How genomic testing can personalize treatment for 150K Michiganders offered free kits

Rosalind Brown had blood clots in her lungs.

For years, her doctors tried to get the dose of a blood thinner just right to prevent the risk of a heart attack or other life-threatening complications associated with pulmonary embolisms, but they never found the ideal balance for Brown.

"I couldn't control it," said Brown, 65, of Flint, who was prescribed an anticoagulant drug called warfarin, also known by the brand names Coumadin or Jantoven. "I would go back and forth, back and forth. It was up the dose, lower the dose, then up the dose again. I was going every other day to get my blood checked."

In the summer of 2022, Brown got a letter in the mail from her health insurance company offering a free pharmacogenomic test created by the Minneapolis-based company OneOme that would help her doctors to personalize her treatment based on her genotype.

"I thought this might help," she said, not only to manage the blood clots, but also to treat her other chronic conditions — asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia.

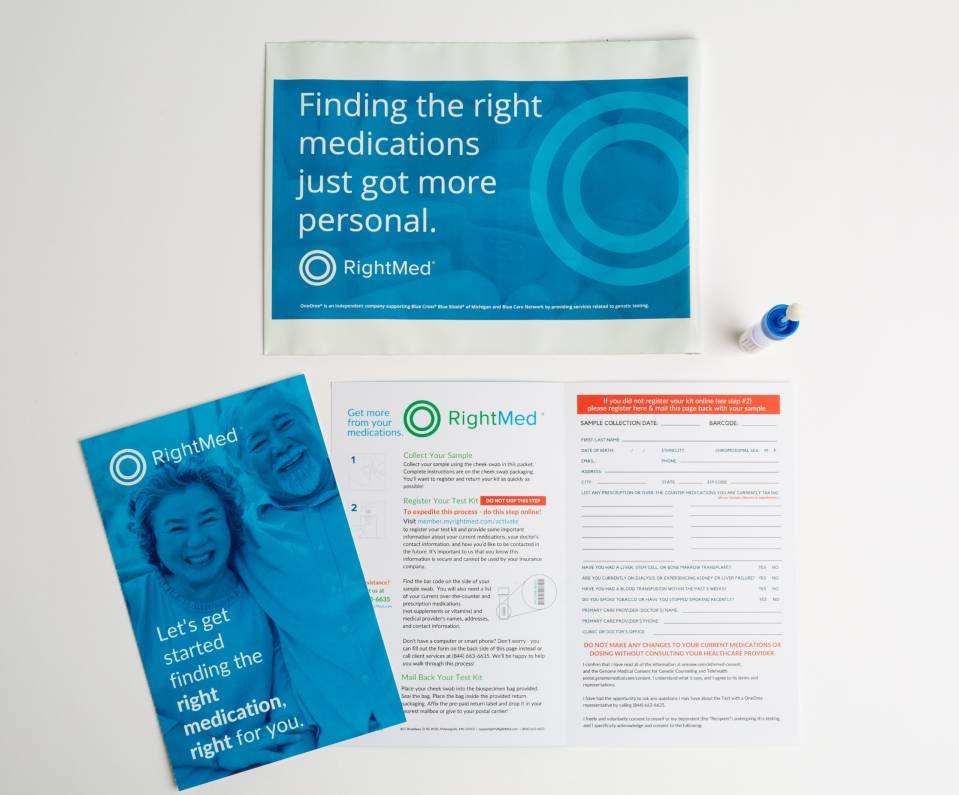

Soon after, Brown used a swab from the RightMed test kit OneOme mailed to her home. She collected a saliva sample, sent it back, and became among the first 500 people in Michigan to undergo pharmacogenomic testing through a pilot program offered to certain members of Blue Care Network's commercial HMO and Medicare Advantage plans.

It's the company's effort to assess how well personalized medicine could work for 150,000 members in Michigan who are most likely to benefit from the tailored treatments.

Genetic analysis looks for 'common genetic variants'

Dr. Scott Betzelos, vice president of HMO strategy and affordability for Blue Care Network, explained that some prescription drugs simply aren't effective for certain people, and the reason might be differences in their genotype.

