Gerth: How a feisty Kentucky bar owner took on a law banning women bartenders – and won

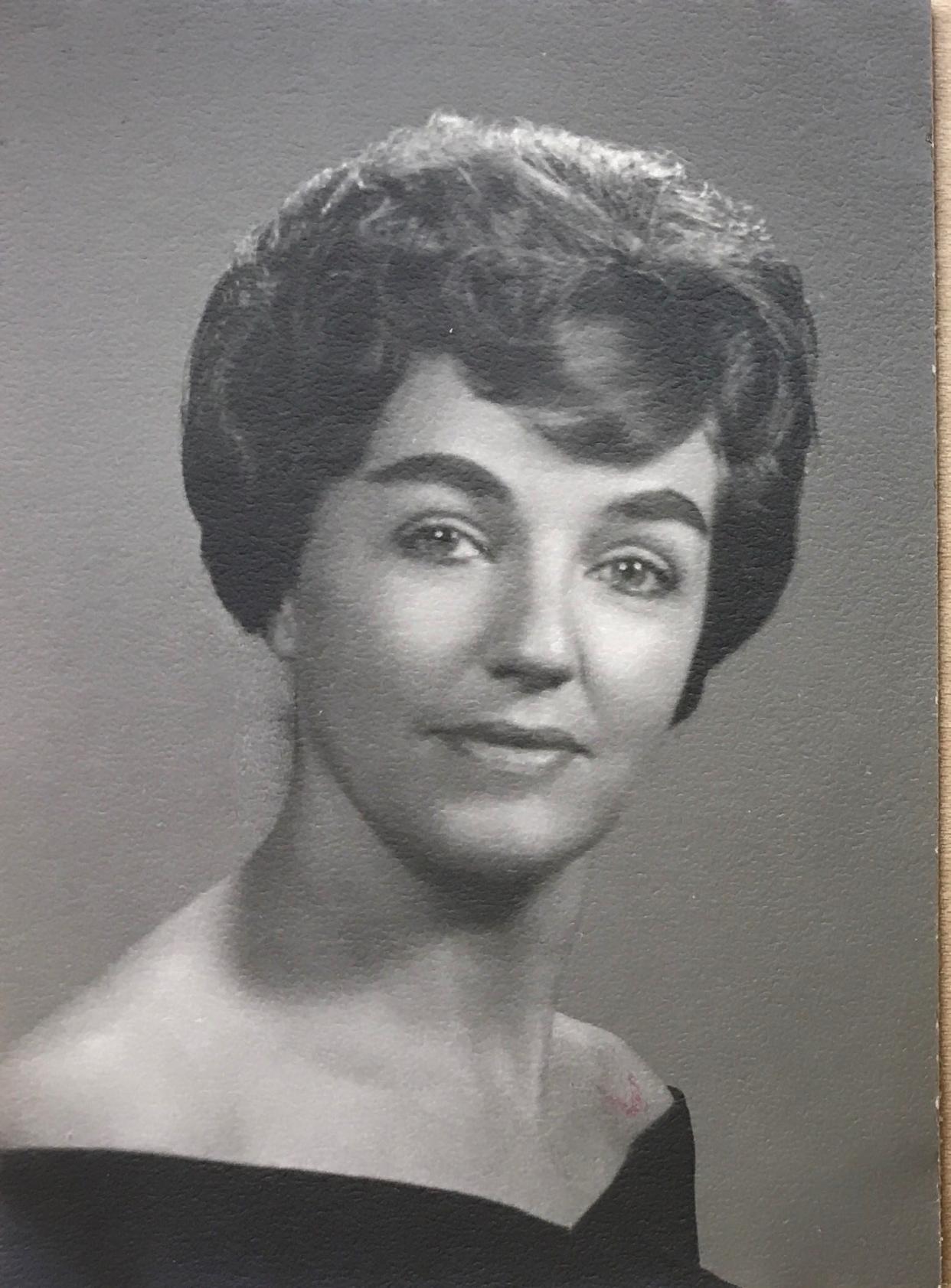

Dixie Demuth was feisty.

She stood about 5-foot-2 − probably less by the time she died three years ago at the age of 102 − and she was always spoiling for a good fight.

When she was a teenager at a one-room schoolhouse in Samuels, Kentucky, she had a run-in with her teacher who expelled her from the school.

The family lore doesn't say what the to-do was over − all they know is how it ended.

Her daughter, Dinah Tichy, has a picture of the teacher, standing next to his glistening new Model A Ford. The note Dixie Demuth scrawled on the back tells the story of how she got her revenge by breaking out all the car's windows.

"Served him right," is the way Dixie summed it up.

"That's when everything connected with me," said Bill Samuels Jr., the chairman emeritus of Maker's Mark Distillery and the third cousin, once removed, of Dixie Demuth, the trouble-making young woman who grew up to own a bar in Louisville and fought to strike down a silly, sexist law that had been on the books in Kentucky for some 200 years.

