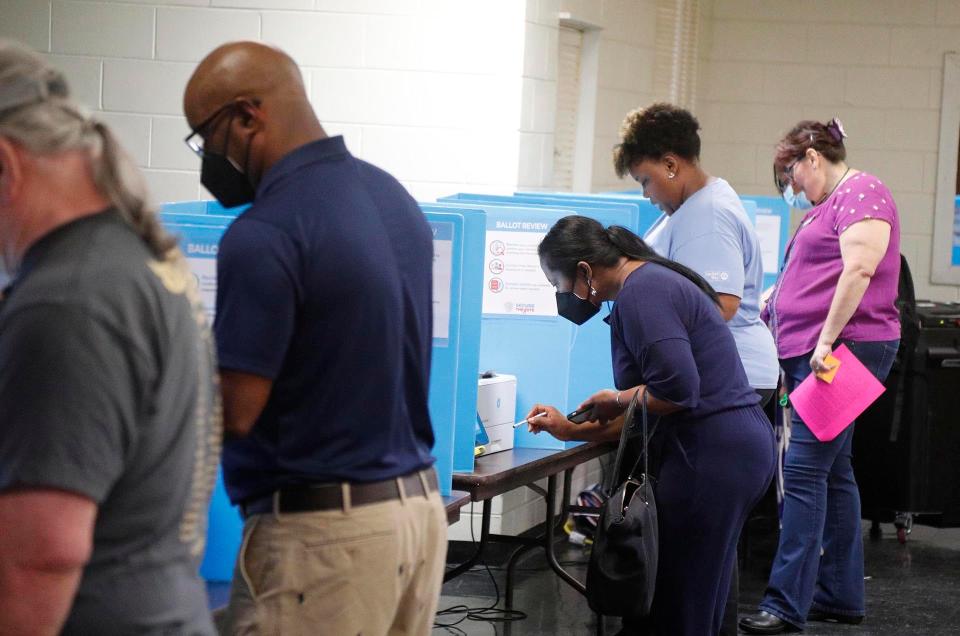

Will Georgia's 'election integrity' law hurt midterm turnout? Data from primary offer clues.

Despite widespread concerns that a controversial new law would deter many Georgia residents from casting ballots, voter turnout in the May primary rose across every category of race, gender and geography, an analysis by the USA TODAY Network found.

Experts in Georgia politics said the increase largely reflected an enormous outpouring of voter interest since the 2020 presidential election and subsequent national news events that have electrified the electorate.

The turnout growth, measured since the last midterm primary in 2018, was not uniform. It was stronger among white voters than Black, and participation rose more in the Republican primary than in Democratic contests. Black turnout dropped in some pockets of the state.

But political analysts said those disparities probably don’t tell us much about what will happen in November, with marquee races for governor and U.S. Senate on the ballot.

On Friday, the Georgia Secretary of State’s office said that in the first four days of early voting for the November election, Georgians exceeded early voting turnout for the equivalent period in 2018 and came within “striking distance” of turnout at the start of the 2020 presidential election.

In the end, voting rights advocates say participation by voters of color rose during the primary thanks, in part, to a concerted effort in May to overcome obstacles created by Georgia’s Senate Bill 202.

The 2021 legislation:

Limited the number of polling places.

Required a photo ID for people to get absentee ballots.

Made it harder to vote in a precinct other than where the voter lives.

“We provided more rides to the polls than we ever had before,” said Helen Butler, executive director for The People's Agenda, an organization focused on turnout among communities of color in Georgia.

Georgia voting law explained: Here's what to know about the state's new election rules

Democratic U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock, who is in a closely watched race with Republican Herschel Walker, said at an Oct. 14 debate that the new voting rules are a problem regardless of what’s happened to turnout.

“There is no question that SB 202 makes voting harder, and that is the intent,” Warnock said. “And the fact that many voters are overcoming this hardship doesn’t undermine that reality.”

Supporters of the law say that the high turnout in May showed it’s possible to tighten voting requirements without infringing on voting rights.

“We have struck the balance, we think, between election security and voter convenience,” Mike Hassinger, public information coordinator on voting and elections for the secretary of state, told the USA TODAY Network’s Georgia GO Team in September. “We want to make it as easy as possible for registered, eligible voters to vote.”

Turnout up

The USA TODAY Network set out to identify trends by combining a list of Georgia voters registered in 2018 with one from 2022 – more than 8.5 million people – and then analyzing their voting histories. The result was a highly detailed demographic view of how voting changed after the new election law took effect.

Hispanic voters had the smallest increase of any racial or ethnic group, about 1 percentage point statewide. Native Americans and Asian Americans had larger increases in turnout but remained, with Hispanics, near the bottom for participation rates among all racial and ethnic groups.

White women, meanwhile, had some of the biggest increases. The rates for white women in suburban and rural areas rose by 12 and 13 percentage points, respectively.

Turnout rates for Black men and women in all types of geography also rose, but to smaller degrees. Black voter turnout actually fell by a percentage point or more in 22 of Georgia’s 159 counties, many of them small in population and almost all rural. In one, rural Clinch County with under 5,000 voters, Black turnout fell by 22 percentage points.

White voter turnout fell in only two counties, Augusta’s Richmond County and Taliaferro County, between Augusta and Athens.

