Gay Yoga Guru Johnson Chong Can Help Sort Out Your Karma and Dharma

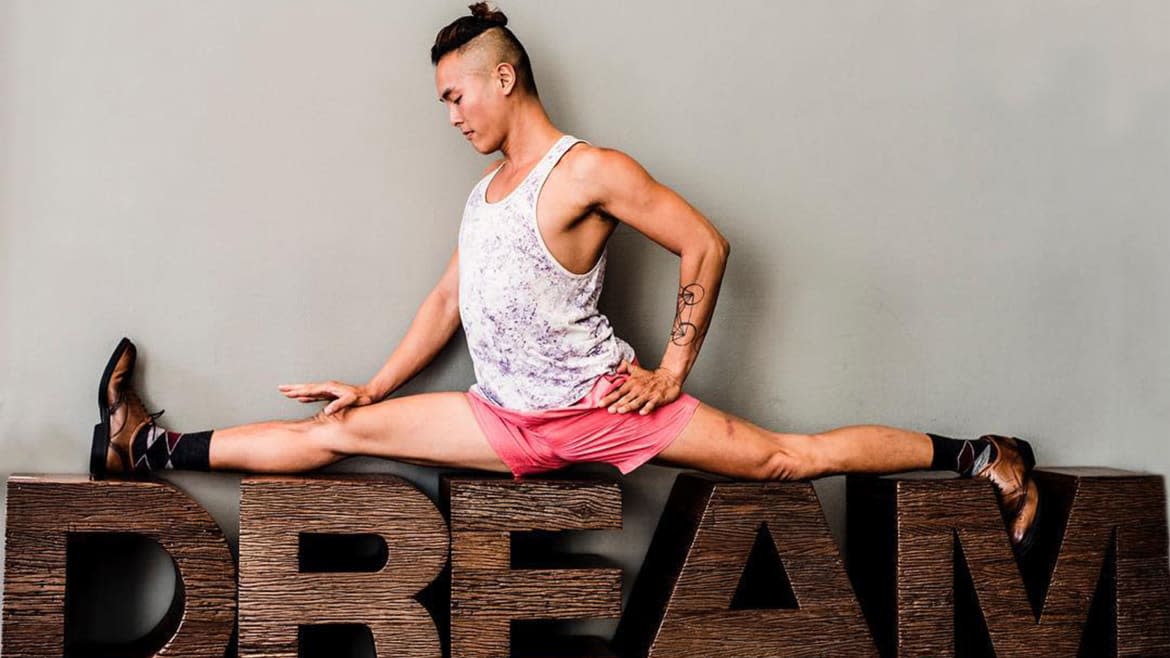

You can judge Johnson Chong’s book by its cover.

It’s pretty clear from its image, of Chong’s face and upper body painted in hues of red, blue, and yellow, that Sage Sapien: From Karma to Dharma is not just another random yoga book.

And sure enough, Chong isn’t another random yoga teacher. Born in New York City to two refugees fleeing persecution in China, Chong is a queer person of color teaching in a predominantly white, straight field. And a self-described “weird gay person.”

Prince Charles Backs Free Yoga To Beat Healthcare Crisis

“People ask me all the time, ‘Who are you?’” Johnson told me over coffee at Union Square’s famous Jivamukti yoga center. “I’m whoever I want to be right now. It’s moving constantly. I play a lot of different roles.”

Sage Sapien traces the development of some of those roles: from a gay kid growing up in a socially conservative, immigrant family to a struggling actor in New York to a successful teacher of yoga and spirituality (currently based in Singapore, but moving to Australia this fall).

“As a teenager, I was very angry and really upset, and I didn't know how I fit into the world,” Chong told me. “How do I fit into this narrative that is America? The only thing that made sense to me was to hate everything and be nihilistic.”

“And then,” he continued, “all of a sudden, I was exposed to spirituality, and I went vegan, and people were like ‘What the hell happened to you?’ So there’s this weird split that happened.”

