George Packer: Americans Don’t Know How to Listen to Each Other

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As we emerge from our COVID cocoons, after all the endless hours spent doomscrolling and anguishing, despite having a new administration, it sometimes feels like not much has really changed. We’re still fiercely divided, as we have been since the 21st century began. Even out of office, Donald Trump stokes the xenophobic right’s passionate intensity while the left lacks all conviction on how to use their meager legislative edge. Maybe we’ve all fallen in love with the drama, gleefully living out our vicarious political grudges within the anonymity of cyberspace. It’s high time to take some sober stock of the state of the nation.

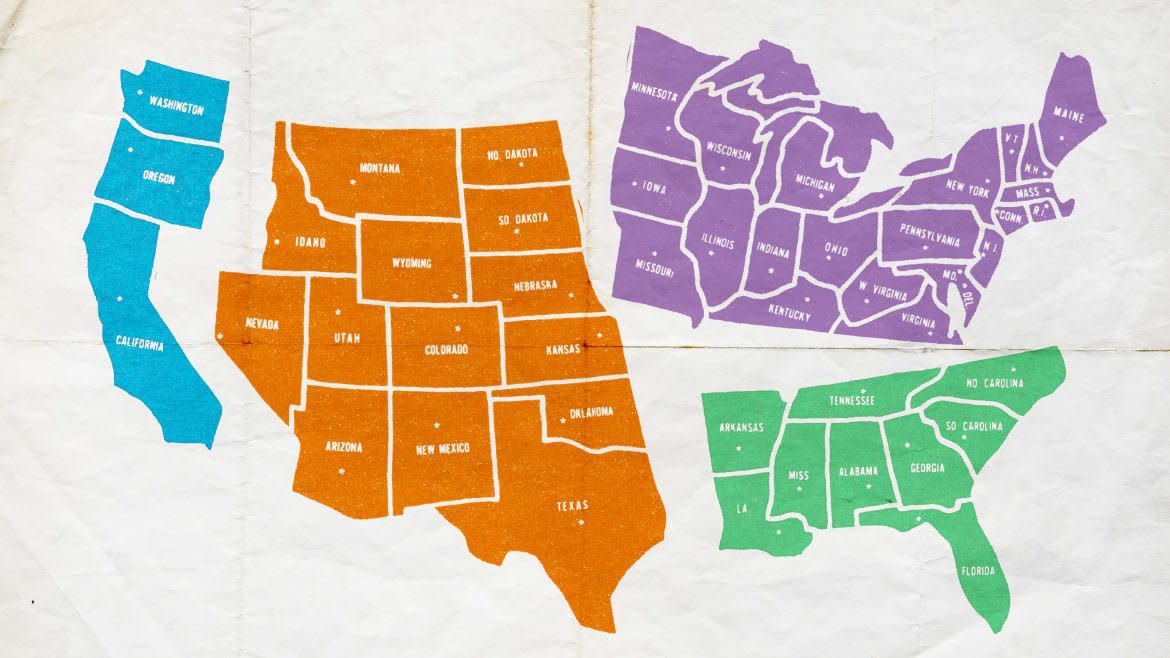

George Packer is a journalist as well as a fiction writer, and these two disciplines inform how he interprets America. Instead of just crunching numbers or mounting a soapbox, Packer analyzes the country’s disparate narratives and forensically inspects their roots and contradictions. His most recent nonfiction, Last Best Hope, was inspired by the extended political essays of Orwell and Whitman with a subtitle that aims to address “America in crisis and renewal.” Packer attempts to outline the different contours of American political life, which he calls “the four Americas.”

How Public Squares Disrupt City Life and Why That’s a Good Thing

First, there’s what he calls “Free America,” which relentlessly pushes for every form of deregulation, valorizes the free market, and enjoys massive tax cuts benefiting corporations. Free America’s hero is the avuncular Ronald Reagan, who regularly let Wall Street greedheads and corporate raiders get away with financial larceny while genially explaining that the scariest words in the world were, “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.” Reagan’s administration didn’t care very much about overbearing government when it suited their various unconstitutional agendas, but that’s another story.

