George Mackie, artist and book designer who had won a DFC as a wartime Stirling bomber pilot – obituary

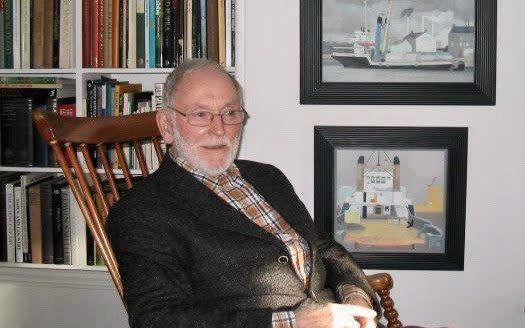

George Mackie, who has died aged 100, became a celebrated book designer and illustrator after the Second World War, during which he served as a pilot with Bomber Command – an experience which left him with mixed feelings.

The middle years of the last century were a golden age in the quality of book production, but all that changed in the late 1960s and 1970s, when letterpress printing all but disappeared and the oil price crisis hit the British paper industry.

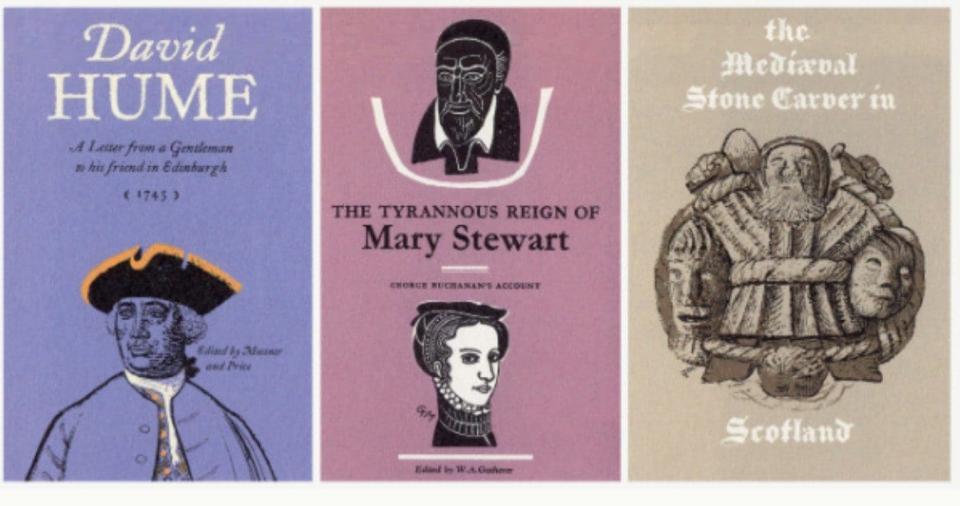

One university press refused to give way, and maintained the standards that others abandoned. This was the Edinburgh University Press, under the direction, from 1953 to 1987, of Archie Turnbull, together with his “official designer” Mackie, whom he had recruited soon after he left art school, on a freelance basis.

Through the 34 years of their creative partnership – supported by excellent local printers, bookbinders and paper-mills – Turnbull and Mackie, working hand-in-glove, continued to design books made using hand-set and machine-composed letterpress type.

Together they studied examples of fine printing and book jackets from the past, and applied them to their designs. Mackie would be given a host of ideas, from which a rough design would emerge, to be debated with Turnbull often over several days.

In letterpress printing, layouts have to be imagined, sketched and minutely specified before pages can be made – an expensive process rendered practical by the precision of Mackie’s layouts.

The quality of Edinburgh University Press publications came to be recognised all over the world. It joined the American Association of University Presses in 1967 and featured regularly in its annual Best Books Show.

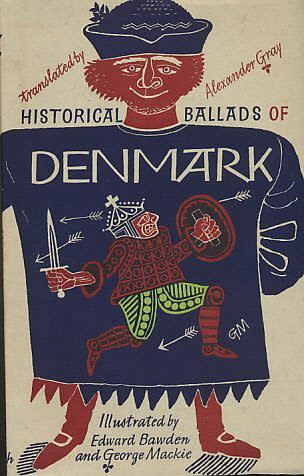

Books designed by Mackie are now collector’s items in themselves, one of the most attractive being Sir Alexander Gray’s translation of Historical Ballads of Denmark (1958), with illustrations by Mackie and Edward Bawden, a limited edition of 750 copies printed on coloured paper.