"Your genes produce proteins, enzymes that metabolize medications," he said. "Either you produce a lot of those enzymes, which means you're a high metabolizer of a particular medication and would need a higher dose, or you're a low metabolizer of a medication and would need a lower dose of the medication, or you're a non-metabolizer, which means that you probably need a different drug altogether."

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified 27 genetic variants associated with interactions involving more than 100 drugs. The RightMed test analyzes more than 100 alleles, which are the matching sets of genes on each chromosome — one inherited from a person's mother and the other from a person's father. Variations in the alleles' coding combinations create the unique genetic sequence that can influence everything from the color of a person's eyes to how a person responds to certain drug treatments.

"Over 90% of the population has a gene variant that may affect a medication that they're taking, whether they're able to effectively metabolize it correctly or not," said Patrick McIntyre, CEO of OneOme, which was co-founded by the Mayo Clinic. "So we're not looking for a needle in a haystack. These are common genetic variants for most Americans."

Interactions 'could be quite severe'

For people undergoing treatment for cancer, cardiovascular disease, mental health disorders and gastrointestinal conditions, pharmacogenomics can play an important role in finding the best treatments, said Atheer Kaddis, vice president of pharmacy services and chief pharmacy officer at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network.

"Blood thinners have a lot of these gene-drug interactions," Kaddis said, "and those could be pretty serious. For example, if there's a patient on a blood thinner, and the blood thinner is not working in the body because of a gene-drug interaction or the patient is not on the right dose of an anticoagulant, that could result in clots, heart attack, stroke or major issues like that."

"So some of these gene-drug interactions could be quite severe if we're not identifying them and if the physician is not intervening to make sure the patient is on the right therapy based on the results of the test," Kaddis said.

Other examples:

Omeprazole and lansoprazole, sold under the brand names Prilosec and Prevacid, are often used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori infections. But they do not work as well in people with certain variants of the CYP2C19 gene.

Fosphenytoin, sold under the brand name Cerebyx, is used to treat epilepsy and prevent seizures. But for people with particular alleles on the CYP2C9 and HLA-B genes, it can cause severe adverse reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, which affects the skin and mucous membranes, causing blistering and rash.

People who take the prescription anticoagulant clopidogrel, also known by the brand name Plavix, and who also have particular variants of the CYP2C19 gene might find the drug doesn't work for them at all. "Plavix is one of those drugs that unless you have the enzyme to break down the medication, you can take it all you want, it's not going to work," Betzelos said.

People with certain variants of the CYP2D6 gene are what the FDA considers "ultrarapid metabolizers" of the pain medication codeine, which the agency warns: "Results in higher systemic active metabolite concentrations and higher adverse reaction risk (life-threatening respiratory depression and death)."

Antidepressants such as as paroxetine (Paxil) and fluvoxamine (Luvox) can be less effective in people with particular variations in the CYP2D6 gene.

'It has helped me more than any other thing did'

Pharmacogenomic testing made all the difference for Brown.

She and her doctor learned that she had genetic variants that affect how well her body metabolizes warfarin. She switched to a different blood thinner called apixaban, which is sold under the brand name Eliquis, and she's doing much better.

"Eliquis is something I never thought about taking. My doctor never thought about putting me on it," she said, before they got the results of her RightMed test. But now, Eliquis is controlling the levels of clotting factors in her blood so well, she only has to go to the lab for blood tests quarterly, rather than every other day.

Brown also was able to change the prescription drugs she uses to treat fibromyalgia.

"My doctor was reading ... the report and what my DNA was showing, and he said, 'Well, according to this, if you're taking hydroxychloroquine and add Cymbalta to it, you should get some relief. Maybe not total relief, but some relief.' He said, 'Are you willing to try it?'

"It has helped me more than any other thing did," Brown said. "I'm taking Cymbalta and hydroxychloroquine every day, and I have better days than I've ever had before."

In the past, cold winter weather brought with it immobilizing pain.

