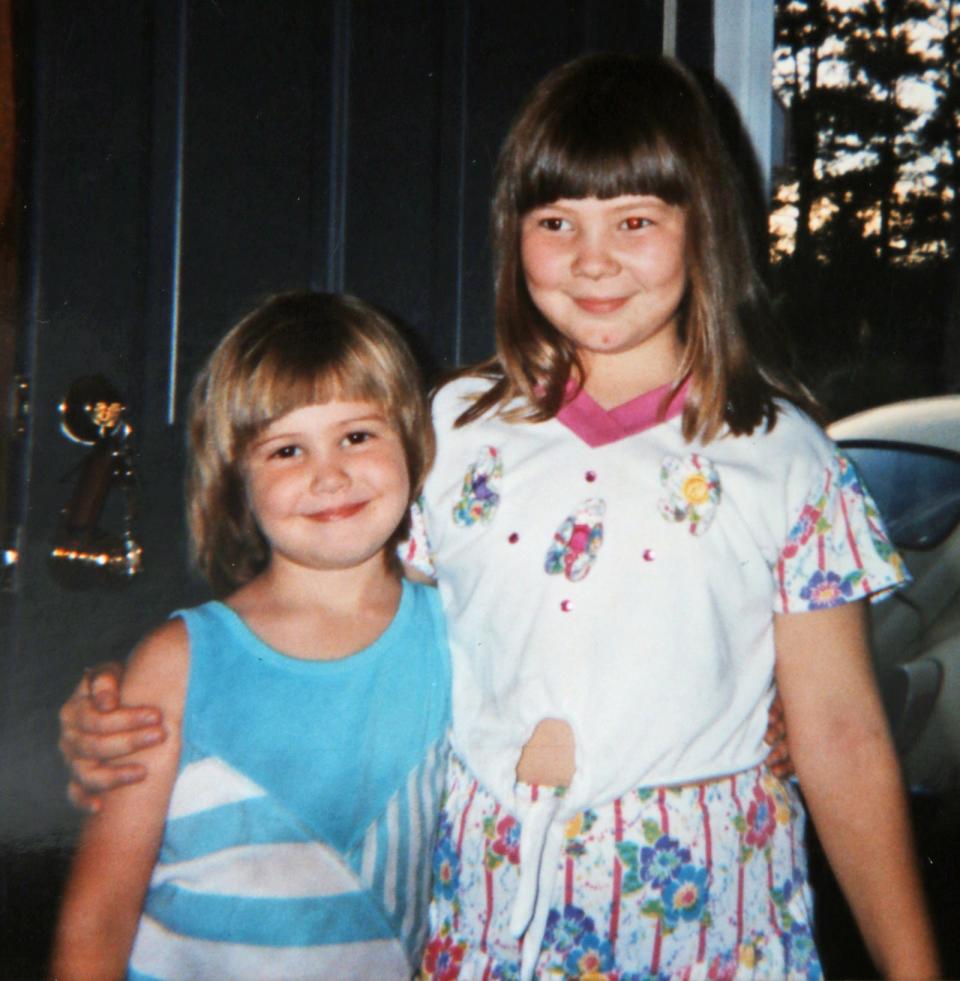

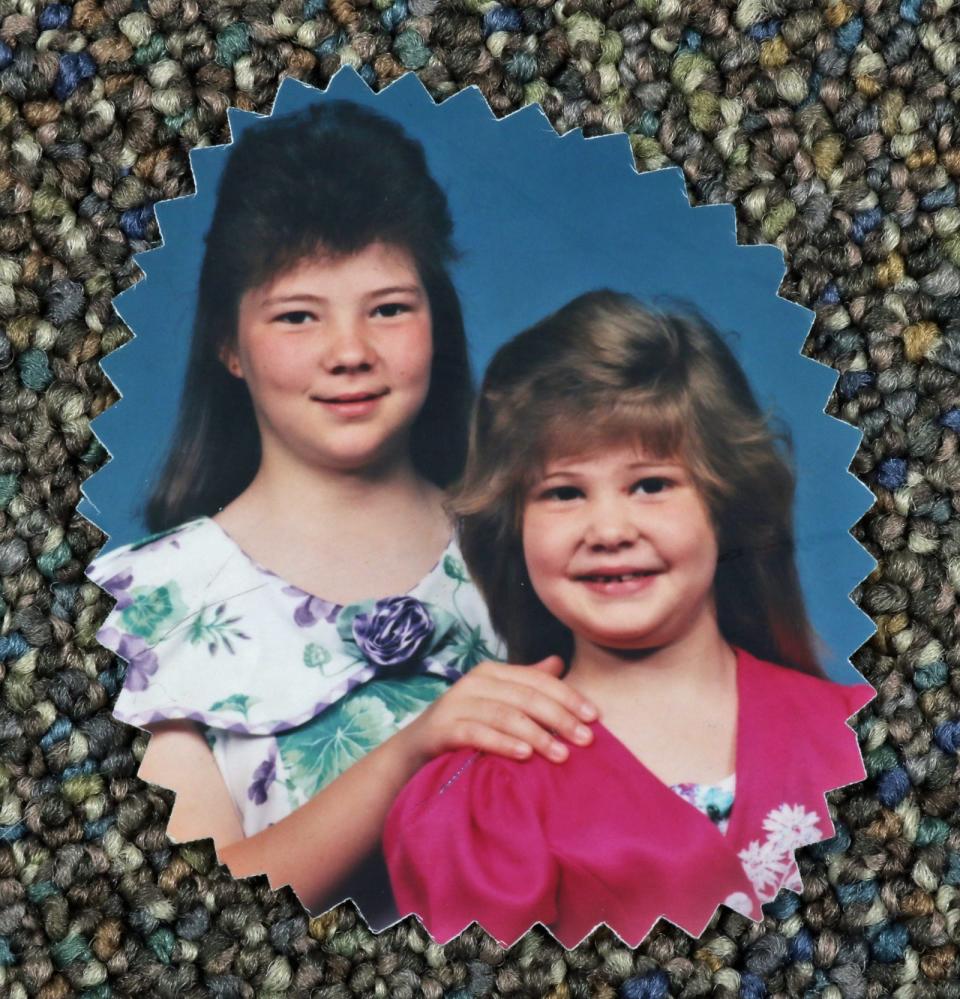

Gaston County sisters die a month apart

Diane Brooks didn't fully realize that her oldest daughter was dead until she heard the hospital chaplain speaking in past tense.

Brooks was at CaroMont Regional Medical Center, with her other daughter, Haley. They had received a Facebook message that Brooks' oldest daughter, Amanda Grigg Whitley, had died, and they were trying to find out whether it was true, Haley said.

"She started talking about her in past tense. And Mom was like, 'you just said was, and she was like, 'I'm so sorry. I thought you just said you knew she was dead,'" she said.

Whitley, who was 37, had died of an apparent drug overdose in a wooded area in Gastonia on Feb. 8. While her death was not a total shock to her family — she had been struggling with addiction for years — she died shortly after her younger sister, 34-year-old Whitney Brooks, who died on Jan. 3 at Atrium Health after just over two weeks of incarceration in the Cleveland County Detention Center.

The two women's lives — and deaths — were closely intertwined.

The two died just over a month apart from one another, and prior to their deaths, both had for years experienced homelessness, a situation spurred by their struggle with addiction. In November, both women were staying at an encampment on North Oakland Street in Gastonia, but the sisters were originally from Bessemer City.

Amanda Grigg Whitley

Amanda was the oldest, born Nov. 13, 1985, at Piedmont Medical Center in Rock Hill, South Carolina. She weighed 8 pounds, 8 ounces.

When Amanda was born, Diane Brooks was 17 and living at a home for single mothers.

She thought about putting Amanda up for adoption, but changed her mind.

"I just couldn't do it," she said.

Amanda was a bright child, her mother said.

"She was A-B honor roll, honors society, very intelligent," she said.

Then, at age 13, she became pregnant. She gave birth to a baby boy, and she gave him up for adoption.

Not long after, in 2002, her biological father, Robin Griffin, died. He was in his 30s.

As a teenager, Amanda dropped out of Bessemer City High School, eventually earning her GED. Then, she met a guy named Dean Haney.

