Gans, Shapiro debate the McCutcheon campaign finance case

Should the Supreme Court expand or even eliminate campaign finance limits made by individuals? Ilya Shapiro from the Cato Institute and David H. Gans from the Constitutional Accountability Center sit down with the National Constitution Center’s Jeffrey Rosen to debate key issues in the McCutcheon case.

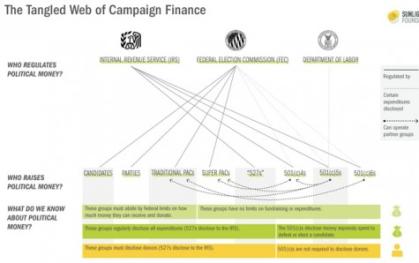

Sunlight Foundation campaign finance explanation chart

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard arguments in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, a case that could rewrite campaign finance laws.

The precedents were set primarily in two Supreme Court rulings in 1976 and 2010.

In 1976, the Court ruled in the case of Buckley v. Valeo that Congress had extensive power to put limits on individual campaign donations to federal candidates as a way to prevent corruption. But the Court couldn’t restrict expenditures, independent of candidates, by individuals and groups.

And, in the 2010 case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the Court said that corporations and labor can spend just as much as they want on independent efforts to influence federal election outcomes, and this would not be corrupting.

Rosen conducted this extended interview with Gans and Shapiro on Wednesday, a day after the Court heard arguments in McCutcheon. Here is the full audio of the discussion between Rosen, Gans, and Shapiro. (Click on this link if you can’t use the player below.)

PLAY AUDIO

Rosen: Should the distinction drawn in Buckley v. Valeo, between limitations on campaign contributions, which are permissible, to prevent corruption and limitations on campaign expenditures, which are not, be maintained, or should Buckley be overruled, as Justice Thomas and others have signaled?

Shapiro: Thanks for that question, Jeff, that exactly tees up our brief which I think goes broader than what the court will necessarily have to decide in this case. I do think that Buckley rewrote the legislation that was passed in the wake of Watergate and created the modern campaign finance system which has been later amended by legislation and court decision in a way that makes for an unstable and now an increasingly unworkable system.

I don’t think that the distinction between expenditures and contributions on a constitutional, First Amendment level, can really be maintained, because after all just like banning the printing press or access to the Internet can be a violation of the First Amendment, restricting or banning money that is facilitating political speech also raises the same sorts of concerns.

So I think that this is a fairly easier case in that respect about the aggregate limits, why can max out to nine candidates but one more dollar to that 10th one all of a sudden becomes corrupting.

But the broader issue that you raise is in the shadows here and might come up in the future, fundamentally in terms as a matter of policy and as a matter of First Amendment law we will have to rethink the Buckley framework.

Rosen: David, what do you think about the claim that the Buckley framework should be overturned, and tell us more about whether the Buckley framework rests on an unnecessarily narrow notion of corruption.

Gans: First, I want to point out the claim that Ilya is making which was often made to some extent by the Republican National Committee as well as Senator McConnell is really a radical one that has never been accepted by any court in history. There is no court that has said you have as a matter of the First Amendment’s freedom of speech the right to make unlimited campaign contributions.

And I think that rests on a very common sense view that campaign contributions are a petri dish for corruption. That is something we’ve seen in Watergate which led to the campaign finance laws and we’ve seen that all the way back to the Gilded Age. That has never really been our understanding of freedom of speech. And one of the things that is telling is you didn’t see Justice Scalia or Justice Kennedy offer any understanding why the First Amendment gives that same protection to campaign contributions, never articulated that First Amendment sense. That is something I thought was very much missing. The case was focusing very intensely on corruption.

I think really the answer the court needs to address is let’s not just make up our own understanding of corruption, let’s look at the Constitution’s text and history. One of the things many people are not very aware of is that framers were very intensely concerned about corruption, and the debates over the Constitution revolved to a great deal over how the government could be created that would prevent corruption.

That was one of the framers’ leading concerns, and they created a representative democracy that was by, of, and for the people, as Madison said, not for the rich, more than for the poor, and they were concerned that the government could be corrupted by improper dependence on the few. That might be foreign patrons, that might be local factions. I think that the great concern about McCutcheon is you strike down these aggregate limits and you open the door to multimillion dollar contributions. As General Verrilli pointed out, these limits are a bulwark against a system in which donors can cut multimillion dollar checks. The court upheld these aggregate limits in Buckley and they should do so here as well.

Rosen: Ilya, let’s focus in on David’s very interesting claim, which appears in the brief filed by the Constitutional Accountability Center, that the framers of the Constitution would have supported broad limits on contributions and expenditures because the corruption they were concerned about combating was not just about quid pro quo corruption—take this contribution and get me a land deal—it was a broader concern about what he calls dependence corruption, that basically the entire structure of government would be dependent on particular cabals, aristocratic people, rich people, and citizens would lack trust in them. You reject that notion in your brief. Tell us why a good originalist like Justice Scalia or Justice Thomas shouldn’t be persuaded by David that the framers of the Constitution would have defined corruption as broadly as he says.

