The genesis of Memorial Day in RI: Why we remember our fallen heroes

Marion McQuillian was 8½ years old in the spring of 1917. As the accompanying photo shows, she and her classmates at Althea Street Elementary School in Providence were decked out in their Sunday best, carrying American flags.

Marion McQuillian was my mother.

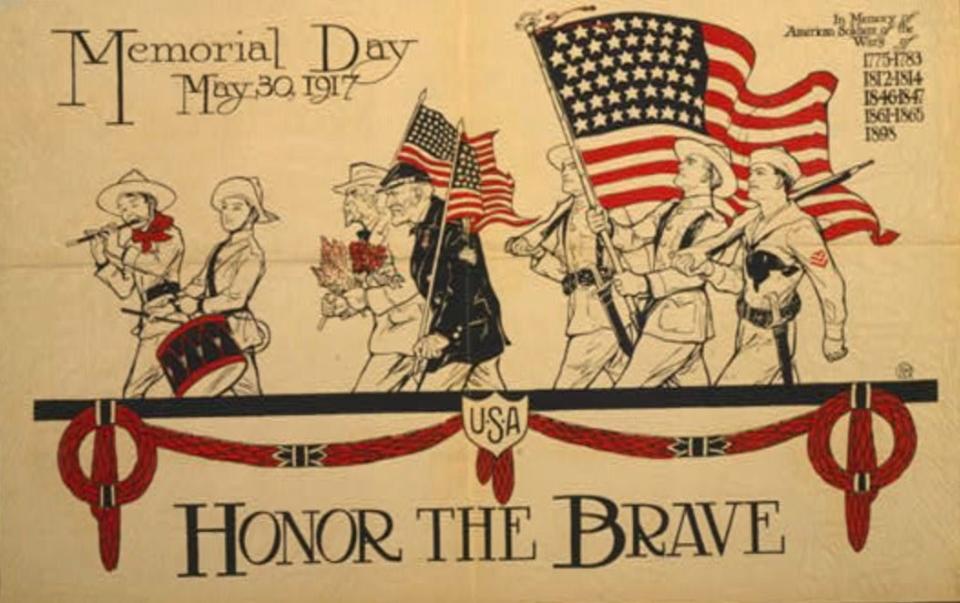

For many days leading up to May 30, The Journal promoted activities for local residents. More than 100 years ago, one could already see the focus shifting from a recognition of our war dead to the launch of summer recreation activities and retail sales.

The Providence Grays were playing a doubleheader at Melrose Park. Hunts Mills, an amusement park in Rumford, offered seven hours of dancing – admission 25 cents, dancing free! The steamer Mount Hope promoted a day trip from Providence to Newport and Block Island.

The May 27 Sunday paper was full of Decoration Day ads. Gladdings promoted white summer shoes. Shepard’s featured khaki suits “for women to show their patriotism on Decoration Day,” plus Brownie cameras to get photos of the festivities.

One could buy a new Chevrolet roadster for $535, so you could “motor on Decoration Day.” (Clearly Memorial Day auto sales are nothing new.)

In spite of the surface exuberance, however, that year was different. On April 6, 1917, the United States had entered World War I, and the prospect of another war and more casualties loomed large.

When Mom gave me the photo later in life, she told me she sensed something different that day, even at her tender age.

Liberty bonds were for sale at Shepard’s. Gladdings was selling miniature flags of all the Allied nations.