Free America has developed an unlikely political ally in “Real America,” which is depicted in a million soft-focus political ads touting the simple joys of rural and small-town American life, with its fetishizing of piety, hard work, common sense, and family values. Packer, somewhat misguidedly, puts Sarah Palin as Real America’s avatar. This certainly seemed true for a time but Palin’s quick slide from VP candidate to reality TV star only emphasizes how much of a charade her “hockey mom” persona was all along. And her creepy clones (Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert, etc.) throw the ostensible wholesomeness of Real America, plagued with paranoia, scapegoating, and addiction, into serious question.

On the center-left side of the spectrum, there’s “Smart America,” the meritocratic, Ivy League, globalized, data- and tech-obsessed, urban professional elite. These are the Boomer types who are all for socially liberal causes but who don’t particularly want the inconvenience or sacrifice real social change requires. Bill Clinton, the Rhodes scholar from Arkansas, won two elections by appealing to building a “bridge to the 21st century.” Clintonism was boosted by the internet boom (which Al Gore wisely funded early) and borrowed policy from the right while sweet-talking the left, thus triangulating his way to victory during the so-called “end of history.”

Further to the left, there’s what Packer calls “Just America” who largely grew up burdened by the dismal economic fallout from Clinton’s triangulation: drowning in unpayable student debt, overeducated and underemployed, unimpressed by the sight of people of color in high places—a generation that grew up suspicious of what other generations took for granted. “Just America” includes millennials, social justice warriors, the concept of identity politics, “wokeness,” and the pervading concern with how “a whole system of oppression can exist within a single word.” Plenty has been said about the excesses of tone policing and cancel culture, but it’s good to be reminded that college students complaining about “cultural appropriation” over the ingredients of a cafeteria sandwich is less significant than how “the $12-an-hour dining hall workers reacted with bemusement, or sullen rage.”

Packer offers three historical examples of Americans who, in their different ways, were able to break out of the usual ideological molds. Francis Perkins, the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet, turned her boots-on-the-ground activism and social work into official state policy for the New Deal. Horace Greeley tramped into New York City from rural New England to become an influential journalist whose anguished reckoning with the Civil War almost broke him. And special attention should be paid to Bayard Rustin, the brilliant mid-20th century Black civil rights organizer whose sexuality consistently victimized him both within and outside the movement. Each of these figures “show us ways of being American that we’ve forgotten—that can fortify and instruct us in our own crisis.”

And a crisis is indeed what it is. Even though Trump certainly brought it to a boil, the truth is that he’s a symptom of a much deeper malaise; Packer is right to say that “the question is not who Trump was, but who we are.” Therefore we must try to establish a common set of terms and references, assuming one still wants what some philosophers call “an ideal speech community” of shared communication. Last Best Hope attempts to point towards that direction. It’s the kind of book you can earnestly give your relatives for Christmas—whether or not they agree with Packer’s assessment, at least it will get them talking.

The Daily Beast contacted Packer via email about the motivation for Last Best Hope, why each of the four Americas is a dead end, the alliance between Free and Real America, the lack of one between Smart and Just America, what an American version of equality truly looks like, and what it means to listen to those you disagree with.

What made you want to write this book?

During the pandemic I was unable to travel and report—I was stuck with myself, my thoughts, my books. I decided to make a virtue of necessity and try to synthesize ideas I’ve been wrestling with over the past decade or so into a book-length essay or political pamphlet. And to do it in the middle of a crisis year so that I could try to push people’s thinking in a better direction.

I think the four Americas model is pretty accurate, but I’ve heard some criticism that it’s reductive. As you point out, American life is notoriously complex, dynamic, and multifaceted. What do you think about the difficulties in outlining the different narratives?

Any taxonomy of this kind is by definition reductive. I tried to show the influences, complexities, contradictions, and interrelationships of my four narratives in order to avoid slipping from the reductive into the simplistic. These narratives don’t attempt to be a complete portrait of American society—they are the four that have dominated my adult life. As such they leave a lot out.

You say that “I don’t particularly want to live in” any of the four Americas. Do you think one of them will become predominant in the next few years? Do you see any particular narrative especially gaining or losing national influence?

