Gerth: Oldham County's favorite son was a racist, and residents are honest about it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What do you do when your most famous resident is the greatest white supremacist filmmaker this side of Leni Reifenstahl?

That’s kind of the dilemma that Oldham County faces.

What the county has decided to do is celebrate the filmmaking abilities of D. W. Griffith, while at the same time acknowledge the difficult part of him — that he was a supporter of the Ku Klux Klan and held beliefs that are flat out wrong.

"History is history. You look at what happened. You have proof and you have records," said Nancy Theiss, the executive director of the Oldham County History Center and an expert on Griffith.

Griffith’s greatest film was undoubtedly “The Birth of a Nation,” his 3-hour silent classic that was released in 1915 and portrayed the Klan as a heroic bunch that protected white women from lecherous Black men and saved Southern society from a complete takeover by African Americans following the American Civil War.

At the same time Griffith was glorifying the KKK for the unthinkable things its members did, he was also pioneering things that would one day become not just commonplace, but critical components of modern-day filmmaking, including the close-up shot, the use of stuntmen, the fadeout and the use of hundreds of extras in such a way that it looked like there were thousands.

Griffith has always intrigued me — at least since the early 1990s when I covered Oldham County for The Courier Journal’s old Neighborhoods section. I’ve always been drawn to people who aren’t all good and aren’t all bad, who have some admirable traits but other traits that are simply reprehensible.

That is Griffith.

Brilliant. But racist.

Film historian Ed Rampell wrote in the Washington Post on the 100th anniversary of “The Birth of a Nation” eight years ago it is “among the most despicable propaganda pictures of all time.”

He’s hardly the first person to suggest that sort of thing.

In fact, the criticism of Griffith isn’t some new-found wokeness.

The film was viewed alternately as brilliant/racist trash since it was released in 1915.

The NAACP protested at its opening at the Liberty Theatre in New York in 1915. Over the next decade, numerous cities banned the showing of the movie or ordered some of the most racist scenes edited out.

By the time Griffith applied for a permit to re-release the film in New York in 1921, one out of every 15 people in the United States had seen the movie and it had earned more than $18 million at the box office.

The following year, as the New York Film Commission considered whether to revoke the film’s permit, one of the commission members wrote that the movie was an “unmistakable attack on the colored race.”

In recommending the permit be rescinded, Joseph Levenson wrote, “As an incitement to crime, the picture is deliberate, well conceived, admirably executed propaganda to inflame the whole gamut of passions of whites against the negroes.“

Let me tell you, if you’re too racist for 1922, well, then, you’re awfully damn racist.

The movie uses racist tropes throughout, whether it’s Black members of the South Carolina legislature sitting barefoot and eating fried chicken on the legislative floor, or a Black man chasing a young white woman who, rather than being defiled by an African American, leaps off a cliff to her death.

The movie shows Black soldiers abusing white citizens and it shows members of the KKK riding to the aid of the poor, helpless white people — at least they were poor helpless white people from Griffith's warped perspective.

It’s generally thought that the movie played a key role in the resurgence of the Klan in that era.

The Indiana Klan, for instance, was formed in 1915 — the same year the movie was released — and by 1925, all but two counties had chapters of the Klan, and more than half the members of the Indiana legislature and Gov. Ed Jackson were all members.

Back home, Griffith was revered.

Theiss said that when he was in LaGrange, he would walk the streets with candy in his pockets to give children. Mothers would dress up their daughters and curl their hair just in case they ran into him — hopeful that the girl would be the next Lillian Gish.

When a new DVD collection of Griffith’s work came out two decades ago, a writer with Slate opined that Griffith maybe wasn’t a racist — in part because one of Griffith's movies involved a love story between a white woman and a Chinese man — because he didn’t have a “coherent political thought in his head” and had only made a movie that reflected the author’s beliefs.

When I mentioned that to Theiss, she got kind of a pained look on her face.

More: Gerth: Queer ducks, transgender deer and the fight over gay pride books in Oldham County

"I think D. W. Griffith knew what he was doing," she said.

In an interview with the Louisville Herald newspaper in 1922, Griffith said, “I am one of those who think that the Northern victory was not a success. I still believe in states rights. I am an ‘unreconstructed Southerner.’”

In an interview with famed director Walter Huston in 1930, Griffith talked about his upbringing and how it impacted the movie. “When you’ve heard your father (who was a Confederate officer) talking about fighting day after day, night after night and having nothing to eat but parched corn, about your mother staying up night after night sewing robes for the Klan …,” he told Huston. “The Klan at that time was needed.”

People have for years struggled with Griffith’s legacy.

