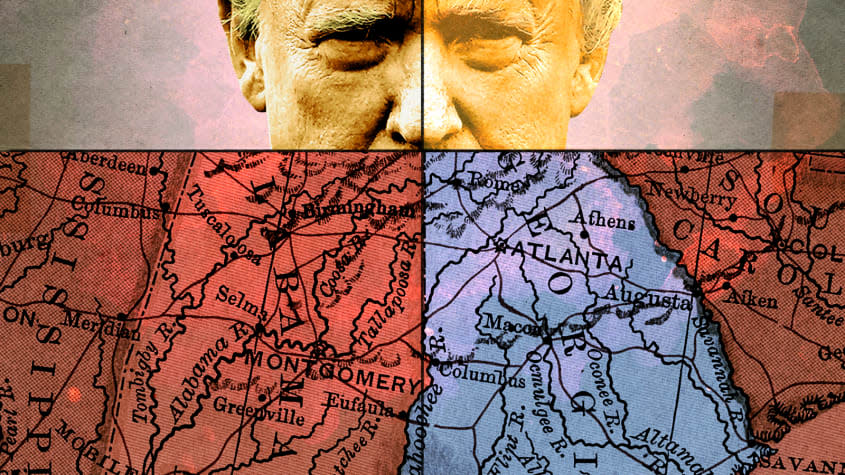

How a Georgia D.A. aims to get to the bottom of the Trump election interference scandal

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In February 2021, Fani Willis, the district attorney of Georgia's Fulton County, announced her office was launching an investigation into alleged attempts by former President Donald Trump and his allies to overturn the 2020 election results in Georgia. Since then, a special grand jury has been seated and several high-profile names have been called to testify, including Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.). Here's everything you need to know:

What prompted the investigation into election interference in Georgia?

Following President Biden's victory, Trump and his allies began focusing on ways to challenge the results in states narrowly won by Biden. On Jan. 2, 2021, Trump called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) and asked him to "find 11,780 votes" to overturn Biden's win. The Washington Post reported on the hour-long call, and also revealed that Raffensperger's deputy said Trump tried to reach the secretary of state 18 times before he got through to him; his calls had been sent to interns because the office thought it was being pranked.

On Feb. 10, 2021, Willis announced her office was launching a criminal investigation into the efforts to overturn the election loss, with the probe including but not limited to "potential violations of Georgia law prohibiting the solicitation of election fraud, the making of false statements to state and local government bodies, conspiracy, racketeering, violation of oath of office, and any involvement in violence or threats related to the election's administration."

What has happened since then?

During an interview with The Associated Press in January, Willis confirmed that the investigation's scope includes the Jan. 2, 2021, phone call between Trump and Raffensperger; a November 2020 call between Graham and Raffensperger; Rudy Giuliani's three appearances before Georgia state legislative panels in December 2020, during which he made false claims about the election and voting machines; and the Jan. 4, 2021, resignation of the U.S. attorney in Atlanta. The investigation is also focused on a slate of fake Republican electors who signed a certificate falsely stating that Trump won the election.

In late January, Willis asked for a special grand jury in the investigation, writing in a letter to Fulton County Superior Court Chief Judge Christopher Brasher that her office has "received information indicating a reasonable probability that the state of Georgia's administration of elections in 2020, including the state's election of the president of the United States, was subject to possible criminal disruptions." Her request was granted, and the special grand jury was impaneled in May.

What is the job of the special grand jury?

This special grand jury is focused solely on the investigation into Trump and his allies and can meet for up to a year. It does not have the power to indict, but "what it can do is issue a final report that would effectively be a roadmap as to all of the evidence it reviewed and make recommendations as to which charges, if any, would be appropriate based on that evidence," Gwen Fleming, a former district attorney in Georgia, told WABE. It will then be up to Willis to decide which individuals, if any, to charge. There are 23 Fulton County residents on the special grand jury, plus three alternates.

What specific crimes might the special grand jury be looking at?

In Georgia, there are several state laws against interfering in the voting process and elections, and WABE legal analyst Page Pate said "there's a good argument that Trump's phone calls to Raffensperger could qualify as solicitation to interfere in the election and the phone call itself could be a crime."

Under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, it is illegal to make false statements, and Page said in Giuliani's case, making two or more false claims in front of Georgia state legislative panels could show enough of a pattern to lead to a racketeering charge. "And then you have to have this group, an enterprise they call it under RICO, which would be the Trump campaign," Page continued. "RICO violations carry a mandatory minimum of five years in prison. So it's a serious crime."

Who has been called to testify before the special grand jury so far?

The first two witnesses to testify before the special grand jury were Raffensperger and his wife, Tricia. Several people close to Trump have been subpoenaed, including Graham, Giuliani, former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, and lawyers L. Lin Wood and John Eastman, who pushed a last-ditch effort to overturn the election, putting forward the theory that former Vice President Mike Pence could reject the electors on Jan. 6 and declare Trump president. Giuliani and Eastman both testified before the special grand jury in August, with Eastman citing attorney-client privilege and invoking his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Have all the witnesses cooperated?

No. Meadows, who was on Trump's call to Raffensperger and made an unannounced visit to Cobb County in December 2020 to try to watch the audit of absentee ballots, fought against having to testify. His attorney argued before a South Carolina court that the special grand jury is not criminal in nature, so lacked the standing to compel Meadows' appearance, but Circuit Court Judge Edward W. Miller noted that the Fulton County judge overseeing the special grand jury ruled that it was criminal in nature, and ordered Meadows to testify.

As for Graham, Willis wants to question him on why he called Raffensperger to ask about Georgia's procedures for handling and discarding absentee ballots. Graham argued that his role in Congress protects him from having to testify before the special grand jury. Two federal courts ruled that under the speech or debate clause of the Constitution, Graham is only shielded from having to answer certain types of questions that have to do with his duties as a federal lawmaker. Graham brought his battle to the Supreme Court, and on Tuesday, the justices rejected his request to block the subpoena. His testimony could happen as soon as Nov. 17.

You may also like

Russia's 'catastrophic' missing men problem

7 scathing cartoons about Elon Musk's Twitter takeover

How the Justice Department might respond to a Trump 2024 bid