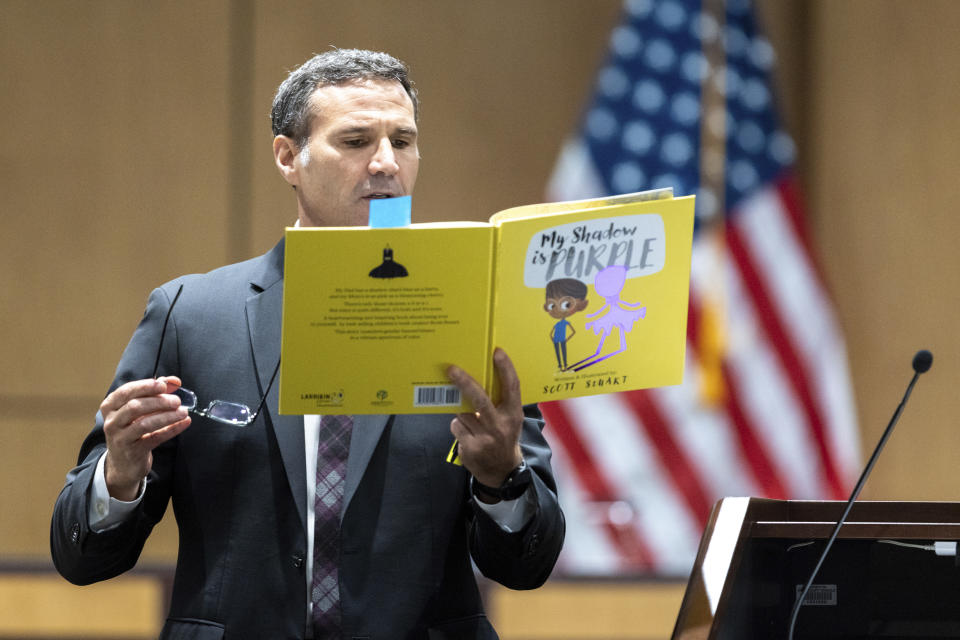

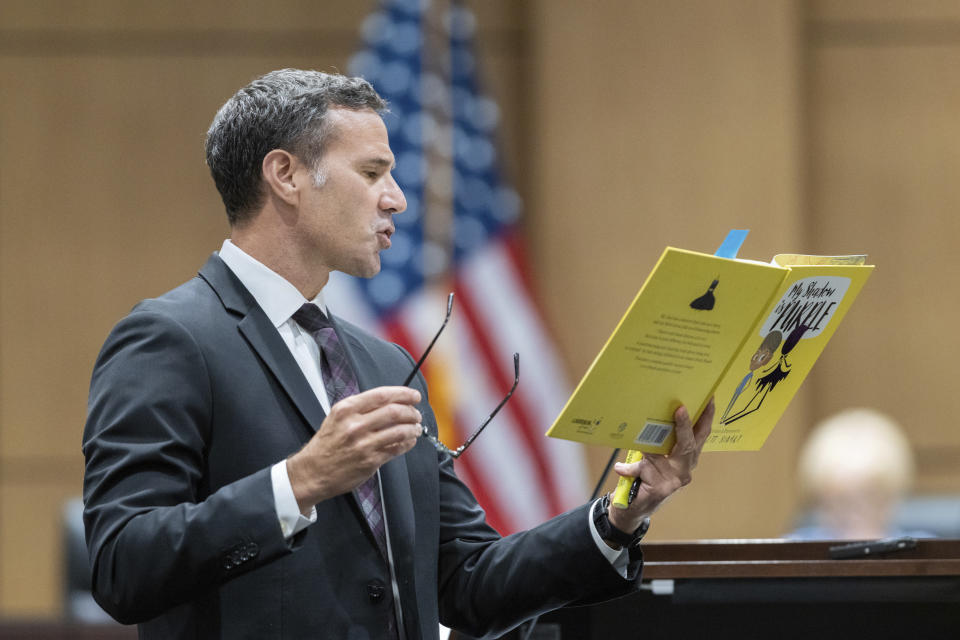

A Georgia teacher wants to overturn her firing for reading a book to students about gender identity

MARIETTA, Ga. (AP) — A Georgia public school teacher took the stand Thursday trying to reverse her firing after officials said she improperly read a book on gender fluidity to her fifth grade class.

