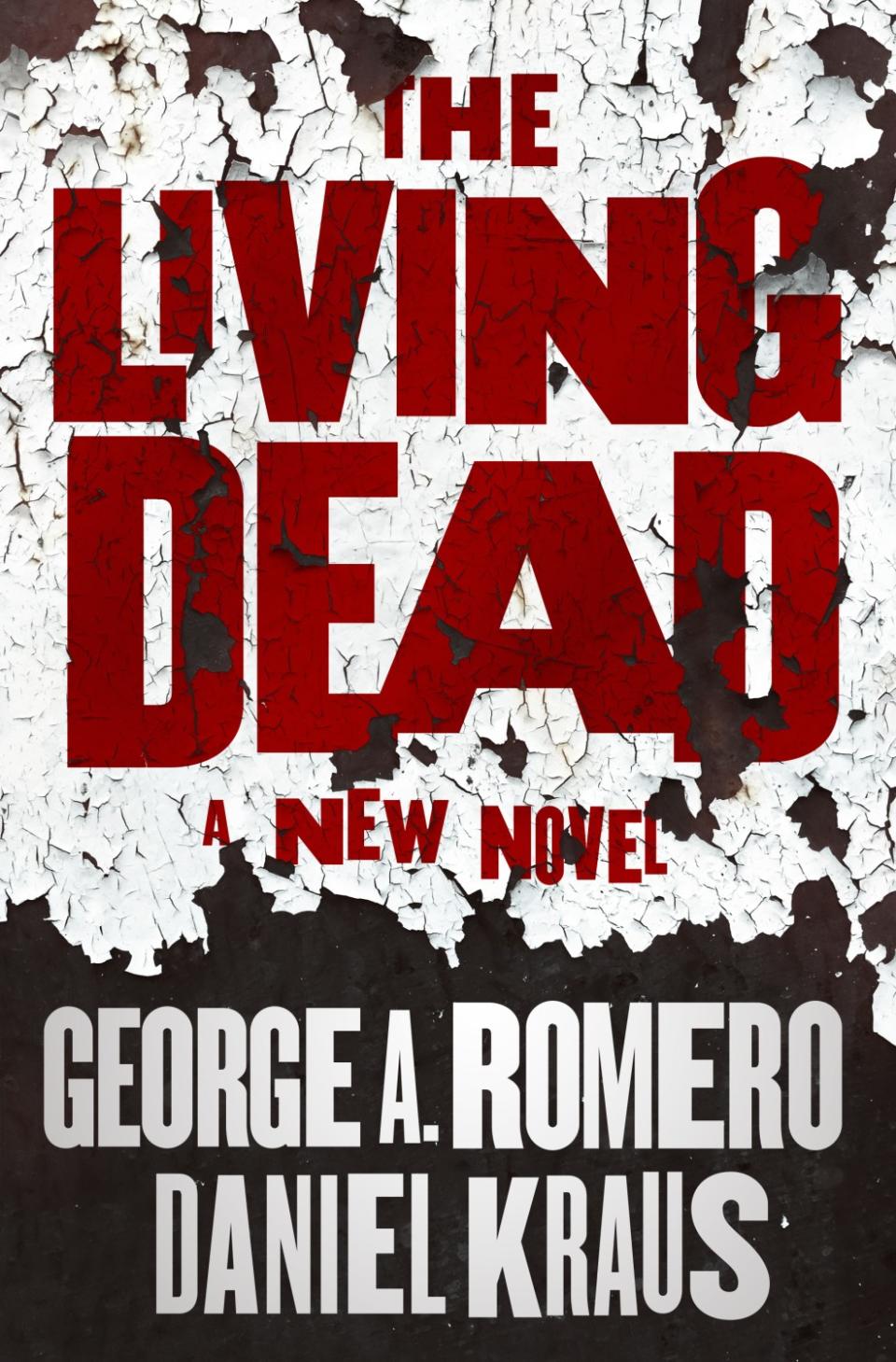

George Romero is alive! With a posthumous zombie novel as urgent as his '60s classics

After George A. Romero died in 2017, his wife, Suzanne Desrocher, began the process of bringing the legendary zombie film director back from the beyond. Well, OK, it wasn’t Romero himself she hoped to reanimate, but his final project: an epic zombie novel called “The Living Dead.”

Out this week, it’s a brisk 656 pages, filled with the gore, the tension and the social commentary of Romero classics like “Night of the Living Dead.” It’s also, accidentally, a timely saga about a mismanaged pandemic and the societal collapse that follows. And while Romero’s movies tended to keep a tight focus, this story — freed from Hollywood’s meddling and budgetary constraints — sprawls across the nation. There are so many sympathetic protagonists that it’s impossible to predict who will survive and who will be eaten. (Spoiler: Many of your favorite characters will not make it to the end, at least not as humans.)

The finished book isn’t Romero’s alone; it came to life only with the help of Daniel Kraus, the best-selling writer of a slew of horror and fantasy novels as well as, with Guillermo Del Toro, the concepts and novels behind “Trollhunters” and “The Shape of Water.”

Romero had worked on this book on and off for years, and while he’d written hundreds of pages, many were still in first-draft shape, the story nowhere near finished. He and Desrocher never spoke about someone else finishing his labor of love. “After his [lung cancer] diagnosis, he didn’t want to discuss business,” Desrocher says. “But after he died, I felt this was an artist with a huge amount of work left to share.”

