As gay men, we lived with the repression and hostility. We won’t go back there again | Opinion

I was a child in May of 1933, but still big enough to listen to the radio with my parents. I’m sure I didn’t understand the reporting of the book burning in Germany, but I’ve never forgotten that night.

My mother was crying, and my father was trying to comfort her. She seldom cried, so I knew something terrible was happening. But no one, at that time, knew how bad it was going to be. Nor do we now as we watch the books banned in Florida.

Yet isn’t it all too obvious? Ninety years ago, we were watching the first steps in Hitler’s attempt to eradicate Jews. Now we’re seeing the first steps in Gov. DeSantis’ targeting of gays. Why?

At 17, I went to New York to be an actor. I wouldn’t have to listen to innuendo in my small town anymore about Jews or homosexuals, or be bullied at school. I could be who I really was, part of a city of seven and a half million people, all who lived freely — well, almost all.

I soon learned that I had to hide my real self, or agents and casting people would not send me out on jobs. At one point when I finally got my best role on Broadway, the leading lady told me how happy she was that I had been cast. “I was so sure they were going to give me one of those little queers,” she said. I wanted to answer her, but I needed the job too badly. By then I had learned to cloak myself in masculinity.

I had some success, acted with the stars of the time and even became a star on my own in early television. I had a few homosexual friends, but life with them was not only in a closet, but in a closet that didn’t have a lot of light. I wanted to fit into the life around me. I had affairs with women. A marriage of convenience, a long relationship with a beautiful and talented actress. But finally, analysis made me realize that I was truly homosexual, and my life would only be fulfilled if I accepted it. Analysis also gave me another surprise — I didn’t have to be an actor to live a happy life.

Time passed. I went overseas with the USO and discovered some of our best pilots, who were turning the war to our favor, were gay — by then, the word was beginning to be used. They didn’t live openly, but managed a life out of sight. Many of them went on missions with their lovers, which gave then additional courage. As the years went on, gays no longer faced the threat of prison — and even won legal and political battles. I had a great relationship with the artist Norman Sunshine that will reach its 65th year in July. The law allowed us to marry in 2004. We lived openly as a couple, and no one seemed to care.

However, that wasn’t the case in 1976. While I was in the film division at Warner Brothers, they asked me to take over the failing television division for a few months until it could be closed down. I couldn’t just sit around and do nothing, so I soon began selling pilots, doing star-driven dramas and inadvertently put Warners Television back on the map.

The studio heads decided to stay in the business. They came to me for suggestions as to who they could get to take over the division. Not once did anyone mention giving me the job. I suggested myself. They were startled, explaining they were afraid I couldn’t sell shows to the men in the “old boys” TV networks because I was gay. They mulled it over for weeks, and then my phone rang. “Hello, president” they shouted.

For 10 years I shepherded “Alice,” “The Dukes of Hazzard,” “Night Court,” “Growing Pains,” “Head of the Class,” “Scarecrow and Mrs. King,” “Wonder Woman,” “Scruples” and many other shows.

Norman and I effortlessly became part of the Hollywood community. Still, once in a while, we had to put on the brakes.

I had produced “The House Without a Christmas Tree” for CBS. Norman stopped painting and sculpting long enough to create heartbreaking collages for it and the three additional specials I had been asked to do. When he was nominated for an Emmy for his graphic art in 1976, I was advised not to go to the ceremony. We were told, “It will call too much attention to your being a couple!” We both were angry, with each other and the world, when Norman won, and I wasn’t even there.

In a way, Norman got back at everyone by writing about it in 2011 in a New York Times op-ed, “Before the Emmys were gay.” It highlighted his disappointment when he won and couldn’t be with me. By then, the world had progressed even further: Jane Lynch, an out lesbian, hosted the Emmys that year, and gay men who won kissed their husbands or partners in sight of the cameras.

We thought things were getting better and better, with polls showing the majority of Americans approving of gay marriage. But, suddenly, DeSantis appeared, a politician trying to inflame his followers with a campaign that gays’ advocates called “Don’t Say Gay,” to prevent teachers from talking about sexual orientation with children.