"I could hardly move," said Brown, who retired on disability in 2014 from her job as an unemployment claims examiner for the state of Michigan. "I could never leave the house. Now, I can take this medicine, put on warm clothes and go out for a little while and actually enjoy myself."

Testing offered to 150,000 Michiganders

That kind of outcome is the promise of pharmacogenomic testing, Kaddis said, especially as the science continues to advance.

"We're on the forefront of this now," he said. "We're going to see more of this in the future and more adaption of precision medicine in the future."

So far, free testing has been offered to 150,000 Blue Care Network members in Michigan who have pharmacy benefits through the plan. About 3%-5% of those who've been invited have followed through by submitting test kits — that's between 4,500 and 7,500 people, Betzelos said.

"As a physician, I would love to have more people joining the program," he said. "But you know, there's a number of reasons people are hesitant to take the test. The first being it's genetic testing, and no matter what you say, people are apprehensive about it."

But people also are wary of new things they don't understand, Betzelos said.

"People aren't familiar with it and may not be familiar with pharmacogenomics. Some people want to talk with their physicians about it. This is an opportunity for the entire medical community to continue to enhance their knowledge around pharmacogenomics," he said.

So far, the Blue Care Network plan members who have tried the RightMed tests are seeing the benefits, Kaddis said.

"When the physician actually gets the test results back from OneOme that shows there's a gene-drug interaction for their patient — let's say it shows that Plavix is not working or won't work in the patient — almost 80% of the time, the physician is switching the therapy to a drug that will work for the patient," Kaddis said.

"We still need to educate our physician providers and patients about the value of genetic testing, and we should see an increase in the adoption rate of the test because there'll be more familiarity with it over time. This has significant potential to impact quality of care for patients."

How eligibility is determined

The results of the OneOme pharmacogenomic tests are sent directly to patients and their physicians. Blue Care Network never sees them, Betzelos said.

"We don't get the results, and your employer doesn't get the results," he said, adding that insurance coverage decisions are not affected by the outcome of RightMed testing.

Not all Blue Care Network members in Michigan are eligible for the program, Betzelos said. Members are selected through a stratification process managed by OneOme.

"We send a file to OneOme, which does an artificial intelligence review ... looking for particular drugs that have known FDA gene-drug interactions," Betzelos said. "If it is identified that you are taking one of those drugs, then you have the potential for a gene-drug interaction. ... OneOme then invites those who qualify to join the program.

"The cost to the member and the employer is zero. Our network is underwriting the cost."

Since it launched in 2022, the program has shown "favorable medical and drug cost reductions" for Blue Care Network, Betzelos said, though he didn't detail how much money was saved.

There are no plans, however, to expand the program to include members of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan's PPO insurance plans, Betzelos said, or offer it to all Blue Care Network HMO members.

Those without coverage can purchase a test kit on OneOme's website, which lists the price as $449.

More: Amazon, Costco jump into virtual health care marketplace — but dangers lurk

More: Companies don't have to report health data breaches in Michigan; AG Nessel wants change

Dr. Julie England, senior medical director for OneOme, said that even though more than 90% of the U.S. population has genetic variations that could affect how they respond to prescription drugs, it makes sense to target pharmacogenomic testing first at people who currently take the medicines associated with gene interactions.

"That's the population health way to look at it," England said. "Who can benefit most today? Not all medications have a pharmacogenomics indication. ... But we can apply this in the mental health sector with depression and anxiety drugs. It can be used to help pain management. It can be used in oncology. It can be used in what we call polypharmacy based on what medications the patient is on today, or will be on in the future. Then we can apply it in the appropriate way."

She hopes more people who are eligible for free testing through the Blue Care Network pilot program will take advantage of it.

"There's a lot of people who are eligible for this to be paid for through Blue Cross who have not responded yet," England said. "If they get a letter about it or an email, I would just encourage them to take a look. ... There's a lot of people on the list that that we believe would benefit from the test."

Contact Kristen Shamus: kshamus@freepress.com Subscribe to the Free Press.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Free genomic testing offered to 150K Michiganders