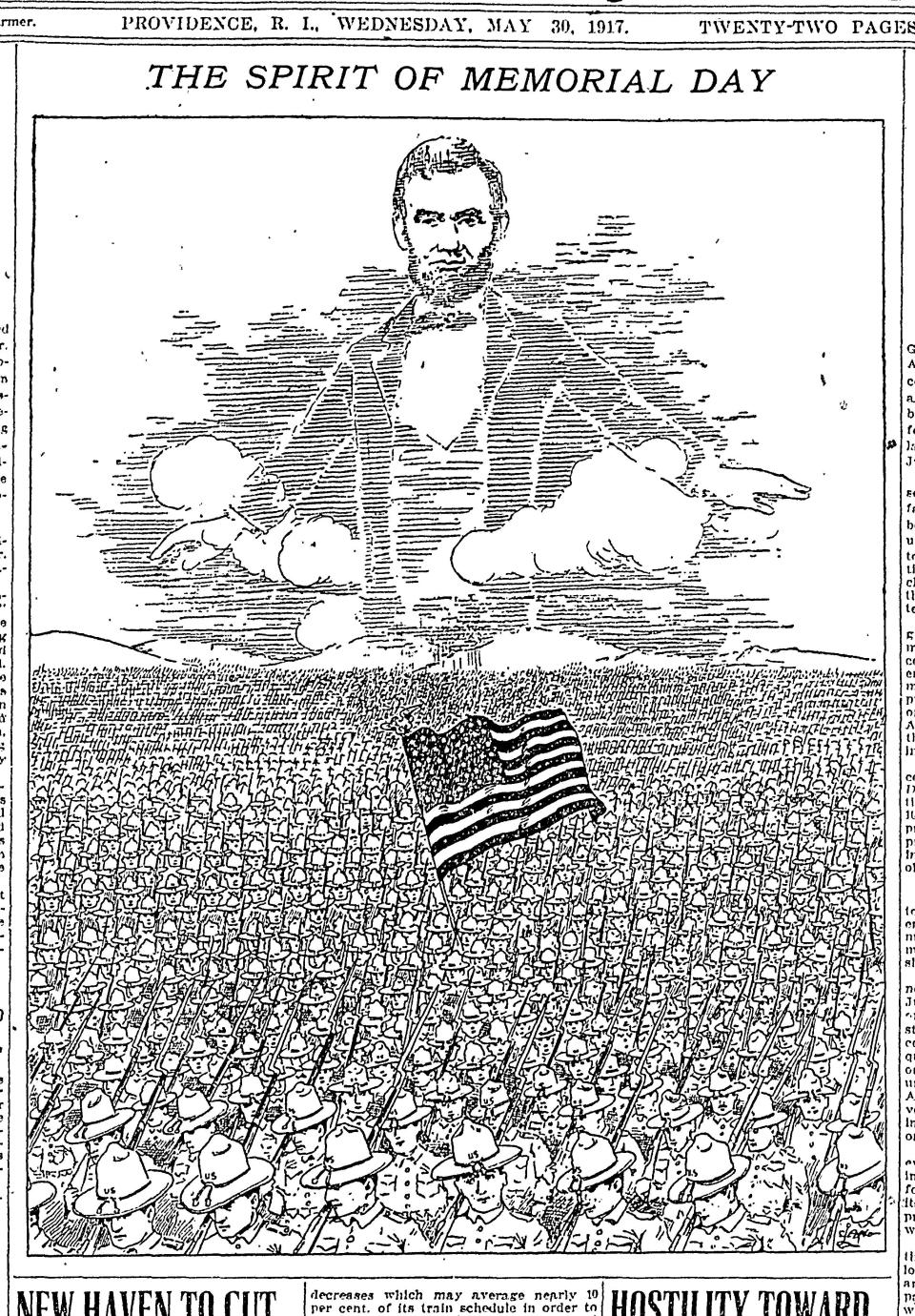

Reports on the parade and ceremonies noted the shift in attitude. A Providence Journal subhead on May 31 read, “Unusual solemnity due to the present war was noticeable.”

The report continued, “Rhode Island Grand Army [Civil War] veterans, accompanied by the soldiers of today, paid their annual tribute to the departed comrades yesterday, participating in the memorial day parade and later decorated the graves of those who have died.”

Flower wagons brought up the rear, and the veterans were transported to local cemeteries, where they placed flowers on the graves of their fallen comrades.

Memorial Day today

Decoration Day is now officially Memorial Day, a day of remembrance for those who have died in U.S. military service.

More than 100,000 American troops died in World War I. Decoration Day was expanded to honor all those who had died while fighting – not just those from the Civil War.

From 1868 to 1970, it was observed on May 30. In 1968, Congress moved four holidays, including Memorial Day, to specified Mondays to create three-day weekends. The law took effect in 1971.

That change was not universally welcomed, especially by veterans. In 2002, the VFW issued this policy statement: “Changing the date merely to create three-day weekends has undermined the very meaning of the day. No doubt, this has contributed a lot to the general public's nonchalant observance of Memorial Day.”

Protestations about changing Veterans Day from Nov. 11 gained more traction, perhaps because the date marked a specific event – the Armistice ending World War I. After a few years, the observance of Veterans Day returned to its Nov. 11 date.