Chong told me that he knew he was gay at age 4. “I always knew I was gay, but I didn’t know the word,” he said. “When I was young, I remember, I would watch All My Children when my Mom was out, and I would just start doing what Susan Lucci would do: manipulating men, making out with all these hot guys, and I would start mimicking what she was doing. And I was wearing my mom’s bra and high heels and stuff. Most boys do that, right?”

Admittedly, that’s pretty gay.

“But,” Chong continued, “I remember my mom smacking the hell out of me and saying ‘No,’ so I knew that it was wrong. I developed this barometer of what was acceptable and not acceptable to my family at a very young age. I made a pact with myself that I wouldn’t come out to my parents until I was 40, or they were dead.”

That didn’t last.

“As soon as I did all this work, exploring yoga and meditation and so on, all of a sudden at age 26, I was like, ‘Oh wait, I need to not hide anymore.’”

Even today, book, partner, and hot-yoga-bod notwithstanding, Chong told me his parents still don’t accept who he is. His mother recently encouraged Chong to visit a Shaolin monk who, it is said, can help gay people become straight. “A TCM [Traditional Chinese Medicine] version of conversion therapy,” he called it.

“My parents are very non-accepting of me,” Chong said. “They experienced a lot of trauma. They were landowners in China, so in the 1970s, the country labeled them enemies of the state, and rejected them. So there was a big rejection on a macro level. And on a micro level, they've rejected me for I as I am... So you have this karmic cycle of rejection in my family.”

The subtitle of Sage Sapien—from karma to dharma—reflects Chong’s evolution from that familial trauma (karma) to self-actualization and self-empowerment through yoga and meditation (dharma).

It partly happened by chance. Chong left New York largely to get away from his parents—“I thought they would disown me, but instead they became weirdly more caring of me thinking that they could save me”—and when a teacher offered him the opportunity to teach at his yoga ashram in Rishikesh, India, Chong said, “I just dropped everything. I quit everything.”

After six months of teaching in India, Chong was offered a job teaching in Singapore. “And then I met my partner there. It wasn’t expected.”

Having undergone this journey, Chong says he’s written Sage Sapien in part for anyone who finds themselves outside of their society’s boxes and classifications. And yet, after embracing the label of “weird gay person,” Chong quickly qualified what he meant by that.

“I mean, I’m weird and not weird,” he said. “I'm weird to people who don't understand my perspectives—like I'm weird to my parents, because they have a certain outlook on life and they have certain belief systems that they set in place to deal with the extreme violence and trauma and betrayal that they've experienced from their country and their family. So, to people who have very narrow belief systems, I’m weird. But to others who are more fluid and more open, I’m not. It’s not a word I use, but it’s a word I experienced as a young person.”

At the same time, Chong emphasized the universal rather than the particular aspects of his own story. “My story is not unique,” he said. “I think everyone has a pain story, and I think my having the willingness to share my story, others can find the courage to explore theirs.”

“Everyone has wounds,” he continued, “and those wounds will never really go away. It’s about how we use those wounds.”

That’s true for Chong’s queerness as well. “I think there are going to be unique challenges that a gay person or queer person faces that may resonate with someone else who is going through a parallel path. But if you zoom out at the universal themes, it's still going to be a story about abandonment, betrayal, denial, rejection, abuse. These are broad themes.”

My last question, I told Chong, was going to be the hardest. Daily Beast readers are a cynical bunch, I said. And we like it that way. We’re skeptical of self-help and sentimentality. What, I asked, would you say to that reader, given all that you’ve been through?

“You know what?” he replied, “A cynic is meant to be a cynic. The cynic’s role in society is to poke holes at things—and thank goodness for that. Personally, I doubt a lot. You know, I’ll have these big experiences and it’s very emotional, it’s very energetic. I can’t deny what I’ve experienced, but afterwards my mind will try to rationalize it. And that’s the role of the mind: to doubt and to be skeptical. That’s the filter of how we experience consciousness. That’s the beauty of the mind. We just have to be able to make the mind an ally.”

At the end of the day, Chong said, “I think a cynic just needs to know that there are many ways of looking at life. Whether you look at life from a more kaleidoscopic or colorful lens, or you look at it from cold, hard data, there are always other ways.”

Coming from a man who had an actual kaleidoscopic vision painted on his body, that says a lot.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.