Shapiro: The Constitutional Accountability Center’s brief is very interesting on behalf of Professor Larry Lessig of Harvard. I have talked about these issues with Professor Lessig and it is an accurate, historical presentation of the definition of corruption and what the Founders thought about it. But you have to remember that was a different political age. The franchise, the right to vote, was limited to propertied gentlemen of a certain class, the way that elections were conducted you got your voters essentially drunk, you had a lot of spirits lined up, and the ballot wasn’t even secret. So there are a lot of things that are different about the political process then than now.

There were these concerns about systemic corruption, while still certainly present and valid in the abstract, I think are taken care of by other laws we have in respect to voting rights. With respect to disclosures, I think it would be great to let those handfuls of people who want to spend their money on the political process, maybe they should be donating to Cato or the National Constitution Center, or the Constitutional Accountability Center instead. But anyhow, they want to do that. Let the voters then decide whether they want to vote for a candidate who is wholly financed by George Soros or Sheldon Adelson, or whoever the case may be. I think this is really a solution in search of a problem, this attempt to have these aggregate limits. That is an easier case than individual limits on a candidate. But it seems strange that you can spend a 120,000 dollars but one more dollar to one more candidate all of a sudden starts corrupting the system.

Rosen: David, you just got high praise from Ilya on the Lessig brief, he says that is historically accurate, but times have changed.

Gans: There are aspects of our constitutional system that have changed, and we’ve certainly have had all sorts of amendments that have given greater protection to the right to vote, and the Supreme Court should be paying more attention to those than it does.

But there is no reason we should reject this fundamental principle that Madison sets out, that this is a representative democracy that is not for the rich more than the poor. And the question is, will the Supreme Court, will originalists like Justice Scalia, live up to that, or will they say, $3.6 million to us doesn’t seem like a lot when that is one percent of the one percent of the one percent for most people having the ability to put that kind of money into the political system. It’s just not feasible. It distorts the representative democracy that our Constitution forms.

Rosen: I’ll put the question back to Ilya. You suggest that Justice Scalia says the Constitution means what it meant in 1787, so he’s not a living constitutionalist and Ilya, is it appropriate for Scalia or Justice Thomas to embrace the argument you just made that time have changed.

Shapiro: It’s not that the Constitution had changed. Let’s be clear about that. It’s not that there was a scheme to limit total campaign donations or some sort of equivalent to McCain-Feingold or the Buckley v. Valeo era framework that we can just transpose. We have to understand is how do you take those concerns about systemic corruption, what do those very valid concerns mean in the present day.

In the present day, that means certainly you don’t allow vote buying, certainly you don’t allow quid pro quo corruption. There are a lot of concerns with lobbying, for example, on the back-end. Ten to 12 times more money is spent on lobbying than is on campaigning.

So you have to look at things more systematically. And also fundamentally see whether whatever concerns, in however your articulation of the corruption or anti-corruption interest is, and comparison to the Founders’ very fundamental belief that political speech is at the core of the liberty the Constitution is meant to protect. I don’t see how these aggregate limits do anything to prevent corruption of the system or any individual politician.

Rosen: David, Ilya makes a strong point. He says OK, I grant that dependence corruption, systemic corruption, is what the framers were concerned about. We just disagree about what will prevent that kind of corruption. And the Cato brief, which is quite strong in its arguments, says that studies indicate that campaign spending doesn’t diminish trust in government, and also that candidates have to spend so much time raising money, given these limits, that it makes them more vulnerable to systemic corruption, and not less. What’s your response to that?

Gans: Let me point out that if Ilya is accepting that our history is right, then by definition Kennedy’s view that the only kind of corruption is quid pro quo corruption is wrong. As our brief shows, among the framers that was rare. The framers were much more concerned about improper dependence. So that is a fundamental point that really goes to the heart of the issues in McCutcheon.

Rosen: Your brief rather magnanimously says our view is consistent with the Citizens United case, but in fact you just suggested that a hard look at Citizens United would define corruption more narrowly than the framers would have.

Gans: Our brief said it was consistent with the result in Citizens United.

Shapiro: This came up in arguments actually yesterday. That’s actually a key point. Breyer, Scalia, Kennedy in yesterday’s argument, they all talked about this weird dichotomy between independent liberalized political speech after Citizens United, and you have this cabin-restricted campaign or party speech, and the average voter can’t really see the difference between them. So what does that mean for the law? The Justices might come out on different ways because of that. But I think that is an important aspect of this case.

Gans: It goes back to the Buckley framework, which was “expenditures were not viewed as corrupting and contributions were.” I think if you apply that framework, which has been reaffirmed countless times, that means aggregate contributions, especially when you are talking about multimillion dollar contributions, do have that inherent corruption potential that should be upheld.