By the time Turnbull retired and Mackie’s connection with the publisher ended in the 1980s, there was a staff of more than a dozen and 459 titles had been published.

Mackie achieved the rare distinction of being both a Royal Designer for Industry and a recipient of the DFC.

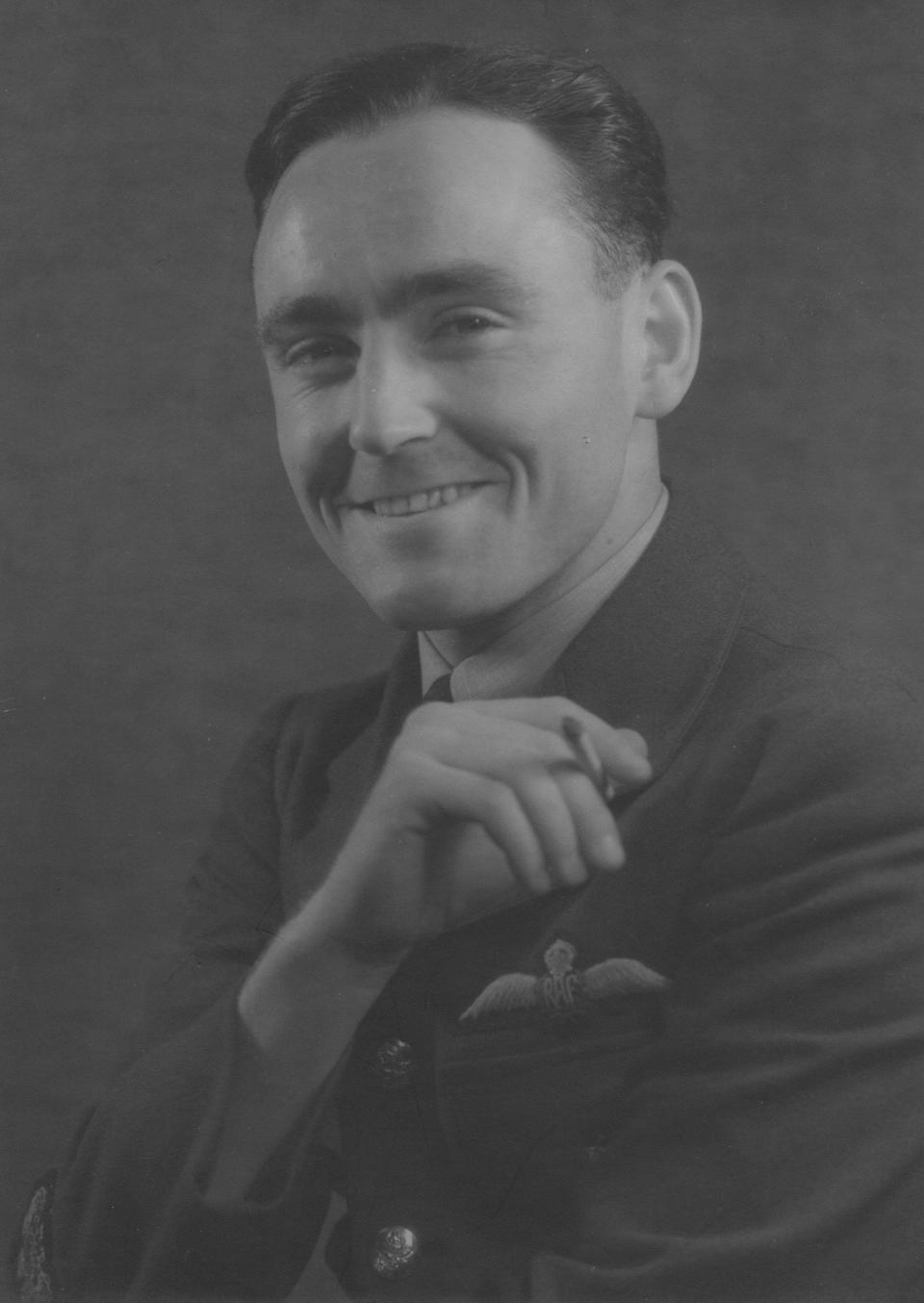

He had joined the RAF aged 19 in July 1940. After training as a pilot, he initially flew Wellington bombers, but in June 1941 he arrived at RAF Wyton, near Huntingdon, to join 15 Squadron, which had recently been re-equipped with the Stirling, the RAF’s first four-engine heavy bomber.