She's being installed in the Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame for her trail-blazing effort to strike down a law that up until 1972 prohibited women from tending bars − or even being served wine or spirits sitting at a bar.

Until Dixie Demuth came along, women had to be seated at a table to order an old fashioned, a Tom Collins or a cabernet.

Demuth didn't have an easy life. At least not in her younger years.

After the incident at the school in Samuels, her mother packed her off to Nazareth Academy, a boarding school run by the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, near Bardstown. They had their ways to whip incorrigible young girls into shape.

From talking to her family, you get the idea that the nuns failed with Dixie Demuth.

"She was a wild child," Tichy said.

In her youth, the family was pretty wealthy for a while.

Dixie's father ran a country store and had logging interests, and they lived in a home that was called "The Samuels' Mansion." But the Great Depression hit hard.

Dixie's father died, Tichy said. The family lost everything.

Dixie's mother picked up and moved the family, including young Dixie to Louisville. That's where the jobs were.

Eventually, Dixie went to work as a cocktail waitress at Riney's South Seas Bar, a famous local haunt on Muhammad Ali Boulevard (then called Walnut Street) where famed New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin hung out when he came to town for the Derby.

"I knew four locations in Louisville," he once said. "The bar at the Seelbach, the bar at the Kentucky (Hotel), Riney's South Seas Bar and the backstretch at Churchill Downs.

Who knows? Dixie Demuth may have served him drinks.

Over the years, she was married and remarried and remarried and remarried, Tichy said.

"She was, like super attractive," said Samuels.

He joked that she "must have been married a dozen times. ... I can imagine there wasn’t any husband who was going to boss her around too long."

Anyway, Tichy said that sometime in the early 1960s Dixie Demuth got the chance to buy her own bar on Fifth Street, right across from the old Kentucky Hotel, just around the corner from Riney's.

Dixie's Elbow Room was a classy joint.

Tichy said she got married and moved away not too long after her mom opened the bar and she didn't spend all that much time there, but she loved the piano bar, which was in the second floor mezzanine. "I've got the bill from Hubbuch's, who she hired to redecorate the piano bar," she said.

Samuels, who by then had graduated from law school and was working for Maker's Mark, said he was only in the bar a couple of times. "I was advised not to go because I was working for the company at the time and dad (Maker's Mark founder William Samuels Sr.) had ideas where I should go or shouldn’t go."

Classified ads for anything from bartenders to go-go dancers said the bar served an "executive" clientele, but Samuels said it was really the go-to spot for soldiers at Fort Knox who came to the big city for a good time.

"We don't talk about what went on upstairs," Samuels said.

Why not?

"Well, her daughters are still alive," he said.

Tichy said the old law limiting what women could and couldn't do in bars, which dated back to the late 1700s or the early 1800s, always stuck in her mom's craw. Because women couldn't bartend, she said, it meant that they earned about half as much as men.

The law, of course, was suspended when alcohol sales were banned during prohibition. It was brought back four years after prohibition ended.

The Courier-Journal's editorial page mocked the law when it passed in 1938.

"Probably the silliest provision of the new law is that which prohibits women from being served at bars at any time," the paper wrote.

"Women are also 'discriminated against' by the provision which forbids their mixing drinks, or otherwise serving behind bars. They may still serve as waitresses, ushers and cashiers in liquor establishments. This also verges on the ridiculous. If the idea is to remove girls from dangerous proximity to those who drink, why not take them out of saloon jobs altogether."

By the late 1960s, Samuels said the law had made Kentucky a laughingstock since most other states that had similar laws had long since repealed them. Alcoholic Beverage Control officers rarely cited bar owners in Louisville for violating that provision, he said.

But the law still remained on the books.

So in late 1968, a 5-foot-2-inch firebrand named Dixie Demuth decided to poke the bear.

Samuels said she placed a newspaper ad that promised women bartenders.

"Now, the ABC has to do something because she's flaunting the law," Samuels said.

In November, ABC officials raided the joint and charged Dixie with allowing a woman to tend bar and serving a mixed drink to a woman (Dixie's other daughter) who was sitting at the bar. Dixie fought it.

In 1970, a Franklin Circuit judge sided with her, but Shirley Palmer-Ball, the state ABC Commissioner, appealed it to the Kentucky Court of Appeals, then the highest court in the state. Palmer-Ball said he really didn't object to women bartenders but objected to women sitting at the bar.

"It could open the door for prostitutes to sit at the bar," he said.

Two years later, the appeals court ruled in her favor but she was long gone, having moved to Omaha with Tichy's next stepfather.

"She never did anything too exciting in life after that," Tichy said, but she always wanted people to know what she had done.

"She wrote her own obituary," Tichy said. "The thing she wanted mentioned in her obit is she fought that law and won."

Samuels said the thing he regrets most is that his third cousin once removed isn't around for her induction to the Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame. "She would have had so much fun at this ceremony."

Joseph Gerth can be reached at 502-582-4702 or by email at jgerth@courierjournal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: How a bar owner took on a law banning women bartenders – and won