Rosen: Can I ask another point of clarification? Buckley, you both seem to be agreeing, said that limits on contributions are justified because contributions are more likely to corrupt than expenditures. But Buckley also said that caps on campaign expenditures, but not contributions, are restrictions on political free speech. And the reasoning was while contributions may result in political expression, as spent by a candidate or an association, the transformation of contributions into political debate involves speech by someone other than the contributor. And by contrast, expenditure limits represent substantial rather than theoretical restraints on the quality and diversity of political speech. Is it correct that in Buckley the distinction between contributions and expenditures rested not only on a concern about corruption, but also on the thought that there was more expressive content to expenditures than contributions?

Shapiro: I think that is right, I think that is part of Buckley. I would question that, certainly, I think that is part of that distinction. I think it is wrong, because when you make that political contribution you are saying that you agree with that candidate, you agree with that party or policy, or whatever the case may be. It’s not really that different from the independent political speech. It all goes towards same sorts of political ads or what have you.

Rosen: David, do you agree with Buckley that it is second-party speech and therefore expenditures have more First Amendment content than contributions?

Gans: I think what Buckley said was they don’t see it as quite a strong of claim of First Amendment protection than, as say, a campaign ad. The fundamental point is that you are dealing with a direct cash transfer to a candidate, and history tells us that’s the petri dish of corruption. And the government’s interest, especially once we focus on the text and history of the Constitution, the government interest has to be at his highest point in that case. I think if the court kind of reflects both on its precedents and on the text and history, the answer should be the answer in Buckley. These kinds of limits should be upheld.

Rosen: If you were both writing from scratch, where would you draw the line? Like Buckley or somewhere else? Ilya, like the Constitutional Accountability Center, you take text and history seriously at Cato. If the Justices were writing on a clean slate, no campaign regulations at all, and what would be consistent and permissible with the First Amendment?

Shapiro: I have a wry sort of law review article on this called “Stephen Colbert’s right to lampoon our campaign finance system and so can you.” I do think especially with the possibility for instant disclosure and the Internet, and information getting out that unlimited contributions or at least very high ones, indexed to inflation, combined with instant disclosure, above a certain level, I don’t think there is interest in a little old lady donating 20 bucks is outweighed by the potential for harassing her. There are details, technicalities. I do think fewer limits and more transparency is the way to go.

Gans: I think just about everyone can agree the distinction between contributions and expenditures has not been a satisfactory one. I point to one example from yesterday’s argument that Kennedy, after authoring, said that Citizens United suggested, well actually the person who spends millions of dollars on electoral ads might have a greater claim to the politician’s ear than a campaign contributor. Which suggests that there is an answer of only contributions are corrupting and expenditures, by definition, are not, is hard to square with basic common sense and what we see on the ground.

Shapiro: I agree with that point but I would draw the opposite conclusion. If you are going to liberalize independent speech, which I think Citizens United was correct, then you can’t imbalance the playing field in that sort of way. Parties and candidates don’t have any special First Amendment rights, but I think they should have just as much as independent speakers, and that is part of the reason why I think the current system in unworkable.

Rosen: Ilya’s solution is deregulation. David, is yours complete regulation, and would you restrict expenditures and contributions, or would you have another solution?

Gans: I wouldn’t say that. I think the First Amendment balance is one that has to be respected. But you have to attend to both the First Amendment balance as well the interest on the other side of the equation, which is also sort of constitutionally backed. One, in terms of this interest in ensuring that there is a government free of corruption. And I go back to this fundamental point that Madison made, that our government was not to be for the rich more than for the poor. The Supreme Court’s precedents have escalated the tendency in that regard. I think there is more drawing to be done but on the whole there has to be much more respect for the government’s interest in deterring actual and apparent corruption. Part of the problem is that the Justices have really ignored the text and history that makes this plain. I think that is one of the signal importances of our brief, which is to set out this history and show how powerful it is.

Shapiro: Part of it is a factual dispute. We are not just talking abstractly about theory and differing views of history. And in fact, we agree on the history. We just disagree on the interpretation or application to the modern day. But there are about 20 states, give or take, that don’t have restrictions on campaign donations in state campaigns. And there’s no indication whatsoever that those states are more corrupt than other states. For example, Illinois and California, which are remarkable examples now of either corruption or broken government, or what have you, have some of the most severe and regulated campaign finance laws of all. And there are other states in different parts of the country, red and blue, that have gone a different way.

Gans: I would only say the case for federal limits is very much one of responding to massive corruption violations. We have these limits because of Watergate, and wealthy businesses and individuals were pumping huge dollars into the political system, because they saw there were advantages in the political process to be won by that. History shows the need for the regulation of campaign financing to protect against actual and apparent corruption.

Rosen: That is a powerful note to which to end this vigorous debate! David Gans and Ilya Shapiro, thank you so much for a fascinating debate.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Audio interview: Breaking down the McCutcheon case

The Affordable Care Act and a tale of two Constitutions

Constitution Check: Should only U.S. citizens serve on juries?

A look at the Justice Antonin Scalia’s most unusual word choices