack of curiosity in the way they investigated things. You’d have thought curiosity was the first prerequisite of detective work,” says Matthew.

He admits that Zac was “a complex guy”, as he puts it. “He was a very loving and kind kid. Part of him was mono-focussed, and he had this ability to be very compelling, which, plus his incredible imagination, he used to create this alter ego for himself, which we had no idea about.”

Zac had been a bright and sporty boy who loved tennis and cricket. The family had noticed changes in his behaviour after he started at Mill Hill, a school in north London beloved of the children of oligarchs (alumni include Evgeny Lebedev). In that company, Zac became fascinated by wealth, demanding that his parents bought a bigger house or a fancier car. In 2018 he moved to Ashbourne College, in Kensington, for his final year of school. By then, he had started bragging to his parents about business deals he was involved in, to do with cars and property. They did not know if he was telling the truth. He was also behaving erratically, becoming argumentative and, on one occasion, physically violent towards his mother, placing his hands around her throat.

By early 2019 Zac had befriended Shamji, a businessman who lived in Mayfair. Zac told his parents that he and Shamji were business partners, looking at everything from mines in Kazakhstan to skincare products. In July, Zac moved into a flat in the Riverwalk complex. He told them he was renting the flat from a friend, Verinder Sharma, a rubber tycoon from India. He was talking about skipping university, as he was making so much money from his deals.

Verinder was the birth name of Dave Sharma, a gangster. In 2002, Sharma had been arrested, along with several others, on heroin-smuggling charges. During the trial, only one of the suspects was not prosecuted: Dave King, a nightclub owner. In court, Sharma angrily referred to King as a “grass”. A year later, King was mown down with an AK-47 as he left a gym in Hertfordshire. Moments after the shooting, the assassin – who, along with the driver, was sentenced to life in prison – rang a mobile phone in France that was connected to Sharma.

Sharma and Shamji were both arrested after Zac’s death. Sharma provided a handwritten statement saying he had passed out drunk and woken up at 8am. When officers entered the apartment, they found it spotless, including an area on a glass partition near where Zac had jumped from, which seemed to have been recently wiped clean. Sharma had visible injuries on his face.

Examining their phones, investigators found activity that contradicted their accounts. At 2.12am, three minutes before the fateful jump, when Sharma had told police he was asleep, he had phoned Shamji, who was on his way back to London in the car. Whatever was said alarmed Shamji enough that he turned the car around. CCTV footage shows that he got back to the flat at 2.34am, went upstairs and then reappeared 20 minutes later. Before he drove off, he looked over the railing on the riverside, right where Zac had jumped.

When questioned about these events, Shamji said he had gone back to “say goodnight”. He initially claimed to have seen Zac on this visit, but changed his story when it was pointed out this was impossible. When he was asked about his walk to the riverside at 3am, he said it was a “nice bit of river”.

Other discrepancies piled up. Sharma did not sleep until 8am, as he had claimed. He was texting Shamji again by 6.50am. At 8.10am, the Riverwalk concierge, Ana Nunes, says Sharma called her to ask if someone had jumped from the balcony. Evidently he knew something was up. Yet while he and Shamji exchanged several messages afterwards, when Shamji met the Brettler parents in Piccadilly, when Zac was a missing person, he made no mention of the corpse that had been found on the riverbank directly below the flat. Nor did Shamji or Sharma tell police that the victim might have fallen from Sharma’s balcony.

A pathologist’s report on Zac found no traces of heroin in his system, contradicting Shamji’s claims that he’d had a drug problem. (Earlier, when Matthew and Rachelle had been growing worried about their son’s behaviour, they had surreptitiously drug tested him and even secretly filmed him while they were on holiday in Oman, but discovered nothing suspicious.) As well as the hip injury where he had hit the embankment on the way down, Zac had a broken elbow and a broken jaw, the latter of which could not easily be explained by the fall.