"That was literally the love of her life," Diane said.

He proposed on Valentine's Day in 2004. In the early morning hours of Feb. 16, 2004, he was killed in a car accident at the age of 21.

Amanda's second child, a son she had with Haney, was around 6 months old at the time.

The adoption of her first child and the two deaths that followed marked a turning point for Amanda.

What followed was a lifelong struggle with addiction. She started with pills, using drugs that energized her, and she eventually turned to the syringe, injecting herself with suboxone, a drug that is normally used to treat opiate addiction. At some point, she also began using hard drugs, like methamphetamine.

By her mid-20s, Amanda struggled to keep a home. For years, she cycled on and off the streets and in and out of rehabilitation programs. By 2023, she seemed more comfortable on the streets than off of them, her mother said.

"I spent a great deal of money to get them a motel room, and she was already at the point of being adapted to being homeless," Diane said. "She couldn't stay in a hotel room. She said she felt like the walls were closing in on her."

The last time Diane saw Amanda, however, the dynamic was markedly different.

It was Feb 7., the day before Amanda's death, and Diane went to visit Amanda, who was camped out behind a Dollar General store on Ozark Avenue in Gastonia. Amanda was grieving deeply for Whitney, and when her mother approached, she broke down.

"And usually I don't get out of the car. I got out of the car this time. And she came to me and she just grabbed me and I mean, it's like we had our hug moment and she just bawled," Diane said. "She cried and cried and talked about how much she missed Whitney."

Diane sat with her daughter.

"And she started talking about how she was having dreams lately of her dad, and of Dean and Whitney. And it's like she's seeing him in her dreams," she said.

Amanda told her mother that the last time she heard Whitney's voice, Whitney was getting beaten by a man she was with.

"Whitney and Amanda both were in drug-fueled abusive relationships, I guess. Amanda said that she had broken them up before and she wasn't doing it again," Haley said.