A little voice inside my head spoke up: “Everyone, take off the blindfolds. First, they burn the books, then they burn the people.”

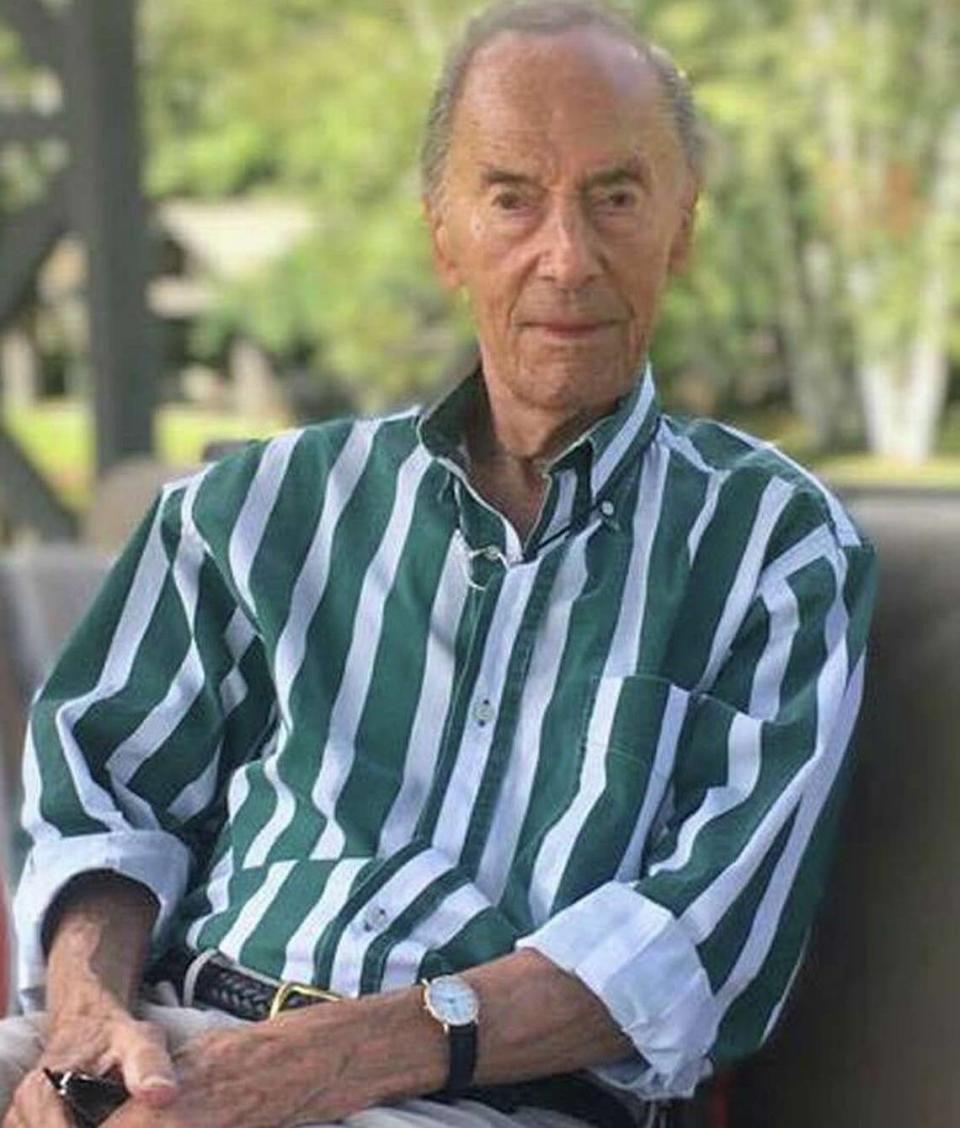

Alan Shayne is the author of “The Star in the Dressing Room: An Actor’s Life. He lives in Palm Beach County.