With a New Gel, the Future of Male Birth Control Looks Bright

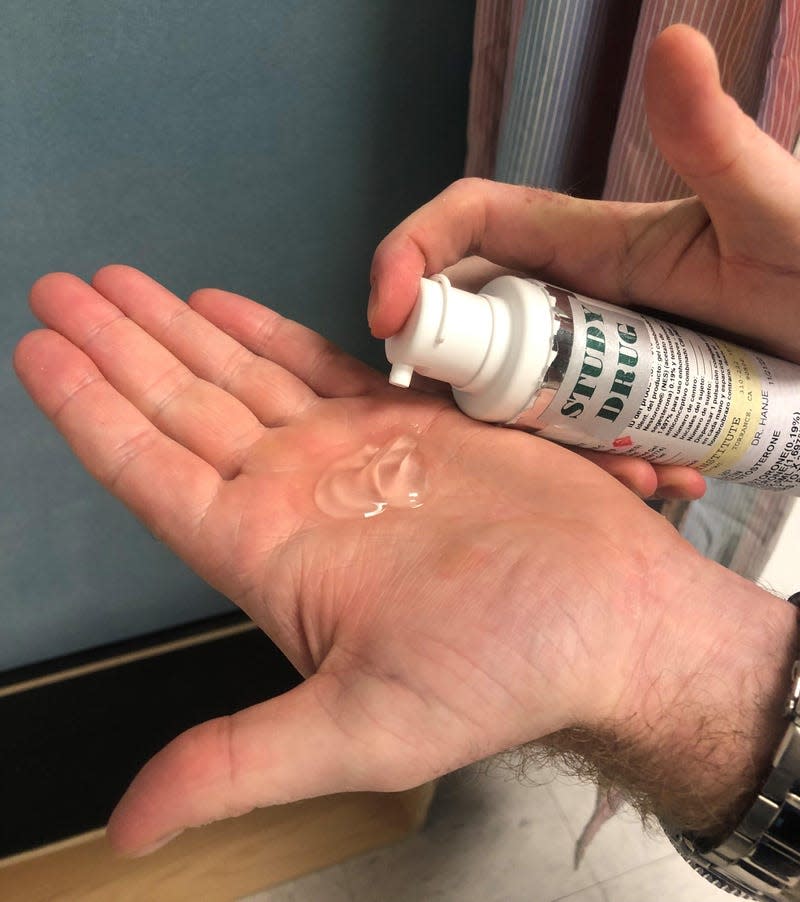

The invention of birth control provided women with a degree of reproductive freedom that past generations never had, and today there is a great variety of options: pills, rings, gels, vaginal sponges, long-acting implants, surgery, and specialized condoms. Men, on the other hand, only have condoms and the surgical, usually permanent option of a vasectomy. But a team of researchers now believes they’re on the brink of bringing the first novel kind of male contraceptive to the public: a topical gel applied once a day to the shoulders. It’s possible that this will only be the start of a new era of male birth control.

The gel, a winner of the 2023 Gizmodo Science Fair, is called NES/T, which is short for the two main ingredients it carries, nestorone and testosterone. Nestorone, also known as segesterone acetate, is a synthetic version of progesterone, a hormone that plays a major role in regulating pregnancy and other reproductive functions. Nestorone and similar drugs are already used as hormonal birth control for women. When it’s given to men, the drug lowers the levels of hormones in the testes responsible for male fertility, including testosterone, which then leads to low sperm counts. The trouble is that it also lowers testosterone circulating in the blood, which can have counterproductive effects like reduced sex drive. So by adding synthetic testosterone to the gel, the theory goes, you can keep levels of the hormone stable in men’s blood, while still ensuring their temporary sterility and minimizing side-effects.

Read more

These Winning Close-Up Photos Show Life That's Often Overlooked

Remembering Enterprise: The Test Shuttle That Never Flew to Space

Nestorone was developed by the Population Council, a nonprofit organization that has focused on reproductive health and HIV/AIDS research, particularly in the developing world. The NES/T gel was created in collaboration with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, among others. They’ve already brought nestorone-based female contraceptives to the market, such as a long-acting vaginal ring approved in the U.S. in 2018. But it’s been a harder road for NES/T—and for male contraceptives in general.

“Things have changed a lot since we first started working on this. The men that come into this study really wanted to take up responsibility.”

