Gene Frenette: Seeing LeRoy Butler get into Pro Football Hall of Fame was ultimate road trip

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

My newspaper career has taken me on more than 200 road trips to 36 different states, including visits to every NFL stadium, six Super Bowls, four Final Fours, three national championship-deciding football games, the World Series and a Summer Olympics.

Driving back to my Akron hotel the night of Aug. 6 — having attended two Pro Football Hall of Fame celebration parties in Canton, Ohio, for Jaguars tackle Tony Boselli and Green Bay Packers safety LeRoy Butler — it became clear this was a working road trip for the ages.

There’ll never be another one like this. Not in my lifetime.

No matter who wins road games of the teams I cover, it all feels the same from a work standpoint. Arrive the day before the game, maybe go to dinner if time permits, work 10-12 hours the day of the game, leave for home the morning after the game. Win or lose, it’s pretty much the same feeling and routine.

Gene's previous three columns:

Trending up: Defeat aside, Jaguars' pairing of Trevor Lawrence, Travis Etienne should be entertaining

Running up the tab: Boselli's pricey HOF bash, Browns bungle Watson decision, MLB musings, more

Consistent Cooke: Jaguars need more players to do their job as well as punter Logan Cooke

But at someone’s Hall of Fame festivity, especially if your connection to the recipient goes way back, that’s different. That’s what made my second trip to Canton (went for Bob Hayes posthumous HOF induction in 2009) so memorable.

Boselli’s opulent event at a spacious Canton farmhouse property was a gathering of both Jaguars royalty and numerous team employees who were around during his time in black and teal.

It was cool to see so many players from the franchise’s glory years of the 1990s in attendance.

A different kind of celebration

After nearly two hours at the Boselli festivities, I arrived at Gervasi Vineyard wine resort about midway through the Butler party, which had a different feel to it.

Yes, a similar bunch of happy people having a good time, but in a smaller, more intimate setting.

“That’s the party I wanted,” said Butler. “I wanted a small gathering of family, friends and teammates.”

For me, it was a blast from a more distant past, a stroll down memory lane of pre-Jaguars days.

I didn’t even notice all four Hall of Famers at Butler’s celebration: safety Steve Atwater, running back Edgerrin James, guard Jerry Kramer and linebacker Dave Robinson.

They didn't stand out as much to me as watching the unbridled joy of people who were part of his Jacksonville roots.

Seeing Butler’s sister, Vicki, and siblings Michael and Darion, basking in the joy of their kid brother’s milestone was a heartwarming sight.

Wayne Belger, one of his high school coaches from Lee (now Riverside High), drove up with his wife from North Carolina, because he didn’t want to miss a memory that any coach would cherish for the rest of his life.

The same feeling went earlier that day for Butler’s high school defensive coordinator, Leon Barrett, who had to leave for home after attending the HOF ceremony.

It's a shame his high school head coach, Corky Rogers, couldn't be there for this occasion as he passed away in 2020.

Work or no work, a must-see event

It would have been friendship malpractice for me, even if newspaper duties didn’t send me there on a paid work trip to Canton, to not be there for LeRoy’s crowning football achievement.

This celebration party was such a feel-good experience for just the mere improbability of it all.

Nobody figured Butler would reach football’s ultimate destination after such a rough childhood.

Being confined to a wheelchair as a youngster, after surgery corrected a severe pigeon-toed condition, then wearing leg braces that prevented him from playing outside like other kids in his Blodgett Homes project neighborhood.

Those seem like impossible odds to overcome. I didn’t know that LeRoy Butler because we didn’t meet until his sophomore year at Lee High (now Riverside), right after my time covering preps for the defunct Jacksonville Journal was done.

Once or twice a week, since Lee was the closest school to the newspaper offices on Riverside Avenue, I’d go over to their practices and wear out the arms of Lee coaches Gary Warner and Belger by catching passes.

Anybody who played for the Generals in the mid-1980s can attest to this pre-practice ritual.

One day, Butler challenged me to try and catch a pass against him in man-to-man coverage. It was my first attempt, and last, trying to shake a defender with an elite skill set.

A slant route over the middle and a double move down the left sideline had the same result — being blanketed by a future four-time, All-Pro safety who easily broke up well-thrown passes because the intended receiver got zero separation.

Butler was 17 by then, a blue-chip prospect on a steady ascent to stardom at Florida State and later with the Packers. But what stood out to me more than anything was his demeanor, the way he carried himself.

Butler had the right disposition

LeRoy, a linebacker/running back at Lee, was always smiling. You’d never know he grew up in a financially-challenged household or was teased about his physical limitations as a child because he remained relentlessly positive, like he was the luckiest kid on earth.

It’s a trait I would later learn was the direct result of his upbringing from Eunice Butler, his wonderfully polite and engaging single mother.

Whether living in a since torn-down housing project off Jefferson Street, missing his freshman season at FSU as a Prop 48 academic casualty or losing his beloved Eunice to cancer in 2016, Butler never let any type of adversity diminish his optimistic outlook.