I don’t think any of them can prevail or even predominate. Each of them leads into a dead end. But at the moment Real America and Just America—the rebellious narratives that have risen from below in reaction to the failures of the other two, more elite narratives—have the energy and confidence and the political force of “negative partisanship,” as well as the generational advantage.

Sometimes it seems to me like the biggest political problem is how Free America and Real America managed to create a political allegiance even though their interests ultimately seem to run counter to one another. At times this seems impossible to overcome, especially on the local level. Why do you think these two narratives about America managed to join forces? How can that alliance be broken? Or is that impossible?

There’s been a political alliance between conservative elites and populists, mostly evangelical Christians, since the 1980s. The populism has taken over the culture and energy of the right, while the policies of the elites remain fixed and politically dominant. What they share is dislike, even hatred, of government, though for different reasons. So their unity is almost entirely negative, which is one reason why there’s almost no creative policy thinking in the Republican Party.

Breaking the alliance is extremely hard—at least, none of the efforts in the past few decades have been very successful, although for a short time Barack Obama appeared to have some success. I continue to think that the only possible way is to avoid hyperpoliticizing the culture wars, and instead focusing on policies and language that speak to the shared aspirations and desires for material improvement of the bottom 60 percent or so of Americans.

On the left side of the spectrum, it’s clearly not as easy for Smart America and Just America to align as it is for the right. Do you think the two sides can come together in some way? Or are their differences ultimately insurmountable?

This is mostly a generational conflict, and unusually bitter like many family arguments. In cultural institutions the older generation of Smart Americans have acquiesced to the demands of Just America. But in politics, those demands have often appeared self-defeating, and so that is where the battle is being fought. I fear that in the short term this battle is going to strengthen the alliance between Free and Real America.

Why did you choose Greeley, Perkins, and Rustin as your historical examples? What can they each tell us that we need to hear now?

I admire all three, for different reasons. Because they’re not the best-known Americans, I wanted to tell their stories. Also, they all show a way to be both progressive and patriotic. They all pushed very hard for fundamental change toward greater equality, and yet they did so by speaking to a shared American identity that includes far more people than it excludes. They show how constricting and self-destructive our four narratives have become. There are other ways to be American than the ones we know.

As an alternative to the four narratives about America, you propose “Equal” America. Say more about what you mean by that and what it looks like politically.

In American history, equality—even more than freedom—is the dominant theme. It’s the first idea in the Declaration; the key word for Greeley, Perkins, and Rustin; the “passion” that Tocqueville wrote was the most distinctive feature of our democracy. In none of these contexts does it mean something like equality of outcomes. It means—at least, I interpret and want it to mean—a democratic equality, in which everyone can look everyone else in the eye as a fellow human being and citizen. It’s a matter of dignity and respect.

For Whitman it’s almost a spiritual state. It tolerates no permanent hierarchy of groups, no subordination or exclusion or privilege by birth, no disparity in power that allows some people to oppress others. Of course this equality requires certain social and economic arrangements—we’re not just talking about equality under the law. For Frances Perkins, it required the pillars of the New Deal; for Bayard Rustin, the end of American apartheid and equal access to education, health, employment. So, in politics, it looks at people as individuals equally deserving of these benefits of citizenship, and at government as their guarantor.

I think one problem that isn’t as widely discussed as it should be is that people of all stripes tend to think that we need to “listen” to each other more. Of course, listening is a good thing to do, in principle, but I worry that most of the time people tend to confuse “listen” with “agree” or “validate.” I can’t tell you how many times people I know (on either side of the fence) insist that they’re not being “listened to” when they’re being criticized or challenged, even if it’s being done in good faith.

I think we don’t know how to listen, because all of the incentives in technology and culture and politics go against listening. But by listening I don’t mean agreeing, which is impossible. I mean making the imaginative effort to understand another’s experience and outlook. Even if it’s radically different from yours. Even if it upsets you. This is what journalists are supposed to do. We don’t do it in order to arrive at some facile agreement or compromise. We do it in order to be able to go on living together in a democracy without tearing ourselves apart.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.