Gerald Wiener, Kindertransport refugee who became an eminent animal geneticist – obituary

Gerald Wiener, who has died aged 97, arrived in Britain as a penniless 12-year-old refugee from Nazi Germany on a Kindertransport and went on to become a distinguished scientist working on the genetics of farm animals at what would later be merged into the Roslin Institute, where he assembled a team that included many of the scientists who would go on to clone Dolly the Sheep.

Wiener’s key contributions to animal genetics include mapping out how genes flowed from a relatively small subset of influential herds or flocks to the wider population, and how this “pyramid” of genetic inheritance could be used for improving breed quality – an idea fundamental to modern livestock breeding.

Subsequently, during research into the causes of variation in productivity of cattle and sheep, he discovered that deaths from swayback, a non-treatable condition in young lambs caused by copper deficiency, was heavily influenced by breed. This led him to conclude that the absorption of dietary copper from the gut was strongly influenced by genetics, and that an understanding of metabolic “pathways” – the chemical reactions in living cells essential to maintain bodily functions – often offer better predictions of animal health and productivity than such indicators as body weight or volume of milk.

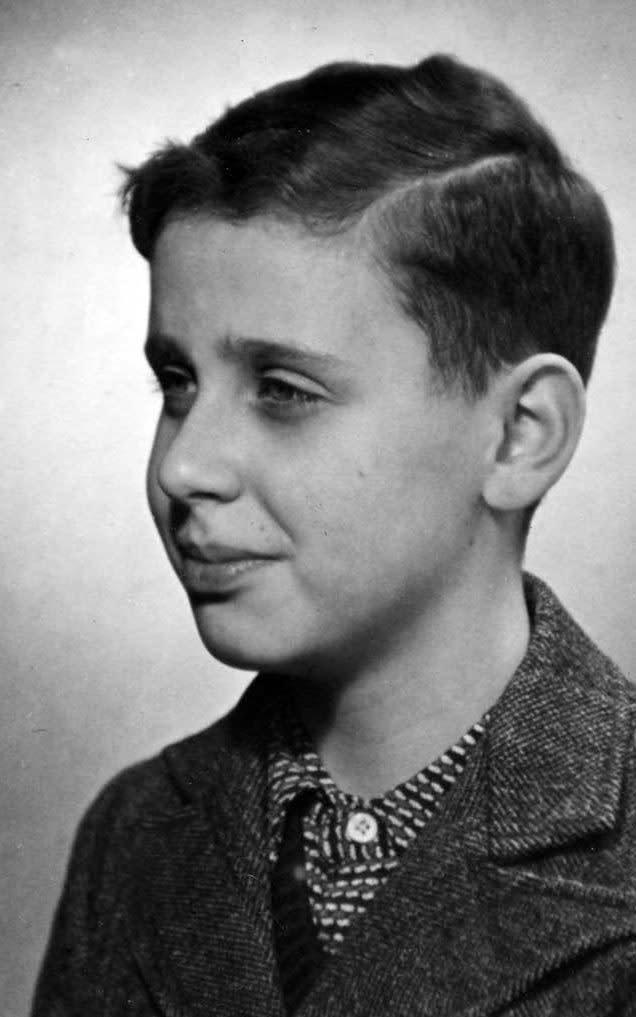

An only child, he was born Horst Wiener in Küstrin, Germany (now Kostrzyn, Poland) on April 25 1926 to secular Jewish parents, Paul and Luise Wiener. His parents divorced when he was two and he was brought up by his mother in Berlin.

As the Nazis consolidated their hold on Germany, young Horst was forced to leave school and after Kristallnacht, when Nazis looted and vandalised Jewish-owned businesses, his mother sought ways for her son to escape. “At school I had a really close friend, Hardy Seidel, who came to Britain first,” he recalled. “My mother wrote to them and they brought me to the attention of Save the Children and that’s how I came over on the Kindertransport in March 1939.”

While many children were terrified of leaving their homes and parents, young Horst recalled the journey as an adventure: “There were over 100 of us on the train, At Hamburg docks we were met by an enormous ship, SS Manhattan. It was so exciting. The crew gave us balloons and cakes. Of course, I was seasick.”