In 1945, when a University of Louisville professor recommended the school give Griffith an honorary doctorate degree, President E.W. Jacobson wrote of his concerns. “The impression I get is that he stumbled upon many of the techniques that he first evolved and that he was in no sense an outstanding person.”

They gave him the honorary degree anyway.

In 1953, five years after Griffith's death, the Directors Guild of America named its lifetime achievement award after Griffith. In 1999, it stripped his name from it saying, “the time is right to create a new ultimate honor for film directors that better reflects the sensibilities of our society at this time in our history.”

More: Gerth: Piagentini sure loves secrets. Good thing the judge on his ethics case doesn't

The following year, the organization gave the award to Steven Spielberg, who, being Jewish, would have been a target of the KKK that Griffith so dearly loved.

In 1998, when the American Film Institute released its list of the 100 greatest movies of all time, it included “The Birth of a Nation,” but when it updated the list 10 years later, it had removed that movie and replaced it with another Griffith work – “Intolerance.”

There’s a movement in East Los Angeles now to change the name of the Griffith STEAM Magnet Middle School, a school with 100% minority enrollment named after the racist director.

Back in Oldham County, there’s no attempt to purge Griffith’s name. But there's no attempt to whitewash his legacy either.

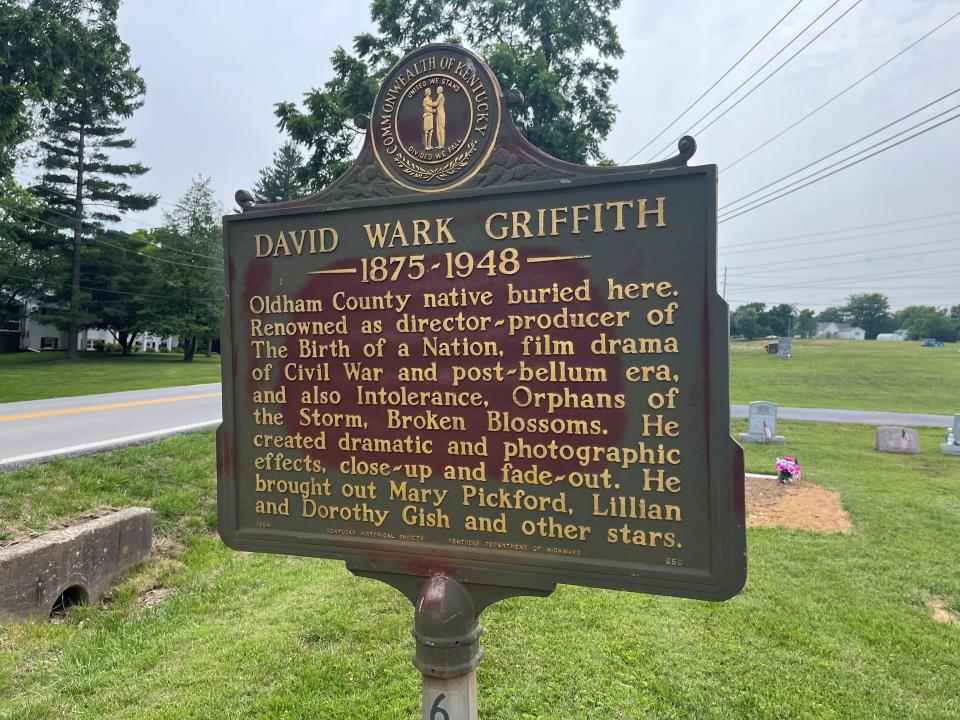

There’s a sign identifying the LaGrange home Griffith built for his mother and where he lived for three years in the 1930s. And there’s a state historical marker outside the Mount Tabor Church Cemetery where he is buried that talks about his accomplishments and even mentions his racist masterpiece.

At the Oldham County Historical Center, a continuous loop of Griffith’s movies plays in a small theater.

But in a nearby display, there's a copy of the playbill people received when they attended the movie, but there's also a copy of “The Clansman,” the racist book upon which “The Birth of a Nation” is based.

The historical center’s website mentions the fact that the Directors Guild of America removed Griffith’s name from its lifetime achievement award and the effort in California to strip his name from the school.

Theiss points out that Griffith wasn't all bad. His movies almost always had a strong female character and he took on issues like abuse and drug addiction at a time when other directors were largely focused on short comedies.

"We try to tell his story we don’t try to make it better or worse," she said.

Joseph Gerth can be reached at 502-582-4702 or by email at jgerth@courierjournal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Oldham County deals with D.W. Griffith's racism honestly