Georgia voting laws: For nearly 60 years, Georgia's voting rights laws have shifted with the political winds

The net result of all these shifts?

Although participation grew across the board, the gap between white and Black voting rates widened in 2022, and consequently, white voters comprised a slightly bigger share of all Georgians casting a vote in May than they did four years earlier.

The Georgia GO Team found that Black voter turnout rates ranged from 16% among men in Georgia’s one urban county, Fulton, to 25% among Black women in suburban counties. White turnout ranged from 28% among urban white men to 35% among rural white men.

Going back further in time, the Brennan Center for Justice found that the disparity between overall white and Black voter turnout in May was greater than in any year since 2014.

But race was not the only factor behind these numbers.

Black voters lean Democratic, white voters lean Republican. And the competitiveness of the two-party primaries was “uneven,” said Andra Gillespie, a political scientist at Emory University who researches political participation and African American politics.

Republican incumbents Gov. Brian Kemp and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger drew high-profile challengers backed by former President Donald Trump, while Warnock and Stacey Abrams faced little to no opposition.

There were lopsided levels of excitement in the two parties’ primaries. Georgia voters cast more than three times as many Republican ballots as Democratic ballots, a surge that may have helped to boost turnout more among white voters than Black voters.

And there’s further evidence that interest in each party’s primary may have helped shape the demographics of those who voted.

Older voters, who skew more Republican, also had the highest increase in turnout. Voters ages 68 to 87 posted the highest turnout rates of any age group and had the most significant increases in turnout this spring.

White men in that age range had a nearly 60% turnout rate in the 2022 primary. Voters 18-37 had turnout rates of under 10%.

Gillespie said one simple takeaway is that youth turnout rates “are abysmal.”

Advocates worry voting is still hard

While Georgia’s SB 202 law gained national attention mainly for restricting aspects of voting in the name of preventing fraud, it also contained provisions that might ease voting.

On one hand, the law limited ballot drop boxes to one location per county or one per 100,000 active voters, whichever number is larger. It also compressed the timeframe in which voters may request an absentee ballot, from a window that spanned 180 days to 4 days before election day to a period of between 78 and 11 days before the election.

On the other hand, the law also formally made the drop boxes, which were created as a temporary measure in the 2020 pandemic year, a permanent part of state election law. SB 202 also mandated each county include at least one Saturday to the period in which people may cast early votes.

Georgia voter rights guide: What you need to know before you cast a ballot

Hassinger, the secretary of state’s spokesman, pointed to another element of the law he said may have improved the process for voters who prefer absentee ballots.

Third-party groups used to mail multiple voters applications for absentee ballots even after the person had actually voted, Hassinger said. The new law requires that any group sending out a blank absentee ballot application must first verify that the recipient hasn’t already voted. Hassinger said that has reduced confusion.

Hassinger said May’s big turnout proved critics were wrong when they said the law was aimed at selectively taking away people’s voting rights.

“We've broken records in all categories,” Hassinger said. “That's the worst case of voter suppression ever. It’s actually having the opposite effect.”

But opponents of the law say rising turnout doesn’t mean a voting system is fair to everyone.

"It's important to really think about what a free and fair election process looks like from the standpoint of a voter," said Esosa Osa, deputy executive director for Fair Fight Action.

Osa said three questions especially matter: "Are you able to register to vote and stay on the rolls, are you able to cast your ballot without undue burden, and are you able to have that ballot counted fairly?"

What to know to vote: Early voting is underway in the 2022 Georgia midterm election

Multiple voting rights groups – The People's Agenda, All Voting is Local, and the Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials, along with Fair Fight Action, an organization founded by gubernatorial candidate Abrams – told the USA TODAY Network they are concerned specifically about the changes to the new absentee ballot system. Several said they felt it was targeted at a system that underrepresented voters in particular had used heavily in 2020.

Although rejection rates for absentee ballots cast went down, the advocates noted that applications for absentee ballots were increasingly rejected. According to an analysis by The Washington Post shortly after the election, the number of applications rejected went from 1.4% to 2.3%, often for missing the new, shortened deadline to apply.

Several organizations are encouraging people to vote early and in person, to avoid issues with absentee ballots.

The new restriction on the number of ballot boxes is also a concern. Kristin Nabers, the Georgia State Director for All Voting is Local, said that in metro Atlanta, more than half of voters used drop boxes to vote in 2020.

“We know now that the drop box rollbacks are affecting cities and suburbs the most, and of course, that is where the majority of our voters of color live,” Nabers said.

Osa said the fact voters have been able to clear hurdles in the new law does not mean that the law itself is without impact.

“You put in all of these hurdles for voters, but they still managed to jump over each and every one,” Osa said. “That doesn't mean that that is a fair system.”

To look at voter turnout, the USA TODAY Network compared files provided by the Georgia Secretary of State office indicating who voted, in what county, for what election, and using which party ballot, from after the primary in 2018 and 2022. These also include a voter ID number, which was matched with voter rolls from 2018 and 2022. Voter rolls include information including the county of residence, race, gender, registration, year of birth and more. Because voter data does not include the exact date of birth, ages are estimated by subtracting the year of birth from the year of the election.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Will new Georgia voting law affect voter turnout in November election?