She conferred with manager Chris Roe about how the book might be finished. Roe happened to be from the same Iowa hometown as Kraus, who he knew revered Romero; in 2006 Roe had even introduced the two creators.

“I really take Romero seriously,” says Kraus, whose passion extends beyond the zombie films to works like “The Crazies” and “Martin.” “The stuff he talked about is imprinted in my DNA; it’s almost gospel. I modeled my career after the kind of stories he told and the warnings he gave.”

After one meeting, Desrocher knew she’d found the writer to finish “The Living Dead.” “He was totally the right guy,” she says. “You could feel his passion.”

For Kraus, the project was irresistible, and not just because he idolized Romero. “I’m really into challenging myself and throwing up obstacles,” he says — from the experimental slang in his last novel, “Blood Sugar,” to his collaborations with Del Toro. “It’s about forcing myself to work in different ways. Sometimes that produces the best stuff.”

On “The Living Dead,” the challenge was honoring Romero’s existing writing and his patchy plans. Kraus says the finished novel is about half Romero, half Kraus.

“Sometimes there was a snippet he wrote and it no longer worked where he had it, but I’d say, ‘Maybe I can get the spirit of that in somewhere else’ or ‘Maybe this character can be combined with that one,’” he says. There were large gaps in the middle and the end. “I had to get from A to Z but fill in B and D and H and so on. It was a fascinating and unique puzzle. I spent a lot more time thinking and planning than I normally do.”

Kraus read interviews and scholarly analyses, talked to Desrocher and others close to Romero, consumed the filmmaker’s favorite movies and music, and studied all the films — including a long-lost Romero, “Amusement Park.” (Desrocher is now seeking its release; as for screen rights to “Living Dead,” she plans to be cautious: “I’m not prepared to sell my soul and George’s.”)

Most useful to Kraus, of course, were Romero’s six zombie films, starting with the 1968 classic “Night of the Living Dead.” “They were hugely helpful, especially once I put them in the chronological order of the zombie epidemic, which showed how he thought the first five years of that played out,” Kraus says. “Having all that data [helped me] intuit what year nine or 10 might be.”

It felt important to honor Romero’s firm parameters for zombie behavior. “There have been endless variations on zombies, but he largely wasn’t interested in them,” Kraus says, adding that Romero disdained fast-moving or brain-eating ghouls. “He wanted biologically logical creatures. How can legs that are rotting run? Why bother with the hard skull when you have an entire soft body.”

This explains why the novel’s characters don’t immediately recognize the zombies for what they are. It’s always a meta-question hanging over genre movies: Haven’t these people seen any movies? Shouldn’t everyone know the best practices for killing vampires, werewolves and zombies?

“It’s a paradox, but when dealing with a George Romero project you have to presume George Romero didn’t exist and that zombies didn’t become these pop culture figures,” Kraus says. “That would have been too meta, and George would not have been interested in it at all.”

Kraus’ research and kinship with Romero freed him to take creative risks. He knew to avoid “bells and whistles” and stay tight on “the disintegration of the people around the zombies.” But he wanted to make the most of what a novel could do that a movie couldn’t. Romero had the idea of writing sections from the zombies’ points of view; Kraus ran (or staggered slowly) with the concept. This twist creates a weird empathy for the creatures. Readers may see the book as dealing with a zombie plague, “but it seemed clear to me that there was a human plague, and the zombies are the planet’s way to flush out the toxins.”

Romero was a surprisingly tricky collaborator, considering his condition. He kept coming “back from the dead,” Kraus says; while he was writing, another hundred pages were discovered, then a nine-page letter in which Romero sketched out characters and plot threads — some of which Kraus had already moved beyond. He strove to honor his late partner’s wishes whenever he could. “It was amazing how much it felt like a standard collaboration,” he says.

Then there were unpredictable events on a more global scale. Romero started toying with the idea of “The Living Dead” decades ago. But a pandemic that causes panicking people to lock themselves away while simmering racial divisions and violence fuel further death and destruction sounds, well, a tiny bit relevant.

“I think it’ll cut a little more sharply now,” Kraus says. “Romero was very pessimistic; he felt in a crisis we would fail to come together.” And he was right. “Now we can’t even come together to put a slip of cloth over our faces. So to think we would be able to work together to stop a zombie epidemic is hard to swallow. It’s playing out in front of us.”

While racism, xenophobia and greed are universal traits, the toxic stew of violence, mistrust and sanctimonious individualism feels uniquely American. The novel hints at how the zombie pandemic plays out elsewhere in the world. Kraus believes some other countries would handle it better, but there are no guarantees: “You can have a community that is really quite strong, but one wrong guy who speaks just loudly enough can really ruin things.”

In “The Living Dead,” one such person calls the outsiders thugs and rants about building walls. And yet his ideas aren’t totally wrong. “Terrible people sometimes do the right thing, and good people sometimes do the wrong thing,” Kraus says. “We were not thinking that any one of us is going to be able to act entirely honorably when [it all] goes down.”

Kraus never considered softening the novel for an audience scarred by recent events. That would dishonor his zombie collaborator. “George always intended this to be a dark book,” Kraus says. “People just do not learn.”