Fortunately his mother was able to join him a couple of months later, having obtained permission to train as a midwife, and they settled in Oxford, where Horst changed his name to Gerald and became friendly with Rosemary and Ruth Spooner, Christian Socialists and relations of the Rev Spooner who gave his name to “spoonerisms”.

The Spooners had a great influence on the young boy: “None of my family had ever been to university, they were shopkeepers, but the Spooners thought ‘this boy’s too bright to be a farm labourer or something like that’ and set me on the road to university.”

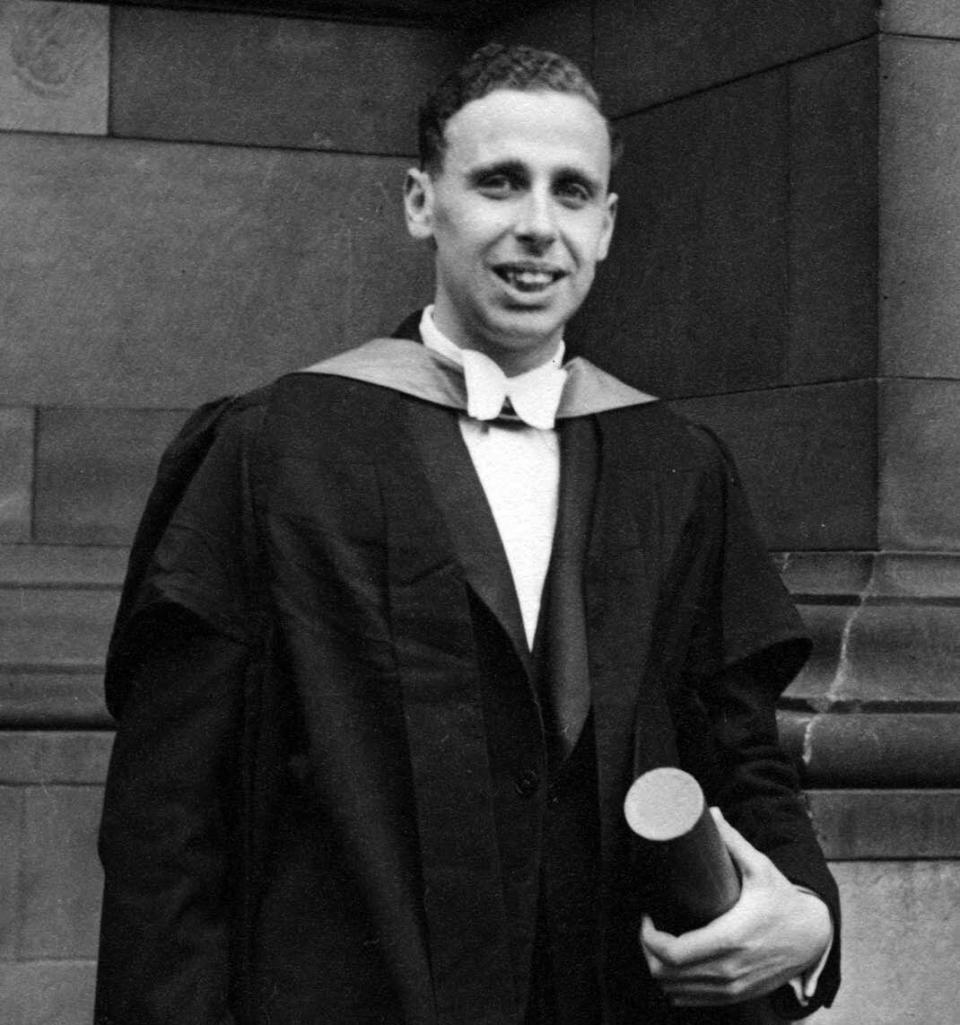

Under their influence he also converted to Christianity, eventually becoming an elder in the Church of Scotland, and with their help he read agriculture at Edinburgh University, winning the Steven Scholarship and graduating top of his year in 1947.