Later, when Amanda went to check on Whitney, Whitney wasn't there. She had been arrested.

"That's when they sent her to Cleveland County," Haley said.

Whitney's death had devastated Amanda. Although the two fought in their younger years, they had become closer as adults. Their lives in some ways had paralleled one another.

Whitney Brooks

Amanda was 3 when Whitney was born on Dec. 15, 1988, almost six weeks early, at 6 pounds, 6 ounces.

Whitney was accident-prone as a child. At a little over a year old, she jumped off her father's lap, hit a window sill, and busted her lip, an injury that required plastic surgery.

She later swallowed a penny, a dime, and a marble, and at a family gathering when she was 3 or 4 she ate mothballs. She also ate birth control pills, and she shoved baloney up her nose.

"She was definitely the wild one. She broke her leg, broke her arm, she used to bring snakes and everything up to the house," Haley said. "I swear she had nine lives, and this one was just her ninth one."

Whitney went to Highland School of Technology, and when she graduated in 2007, she had a full scholarship to Mississippi State University for electrical engineering.

She could also sing.

"They had a talent show when she was in high school. She sang, and she got a standing ovation," Diane said.

But Whitney didn't go to college. Her turning point, her mother said, was less a situation than it was the kind of people she chose to have her in her life.

"She chose men and drugs," Diane said.

Whitney also had bipolar disorder.

"And she thought she could fix stupid," her mother said. "She couldn't. They brought her down to their level."

Like Amanda, Whitney got pregnant as a teenager. Her first child was conceived when she was 16.

By the time she was in her early 20s, she had three children, and her teenage experiments with drugs had turned harder: She started using crack cocaine and eventually turned to methamphetamine.

Whitney also had physical health problems. When she was in her late 20s, she called her mother and asked for help.

"She's like, 'Mom, I went to the doctor. They told me I've got holes in my heart. And if I do not get these valve transplants, I'm going to die,'" Diane said. "In the meantime, she was doing nothing but running and doing drugs."

Diane brought her daughter home, and she had her heart surgery, but within three months, Whitney was back with another man. He was abusive, and she began using methamphetamine again.

"And then we just started noticing things like her stealing, her lying — like, she stole mom's wedding ring. She let a guy she was talking to come in and steal a bunch of Dad's tools," Haley said.

They became worried about Whitney's influence over her own daughter, who Diane was caring for, and Diane made a difficult decision:

"I could not let Whitney stay there doing what she was doing. I had to make a choice again. You know, Whitney had to leave," Diane said.

Tough love

Over time, the relationships Whitney and Amanda both had with their family frayed. They loved them, but they felt they had to love them from a distance.

"Amanda and Whitney, I know they tried," Haley said. "But at the same time, they just hit that point where they were so delusional. They really thought that they were going to do it different."

"We knew they weren't," Diane agreed.

Whitney's relationship with her family was further damaged when, a couple of years ago, Whitney had an encounter with police and told them that her name was Haley Brooks, not Whitney Brooks, then fled from the police and managed to escape.

Police arrested Haley and charged her with Whitney's crimes. The legal snafu was eventually unraveled and Haley's record expunged, but the news of her arrest was posted on Facebook, and she believes she lost at least one job opportunity because of it.

"After a certain extent, we tried to keep our distance from Whitney and Amanda. It was definitely doing us more harm, trying to help," Haley said.

"We loved from a distance," Diane added.

"At this point, they both had been doing it for so long, even speaking to them, they were not the same anymore," Haley added.

Diane said that Whitney's health problems, exacerbated by living on the street, persisted into her 30s. When she was arrested in December, she was not well.

"Whitney was actually trying to clean herself up some. She had been sick. She was trying to get off of some of the drugs she was on," Diane said.

Amanda also had talked about going to treatment. She had spent some time in rehabilitation programs, but the treatments never quite stuck, and she at times would go months without communicating with her family. Still, she had a total of eight children, and she was about to have a grandchild.

"We never gave up full hope that they would actually get clean and stuff, especially since Amanda was about to be a grandma," Haley said. "We thought maybe that would really open her eyes."

Tragedy

It was not to be. And now, with both women dead, their family has been left to pick up the pieces, grappling with the broken lives of each woman and untangling all they left behind.

"No matter what they've done, we still loved them, and we tried to do everything to get them clean," Haley said.

Haley added that watching Whitney in particular die in the hospital after her stay in the Cleveland County Detention Center has angered her.

"I kept my distance from Whitney, especially after the whole identity thing. We didn't have too much to do with each other. But she knew I loved her," she said. "And I know she loved me deep down."

Since her two daughters died, Diane has had her own medical problems, which she feels are a result of her grief.

"I was in the hospital a few weeks ago. They said that my heart on the right side is enlarged, which is specified as a type of broken heart syndrome," she said. "No mother should have to lose two kids in a month. I was used to them being gone, you know, three or four months at a time and doing whatever, but at least I knew they would be back. They would call me, and now, I don't have that anymore."

This article originally appeared on The Gaston Gazette: Gaston County sisters die a month apart