The seven-man crew included two pilots and Mackie flew his first bombing operations as a second pilot before he was given command of his own crew.

Later in 1941, Lady MacRobert, the widow of a Scottish landowner and cattle breeder, made a donation of £25,000 to buy a bomber in memory of her three sons who had all been killed serving in the RAF.

When she presented the Stirling – named “MacRobert’s Reply” – to 15 Squadron she included a letter in which she wrote: “I know you will always strike hard, sharp and straight to the mark. That is the language the enemy understands. My thoughts and thousands of other mothers are with you.”

Mackie bombed industrial targets in Germany, and in December 1941 attacked the German capital ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in Brest. He also dropped mines in approaches to enemy-held ports and in the Baltic. In the eight months he was at RAF Wyton, 20 Stirlings were lost on operations.

In February 1942 Mackie joined a bomber training unit instructing new crews to fly the Stirling, a job some thought was more hazardous than flying on operations. Occasionally, the training units were used to supplement the main bomber squadrons and Mackie flew with a student crew on the first “Thousand Bomber” raid, when the target was Cologne on the night of May 30/31 1942.

Two months later, again with a student crew, he took off to bomb Hamburg. Of the eight crews sent on the operation, four were lost. The weather was atrocious and Mackie was forced to fly in cloud for more than five hours with ice building up on the aircraft’s rudders, ailerons and elevators. He remembered it as his most frightening experience.

In October 1943 Mackie returned to operations to fly the Stirling with 214 Squadron, which soon re-equipped with the American-built B-17 Flying Fortress bomber. A fellow pilot on the squadron, who became a close friend, described Mackie as “a small dark-haired Scot of serious mien and fiery temper”.

He went on to say: “When I got to know him better, I found a tremendous store of humour and warmth that lay in him below the surface.” He also commented that Mackie was recognised as a first-class pilot who “maintained an iron discipline in the air”.

The squadron’s task was to fly radio and radar countermeasure sorties to confuse the enemy’s air defence control and reporting system during major bombing raids.

By October 1944, Mackie had flown 44 operations against the enemy, and later in the year he was awarded the DFC.

Many years after the end of hostilities, Mackie reflected: “I gave the war little thought for many years. With months of service in the frontline, I didn’t see a single dead body. Nor was I aware of the enormity of Europe’s tragedy. I looked down on the burning cities and saw them, with their defences, only as threats to my own survival.”

His ambivalence was reflected in a 2012 letter he wrote to the London Review of Books following an article by Jonathan Meades describing the new Bomber Command Memorial in Green Park as “a lump of Croesus bling”.

“As one who had the audacity to respond in kind to Germany’s bombing campaigns,” Mackie explained, “I write to applaud Jonathan Meades’s demolition of the recently built monument to Bomber Command, which I find trivial and irrelevant.

“The long absence after the war of any formal recognition in stone was creating an increasingly powerful silence where all manner of feelings of revulsion or acclaim were felt. No solid memorial could express so clearly today’s ambivalence.”

George Alexander Mackie was born at Cupar in Fife on July 17 1920 to David Mackie and Kathleen, née Grantham. He was educated at Bell Baxter Secondary School and then at the Dundee College of Art.

After his active service with 214 Squadron he returned to instructing on the Stirling before joining 46 Squadron in February 1945. He was flying a later version of the aircraft, which had been modified as a transport aircraft, and he flew routes that took him as far afield as south-east Asia.

By the end of the war he had completed a total of 2,151.5 hours’ flying. He left the RAF as a flight lieutenant in 1946 to resume his art studies at Edinburgh College of Art.

While working with Edinburgh University Press, Mackie taught design at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen, serving as head of department from 1958 to 1980 .

As well as his books and design work, he was a proficient painter and was elected to the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour. Examples of his works are held in public and private collections. A major retrospective of his book design work was held in 1991 at the National Library of Scotland.

He married, in 1952, his fellow artist Barbara Balmer, RSA, who died in 2017. They had two daughters, one of whom died in March this year.

George Mackie, born July 17 1920, died October 3 2020