He was one of the first young scientists to be recruited to the newly-formed National Animal Breeding Genetics and Research Organisation based in Edinburgh, going on to take a PhD and DSc and rising to head of the Department of Physiological Genetics, and deputy director of the organisation, before his formal retirement at 60 in 1986.

During this time he was a leading member of the British Society of Animal Science, and editor for 25 years of its journal Animal Production. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1970.

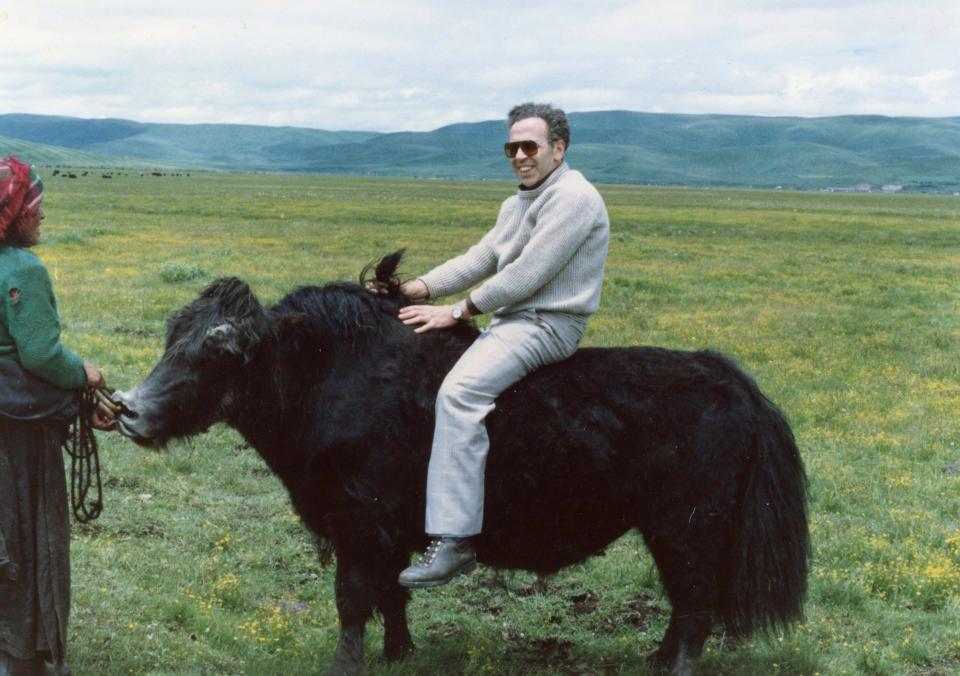

Following his retirement Wiener worked as a consultant for the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation and the British Council in countries including Ethiopia, India and China – where in 1988 he became involved in a project on the yak, which led to the publication of The Yak (2003), one of the few English-language books about the animals, of which he was senior author.

While working in the US, Wiener discovered how his father, who had remarried and begun a new family, had escaped from Germany and made it to San Francisco via Shanghai. They were living in the Shanghai International Settlement when it was occupied by the Japanese the day after Pearl Harbor. Fortunately the Japanese, whatever their other sins, did not share their German ally’s anti-Semitism, ignoring efforts by the Nazi government to repatriate the city’s Jewish community.

For many years Wiener refused to speak German, even to his mother, but his feelings for the country were transformed when he was asked to go back and work for a period at a livestock research station in Mariensee. “We were suddenly with people who genuinely detested the Hitler period,” he recalled. “They were the same as us. I changed my attitude.”

A committed Christian throughout his adult life, Wiener was instrumental in the establishment of the Eric Liddell Centre in Edinburgh, a community centre established in 1980, and at his home in Biggar he helped to establish Biggar and District Community Heritage, a charity which works to improve the local natural environment, chairing it for several years before moving to Inverness in 2008.

Wiener was twice married, secondly to Margaret Russell, who wrote under the pen name Margaret Dunlop and published a biography of her husband, Goodbye Berlin, in 2016. She died in 2020 and Wiener is survived by a son and daughter from his first marriage, which was dissolved.

Gerald Wiener, born April 25 1926, died September 28 2023