Sharma and Shamji were released on bail. Zac’s funeral was held in Golders Green, a few miles from their home. His death attracted zero press coverage, perhaps because it initially looked like a teenage suicide with no public interest. Matthew and Rachelle did not seek publicity, assuming that the authorities would pursue the case with proper diligence. This may have been naive. Zac’s was one of a clutch of suspicious “suicides” in recent years. Without firm evidence to the contrary, the police seem happy to let these deaths be.

Frustrated by police inaction, the Brettlers hired a private investigator and spoke to Zac’s friends. One, who had seen him two days before he died, said Zac was afraid for his life. Police recovered an iPad among Zac’s possessions, where a recent search was for “witness protection uk”.

It became clear that Zac had been more of a fantasist than he had ever let on: telling classmates that his mum was dead, and that his father was an arms dealer, and that New Balance were going to sponsor him to play cricket. As he got older, these lies had hardened into something more risky. In early 2019, at a party at the Chelsea Arts Club, Zac met a consultant who had worked in the world of football and was well connected in the oligarch world. It seems Zac decided, perhaps spontaneously, to pretend he was the son of an oligarch, with access to huge capital reserves. This is where the Zac Ismailov persona was apparently born, with the name taken without their knowledge from a neighbour of Shamji’s.

It was in this Ismailov guise that Zac was introduced by the consultant to Shamji, who was looking for funding for a property project in Lisbon. It’s unclear the extent to which Shamji knew Zac was living a lie. He introduced him to Sharma. Over the summer of 2019, Zac enjoyed his rent-free accommodation and lavish lifestyle, on the presumption that he might one day make Shamji and Sharma a lot of money.

Messages exchanged between Shamji and Sharma in the days leading up to Zac’s death show they are increasingly anxious. Sharma texted Shamji saying: “Akbar I want 5 per cent of that 205 million and that’s it.” They evidently feared their goose may not have been as golden as they had hoped. On the morning of Nov 28, Sharma messaged Shamji saying: “I’m thinking f--k this little kid.”

At 10.35pm that night, hours before Zac died, Shamji messaged another friend saying “I have just been heating up knives and clearing up blood,” and adding later “s--t’s about to go wrong! Wrong!”

The Brettlers’ theory is that their son jumped to escape rather than kill himself. Zac was trapped in the middle of the night with a dangerous gangster, who had realised he had been led on a merry dance by a teenager who was not as rich as he had said he was. To reach the river from the balcony, you would have to jump outwards 6ft or so. Not impossible, and certainly not in the desperate mind of a fit, athletic 19-year-old. If it had been suicide, he would have fallen straight down rather than graze the embankment.

Any hopes the Brettlers harboured of getting to the bottom of what happened the night Zac died were dashed in December 2020. Matthew was at home in Maida Vale when he received a call from the lead detective on Zac’s case. Sharma had been found dead in his flat, of a drug overdose that might have been suicide. To this day, the authorities have remained mysteriously silent about what happened, despite Sharma’s dubious history. Matthew told Keefe that he found “the approach adopted by the police to be completely mind-blowing”. He wondered if Sharma had been a police informant.

The police showed a similar reluctance to pursue Zac’s death, despite the suspicious circumstances. They never interviewed the chauffeur who showed up in Maida Vale hours after Zac died, or the consultant who facilitated the introduction. When the Brettlers questioned the lead detective about the case in February 2022, he expressed sympathy but explained that he didn’t have enough evidence to support a murder case. “It feels like you’re interrogating me,” he said at one point.

“It was one of those ‘joke not joke’ comments,” Matthew says. “As soon as he felt under pressure he started saying things like ‘I think the crisis was with Zac’. Zac was just 19, and he was with a 55-year-old at least former gangster and a 47-year-old guy, Shamji, who was a serial sleazeball. And yet the lead detective chooses to see Zac as the puppetmaster. It was absurd.