Genesis of Memorial Day

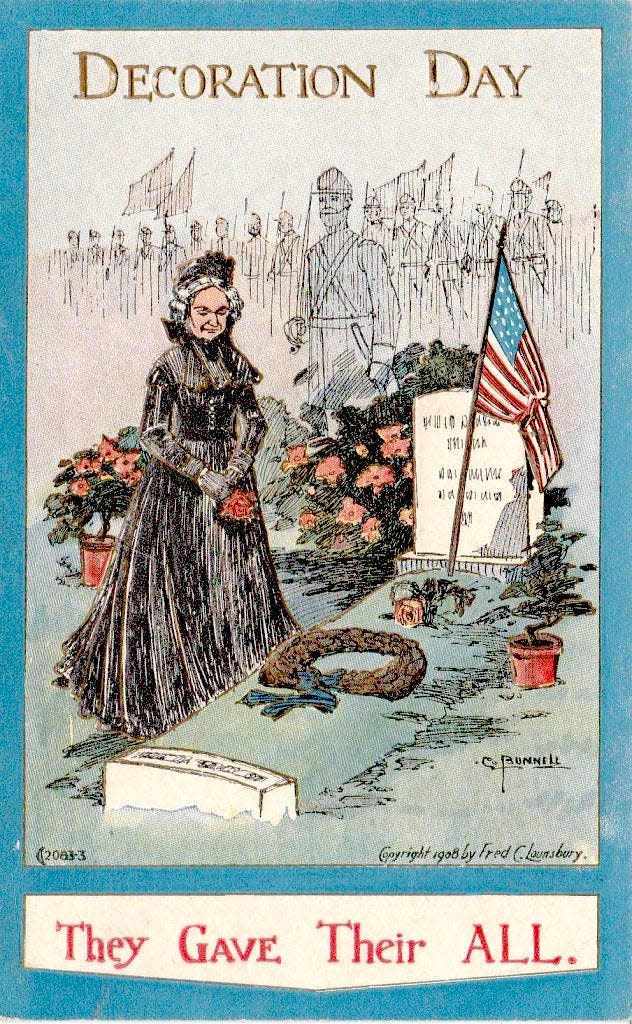

Decorating the graves of fallen heroes goes back before the start of recorded history. In our country, most historians agree the custom dates back to 1866, when women in the South began decorating the graves of war dead from both sides.

Some 700,000 soldiers, Union and Confederate, died in the Civil War from 1861 to 1865. To put that number in context, it is greater than the total number of American war deaths in all other wars in our history combined.

Celebrating Memorial Day on a national scale evolved from an 1868 order delivered by Gen. John Logan, the commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, the Union veterans of the Civil War.

“The 30th of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers, or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet churchyard in the land,” he proclaimed.

Logan acknowledged the idea was not his; he was imitating a practice that began in the South some two years earlier.

In 2012 the New York Times, citing Veterans Administration data, reported that roughly two dozen places claim to have originated Memorial Day. While Waterloo, New York, was officially declared the birthplace of Memorial Day by President Lyndon Johnson in May 1966, most historians disagree.

The 1860s

The spring/summer 2018 Journal of America’s Military Past examined the history of Memorial Day in detail. It found several 1868 articles in Northern newspapers commenting on Logan’s call. All attributed the idea of Memorial Day to women in the South.

As an example, the May 11 Boston Daily Advertiser editorialized, “This custom thus inaugurated is one that was started at the South soon after the close of the war, but is worthy of adoption at the North.”

The New York Times of June 5, 1868, flatly stated, “The ladies of the South instituted this memorial day.”

Even more compelling is the fact that many of these same newspapers reported the April 1866 launch of this effort in Columbus, Georgia, and elsewhere in the former Confederacy.

In Fremont, Ohio, the commentary was specific: “The ladies of Columbus, Georgia, recommended that the 26th of April, each year, be set apart for honoring the Confederate dead, either by pronouncing eulogies upon them, or by adorning their graves.”

In Providence, the Evening Press of April 13, 1866, also printed the news of the impending commemoration.

During those inaugural Southern observances, many participants graciously honored the graves of both Confederate and Union soldiers.

In 1868, memorial events were held in 183 cemeteries in 27 states. The following year, the number of cemeteries nearly doubled, to 363 in 31 states.

While The Providence Journal gave extensive coverage to the activities of 1868, it did not call the holiday by any particular name. The earliest mention I could find in the newspaper archives that specifically referenced “Memorial Day” or “Decoration Day” was dated April 12, 1869.

Interestingly, Wikipedia reports that the name “Memorial Day” did not really come into vogue until about 1882. But the Journal column dated May 18, 1869, was entitled “The National Memorial Day.”

News coverage was extensive, especially in those early years, and the language used by reporters to describe the activities was flowery and effusive.

For example, “Let us as Rhode Islanders, who are ever jealous for the memory of our dead, see to it that the mounds of our martyred comrades, on the coming memorial day are decorated in a manner that shall testify our love and admiration for those who sleep beneath them.

“… Let us keep green and fresh the recollections of those brave departed ones whose last resting places we propose to twine with flowers.”

The true essence of Memorial Day

Richard Gardiner of Columbus State University, in Georgia, is an expert on Memorial Day history. One of his favorite stories is about 12-year-old Jennie Vernon, whose father had died in captivity at Andersonville Prison in Georgia. She lived in Lafayette, Indiana, site of a Union prison. Confederates who died there were buried in a local cemetery.

For the first commemoration in 1868, Jennie made a wreath and delivered it to the cemetery with a note saying, “Will you please put this wreath upon some rebel soldier’s grave? My dear papa is buried at Andersonville, and perhaps some little girl there will be kind enough to put a few flowers upon his grave.”

Word of that gesture spread nationwide, and it stands today as the true essence of Memorial Day.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Memorial Day in RI: How holiday has changed through the years