Georgia olives? New USDA temperature map suggests peaches might be a thing of the past

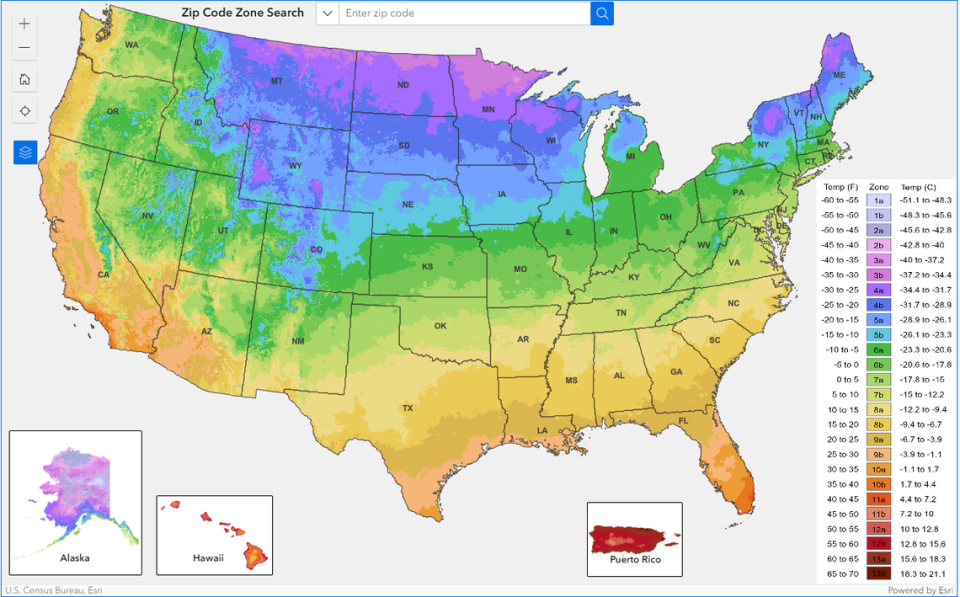

Climate change is showing its colors on a new map that reveals the coldest temperatures at which crops can survive – known as a “plant hardiness zone”.

The map, created by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), takes a 30-year average of the extreme minimum temperature for each year and then designates an area a certain zone within that temperature range so growers and farmers can know what will likely not survive.

“It’s something you should take a look at if you are interested in putting plants into the soil,” Pam Knox, an agricultural climatologist at UGA said. “More than half of the Southeast has jumped up half a zone.” Adding, “[Farmers] can grow warmer crops that are suited to warmer conditions. A lot of it has to do with rising temperatures from climate change.”

The last time the USDA released its plant hardiness map was in 2012. The temperature averages the USDA examined were between 1982-2012 versus the new map which averaged 1991-2020.

“The state of Georgia saw significant shifts,” Stephen Jessup, assistant professor of meteorology at Columbus State University said. “It’s a big shift for the whole country.”

The map also has a much more detailed resolution than the 2012 version.

“It’s like getting a new prescription for your glasses, you can see in finer detail. It brought out the contrast in North Georgia which has a lot of mountains,” Jessup said.

Peaches keep moving further north

In Georgia, more than half the state is now in zones 8a and 8b, meaning the coldest it may get in these zones is between 10-20 degrees Fahrenheit. The last map had temperature hardiness as low as 0 degrees in North Georgia and just a sliver of the state at 20 degrees near Brunswick.

“Right now apples only grow in the northeastern part of the state,” Knox said. “There may be a time in the future when apples aren’t grown commercially in Georgia.”

Apples typically thrive in zones 4-7, that is cold maximums at -30 to 5 degrees.

The Macon Telegraph reported on the issue with peaches earlier this year. Peaches (and nectarine) exports from the state of Georgia have decreased in the last two years.

Total fresh fruit exports in 2021 were $29.1 million and in 2022 it dropped to $23.5 million. Peaches (and nectarines) made up 11% of the valued exports in 2021, and just 7% in 2022, according to figures from the USDA Economic Research Service.

Columbus is one of the few places that stayed in the same zone as the 2012 update. However, the surrounding Harris and Chattahoochee counties jumped up 5-10 degrees F in hardiness.

Colder temperatures are better for fruit trees that require frost temperatures in the winter.

“The bad news is there are plants that need cold weather like peaches and blueberries,” Knox said.

There will be less success for peaches, pears, apples, and cherries. All perennial fruit trees need to freeze to create buds that are viable for pollination to produce fruit.

“Farmers are going to have to adjust,” Knox said.

Farmers will either have to change crops, change varieties, plant earlier in the year, or move further north to keep the same crop.

“Some [farmers] are experimenting with satsuma and tangerine, pomegranates, and olives,” Knox told the L-E.

The Olive Oil State

In 2011, 6th-generation farmer Easton Kinnebrew planted 10 acres of olive trees on his land in Americus, Georgia after he was unsuccessful with blueberries. Then, it was rare to find an olive farm in Georgia.

At 65 miles Southeast of Columbus, The New Era Farm is about as far north as you can get to successfully farm olives in Georgia.

“Easton planted olive trees where his great-grandfather grew peaches,” Jennifer Kinnebrew, New Era Farms head of sales and marketing said. “He started with blueberries but always wanted to do olives, or something different. He took notes from farmers at an olive farm in Lakeland, Georgia” (near the Florida border).

Kinnebrew’s 20-acre farm was experimental in early 2011. Five years later New Era Farms had its first harvest of Arbequina olives

“It typically takes anywhere from three to five years for the first harvest,” Kinnebrew said. “The first harvest took five years because we had a few frost days.”

The New Era Farm planted the other 10 acres in 2013, and again it took about five years for the first harvest.

Frost days are less and less likely for this part of Georgia, according to the new USDA map. The New Era Farm is located in zone 8b, according to the new map, meaning its frost threshold is anywhere from 10-20 degrees. 10 years ago, it was lower, in 8a at 5-10 degrees.

“When it gets to about 15 degrees and below, that’s when the olive trees struggle,” Kinnebrew told the L-E.

The USDA suggests that they will continue to release this map every decade.

“Plant hardiness zones are going to continue migrating to the north as warming continues,” Knox said.