Katie Rinderle had been a teacher for 10 years when she got into trouble in March for reading the picture book “My Shadow Is Purple" at Due West Elementary School in suburban Atlanta’s Cobb County.

The case has drawn wide attention as a test of what public school teachers can teach in class, how much a school system can control teachers and whether parents can veto instruction they dislike. It comes amid a nationwide conservative backlash to books and teaching about LGBTQ+ subjects in school.

“This termination is unrelated to education," Craig Goodmark, the lawyer defending Rinderle, argued Thursday. "It exists to create political scapegoats for the elected leadership of this district. Reading a children’s book to children is not against the law.”

Officials in Cobb County, Georgia's second-largest school district, argue Rinderle broke the school district's rules against teaching on controversial subjects and fired her after parents complained.

“Introducing the topic of gender identity and gender fluidity into a class of elementary grade students was inappropriate and violated the school district policies,” Sherry Culves, a lawyer for the school district argued Thursday.

Rinderle countered that reading the book wasn't wrong, testifying that she believed it “to be appropriate” and not a “sensitive topic.” She argued Thursday that the book carries a broader message for gifted students, talking “about their many interests and feeling that they should be able to choose any of their interests and explore all of their interests.”

Cobb County adopted a rule barring teaching on controversial issues in 2022, after Georgia lawmakers earlier that year enacted laws barring the teaching of “divisive concepts” and creating a parents' bill of rights. The divisive concepts law, although it addresses teaching on race, bars teachers from “espousing personal political beliefs.” The bill of rights guarantees that parents have “the right to direct the upbringing and the moral or religious training of his or her minor child.”

“The Cobb County School District is very serious about the classroom being a neutral place for students to learn," Culves said. "One-sided instruction on political, religious or social beliefs does not belong in our classrooms.”

Goodmark argued that a prohibition of “controversial issues” is so vague that teachers can never be sure what's banned, saying the case should be dismissed.

The hearing took place under a Georgia law that protects teachers from unjustified firing. A panel of three retired school principals will make a recommendation on whether to fire or retain Rinderle, but the school board in the 106,000-student district will make the final decision. Rinderle could appeal any firing to the state Board of Education and ultimately into court.

Culves called Rinderle as the district’s first witness, trying to establish that Rinderle was evasive and uncooperative. Cobb County says it wants to fire Rinderle in part because administrators find her “uncoachable.”

“The school district has lost confidence in her, and part of that is her refusal to understand and acknowledge what she’s done,” Culves said. She cited Rinderle’s failure to take responsibility for her actions and to apologize to parents and the school principal as further reasons why the district has lost confidence.

Under questioning from Culves, Rinderle repeatedly said she didn’t know what parents believed or what topics might be considered offensive.

“Can you understand why a family might want the chance to discuss the topic of gender identity, gender fluidity or gender beyond binary with their children at home first, before it is introduced by a public school teacher?” Culves asked at one point.

Culves argued that district policies meant Rinderle should have gotten her principal to approve the book in advance and should have given parents a chance to opt their children out. Rinderle said students voted for her to read the book, which she bought at the school's book fair, and that it wasn't common practice to get picture books approved.

District officials argued that Rinderle should have known that books were a sensitive area after parents had earlier complained when she read “Stacey's Extraordinary Words,” a picture book about a spelling bee by Stacey Abrams, who was then running for Georgia governor as a Democrat. But Rinderle said her principal read the book, told her there was “nothing wrong with it,” and said she would handle complaints.