“Zac wasn’t the seasoned guy who’d been around the block. He was a kid. Yes, he had a fantasist side to him. I’m sure Zac got a kick out of being in the presence of Sharma. I find that hard to accept about my son, but I have to accept it. But for them to turn this around and say this was all about Zac and not to see that something seriously wrong had gone on and Sharma was very angry…

“How can he sit there and tell me stuff like that,” he adds. “It’s just incredible. I’m not the sort of parent who can’t see any wrong in my child. It’s not a question of me being unwilling to accept some harsh realities about my child. That’s not what this is about. It’s about a police officer ignoring the hard data points that have been thrown up.”

Keefe, who wrote The New Yorker piece, says that the Brettlers are unusually clear-eyed when it comes to Zac. “I spent five months talking regularly to Matthew and Rachelle,” he says. “I’ve written pieces before with family members who seem like they are in denial. They didn’t seem like that at all. They were very open about the darker sides of Zac.”

Later in 2022 there was a public inquest about the death, presided over by a coroner. Shamji appeared by video link, speaking for hours but throwing no new light on the situation. The coroner concluded that Zac had been “obviously scared” before he died and that Shamji was “looking for Zac” when he peered over the railing. After two days the coroner recorded an “open” verdict, which is that they would not speculate on whether it was suspicious or suicide.

Matthew views the coroner’s inquest as another example of the authorities glossing over inconvenient facts in the name of expediency.

“They showed no interest – it felt like all they wanted to do was get the thing over with,” Matthew says. “I’m absolutely convinced they had made their mind up before we got going, and what their conclusion would be. They had that air about them that this was all such an irritation. We thought there was going to be a genuine spirit of inquiry and that was completely lacking.” The Coroner’s Office has been approached for comment.

Having come forward, Brettler says he does not want to become a campaigner, but hopes public interest in what happened to Zac might lead to a re-examining of the facts of the case. “The first-level objective was to hold this up for public review,” he says. “In an ideal scenario, somebody in the upper echelons of the police, or maybe a politician, would say ‘hang on a second, we should be doing better by the public’.”

Although they have only recently chosen to go public, as they investigated Zac’s case the Brettlers have benefitted from having the money, time and connections to challenge the authorities when they have felt unhappy. They have still been let down. As Keefe says, “The irony of Zac feeling as though he wasn’t well off enough is that the Brettlers are pretty comfortable. They’re pretty privileged and well connected. If this can happen to them, what should we intuit about what would happen to an immigrant family or a homeless family?”

Whatever happens next, the case has irrevocably altered Brettler’s view of London, and the British authorities, as well as bringing tragedy to his family. “This process of doing investigative work because the police haven’t, has opened my eyes to this grey world,” he says. “There are characters around who know something. I don’t know what they know, but they know something. They’re right on my doorstep. I’m not suggesting London is alone in having this underbelly, but I had been unaware of it. And once you’ve seen it you can’t unsee it. It’s that sense of London selling its soul for money.”

A Met Police spokesperson says: “Our sincere condolences remain with Zac Brettler’s family, and we understand the uncertainty about how their son died must continue to be the cause of unimaginable pain. Whenever someone dies unexpectedly in London, we have established policing protocols to follow, and the investigation into Zac’s death was led by an experienced detective.

“The team worked hard to explore every possible hypothesis, which were shared with Zac’s family, but ultimately we were not able to provide fuller answers.

“The case was also reviewed by specialist homicide detectives to ensure every line of inquiry had been exhausted. As with any case, we would always encourage anyone who they believe has additional information or evidence to contact police. Any new information will be examined on its own merit by a team led by experienced detectives.”

“Zac was a smart and talented kid,” Matthew says. “It’s a waste of a life. I know he’d had this fantasist existence, but he’s not the first person who’s had a developed sense of fantasy. I would have hoped that that side of him could have been applied in a more productive area. My overwhelming emotion is of what might have been.”

Sharma’s death means the Brettlers will never know for certain what happened to Zac. But an open verdict does not mean that there aren’t still answers out there, waiting in the grey world.

*Akbar Shamji has been approached for comment