He may have felt poor at times from a family income standpoint, but LeRoy was also rich beyond measure because of his family values and the attitude he took with him into adulthood.

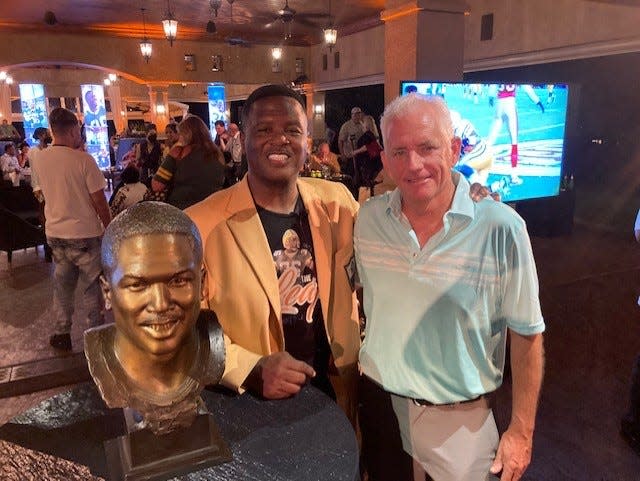

The kid I met as a teenager in the Backyard at Lee and the 54-year-old Hall of Famer who called me up to say a few words at his HOF celebration party was the same guy. Always flashing that trademark smile, forever showing appreciation for friends/teammates and every opportunity he was given.

Always a class act

No matter how small or how long ago, Butler never forgets gestures of kindness. Few people know he was zoned to attend Parker High after playing at Fort Caroline Junior High.

Butler went to Parker for one spring practice, and remembers vividly how helpful the Braves’ star running back, Wayne Gallman (his son, Wayne, Jr. played at Clemson and four seasons with the New York Giants), was to him as a freshman before the Duval County school system forced LeRoy’s transfer to Riverside (Lee) as an ABC student.

Butler didn’t even play organized football until age 12 when his uncle, Charles Von Durham, convinced sister Eunice to let him give it a try in the YMCA league.

LeRoy’s family shelled out $18 for his cleats, uniform and helmet and he played mostly special teams that first year.

With his love for the game, along with the encouraging pep talks his uncle gave him, Butler and football became inseparable.

“I don’t know what it was, but God was always putting me around nice people,” said Butler. “Wayne [Gallman] was the star at Parker and could have acted like he had no time for me, but he didn’t do that. My uncle was at all my practices. He was everything, a male role model. God navigates you through these rough waters of life, but I’ve always had help.

“When you have anxiety and see so much violence in the inner city, you don’t really trust people. But my uncle told me you can’t control [being Black] or poverty. Just put it in God’s hands and be yourself. That made me feel good.”

Over time, Butler’s humility, gratitude and infectious smile made it easy for people to gravitate to him. He makes human connections in such a way that no amount of time or distance can ever really break it.

Our paths continued to cross

As his career ascended, we’d run into each other periodically in postgame FSU locker rooms, the memorable ones being the comeback win over Nebraska at the 1987 Fiesta Bowl and the stunning loss to Southern Miss and quarterback Brett Favre in Jacksonville to begin his 1989 senior year.

We got together at a restaurant in Mobile for the 1990 Senior Bowl. He ordered a non-alcoholic Shirley Temple, standard fare for a Hall of Famer who never drank because he abided by the advice his mother first gave him at age 7 to stay away from alcohol.

Three months later, I was at Eunice’s apartment at Centennial West — not far from the Blodgett Homes projects — to cover the NFL Draft. It was the only time I ever saw LeRoy get rattled.

Midway through the second round, Butler still hadn’t been selected. When unknown Central State cornerback Vince Buck’s name was called out with the 44th overall pick, he got up from his chair and walked outside to calm down.

Nobody could fathom why a first-team, All-America cornerback dropped that far down the draft board, but relief soon arrived when the Packers took him at No. 48. The family gathering erupted in joy, knowing that the kid once confined to a wheelchair and wearing leg braces had made it to football’s highest level.

He would validate Green Bay’s second-round selection by intercepting three passes as a backup cornerback in his rookie season. None of us knew then he’d soon be switched to safety, accelerating a wildly spectacular pro career that ended with 38 interceptions, 20.5 sacks and a Super Bowl ring.

Thirty-two years after that nerve-racking start to his amazing NFL life, Butler received the ultimate football honor.

Seeing him donning a gold jacket on a Canton stage and then relishing every moment of his HOF celebration, all of it was a joyous, exhilarating time.

LeRoy Butler III never forgot where he came from, which is why his inspiring story touches a lot of people.

It was beyond fun to see a good friend reap such a glorious reward.

Gfrenette@jacksonville.com: (904) 359-4540

Gene Frenette Sports columnist at Florida Times-Union, follow him on Twitter @genefrenette

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Butler's football journey to Hall of Fame was a heartwarming reward