There are many reasons why male birth control hasn’t happened yet. While scientists have tried to develop such treatments for decades, there’s been a general lack of interest and funding from pharmaceutical companies, according to Regine Sitruk-Ware, a distinguished scientist at the Population Council and one of the NES/T project coordinators.

“The research on male contraception has really been held together by small groups of researchers. And we’ve never had much support from industry,” Sitruk-Ware told Gizmodo.

A few options have made it as far as later-phase clinical trials but have been linked to many potential side-effects, such as acne, pain, and mood swings, all but ending their prospects of reaching the public. Some people have noted that female contraceptives have their own laundry list of side effects but were still approved decades ago, and have further argued that these failed projects highlight a gap in how we treat women’s reproductive health versus men’s.

It’s true that at least some drugs approved in the 1960s (when the first birth control pill was legalized) wouldn’t pass regulatory muster if they were being tested today. And there are many ways that gender inequality and bias continues to rear its ugly head in medicine. But the situation is more complicated than a simple double standard. In a 2016 study of a hormonal male contraceptive shot, for instance, the overall rate of side effects was much higher than the typical safety profile for female birth control. And ultimately, it was this high risk that compelled an independent panel of scientists to end the study early, not the patients themselves (when asked, a majority of men in the study still wanted to take the shots).

There’s also an important difference in how fertility works in men and women. Hormonal female birth control generally works by convincing the body that it’s pregnant, which is something that our biology is well-equipped to undergo. But hormonal birth control in men works by reducing sperm count, which isn’t supposed to happen normally. Finding a way to reliably, temporarily, and safely turn off these levers in men has just proven harder to do than it has been for women.

That said, some of our perceptions surrounding gender likely have slowed down the development of male birth control, according to Sitruk-Ware. There’s long been a common belief that men don’t want personal responsibility for birth control, she says, and it’s this belief that has at least partially scared pharma companies away from funding research.

“[The pharmaceutical industry] wants to work on fields where they see a high demand and a high return on investment. And for a long time, they didn’t think that men would use it,” she notes.

Even if that attitude might have been true for a majority of men decades ago, it doesn’t seem to be nowadays. A 2017 survey, for instance, found that over 80% of U.S. men report taking at least some role in preventing pregnancy (usually wearing a condom) and that more than half of eligible men would be interested in trying out new male contraceptives if they became available. Surveys in other parts of the world have found similar trends. And in their own clinical research, researchers such as Christina Wang have seen plenty of interest from their male volunteers.

“Things have changed a lot since we first started working on this. The men that come into this study really wanted to take up responsibility,” said Wang, principal investigator and researcher at The Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

Wang and other researchers around the world are now conducting a Phase IIB trial of NES/T, which involves around 400 couples. An interim analysis of the full results is expected later this year, but the early data looks promising. Last summer, the researchers announced that about 100 couples had completed the trial. Among these volunteers, the gel appeared to be safe, tolerable, and possibly even better at preventing pregnancy than female hormonal birth control, which is around 93% effective in the real world.

The Population Council and their collaborators hope that their results will convince the Food and Drug Administration to grant them permission to start a Phase III trial before the formal end of their current study—a decision that would speed the process toward commercialization. But even if that happens, they’ll still need a pharmaceutical partner willing to fund this next phase and take on some of the hefty costs involved in producing and distributing the gel, should it become approved. Sitruk-Ware says that they’ve been in talks with several small companies, and they’re hopeful that they will find that partner.

Should everything work out as expected, the NES/T gel may soon become the first new kind of male contraceptive to reach the public. But it’s hopefully not going to be the last. Some of the NES/T project’s researchers are also working on a hormonal daily birth control pill for men, which has shown good results in small human trials. In early 2023, a NIH-funded team reported its discovery of a short-lasting, on-demand contraceptive that seems to work safely on male mice. And other scientists are developing non-hormonal methods that might be more appealing to some men.

“I think one of the great things about the field of male contraceptive research is that there’s a lot of collaboration. There’s not a lot of competition—probably because there aren’t very many of us,” said Stephanie Page, a researcher at the University of Washington who is working with the NES/T project and also leading a team developing its own pill and injectable form of hormonal male birth control.

“We think there’s a great unmet need,” Page added. “And even if that isn’t hormonal contraception, it’s just about getting something out there so that people can start to think about how to use it and how that might fit in the contraceptive menu for couples.”

There are still years of research and effort ahead, but the future of male contraception looks brighter than it’s ever been.

Read more: A Male Birth Control Gel Is the Field’s Most Promising Option in Years

More from Gizmodo

Sign up for Gizmodo's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.