Who gets to vote plays key role in who's elected

Carolyn Krause brings us the second in a series of two columns focusing on the League of Women Voters of Oak Ridge. This one features voting rights.

***

Access to the ballot plays a critical role in the results of elections and the policies that are approved and implemented in a democratic republic like the United States, said Kirsten Widner, a lawyer who teaches constitutional law in the Political Science Department at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

“But shenanigans will always happen,” she added, noting that “state legislatures are infinitely creative in figuring out how to suppress voting by certain groups when they want to.”

As keynote speaker at the League of Women Voters Holiday Luncheon, Widner addressed the history of U.S. voting laws, the mixed record of the U.S. Supreme Court on ballot access, challenges for marginalized groups such as people who had felony convictions who want to vote and initiatives to increase ballot access and protection of voting rights.

Widner, who has a Ph.D. in political science from Emory University and a J.D. degree from the University of San Diego, focuses on how laws and policies that affect marginalized groups are made. She has a particular interest in the political representation of people who do not have or have lost the right to vote, such as Americans with felony convictions. Her forthcoming book “Race, Gender and Representation” will be published by Oxford University.

Why it's important for everyone to vote

It is important for every citizen to vote because “elections matter,” she said. “In the 2020 presidential election, eight of the states were decided in favor of one of the presidential candidates by a margin less than 5% of the vote.

“In the most recent congressional elections in 2022, we saw 40 seats determined by less than 5% of the vote. With the close margins in both the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives, those 40 seats really matter.”

Widner said that “access to the ballot determines who votes, and that’s important because who votes determines who gets elected, which determines political representation and policy outcomes.

“Elections turn on several factors. The quality and experience of candidates matter, whether their views are moderate or extreme matters, their character may matter maybe less.

"Socioeconomic factors such as inflation matter to voters. Social issues like abortion and wokeness are motivating a lot of citizens to vote. Voter turnout matters a lot for elections because voter turnout is driven by voter enthusiasm.”

There has long been a tug of war between those Americans who want to increase access to the ballot and those who react with pushback.

The history of voter access

“The United States does not have a particularly glorious history of voter access,” Widner said. “At the time of the founding of our nation in the 1770s, voting was largely limited to white land-owning men who were at least 21 years old. In the early 1800s states began eliminating those property requirements, but it was still limited to white men.

“In 1870, the 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, giving men of any race the right to vote. Then in 1920 the 19th amendment was ratified, giving women the right to vote.

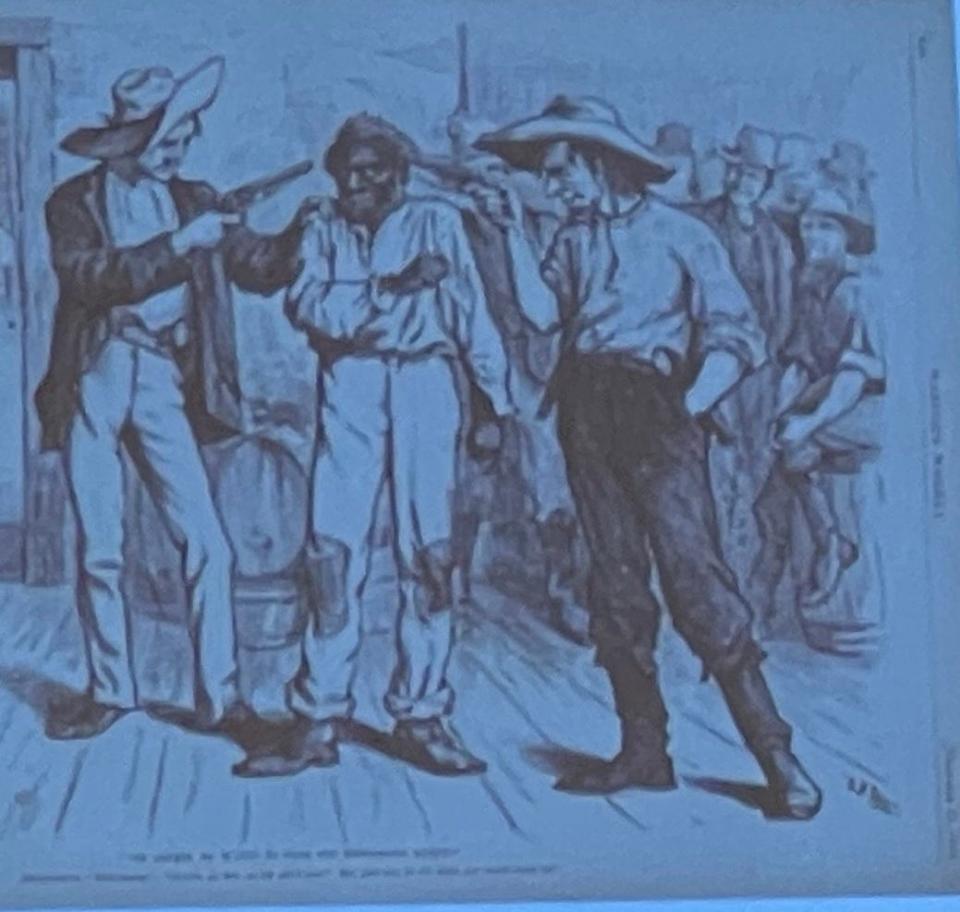

“But this voter expansion did not go smoothly as any resident of the South knows. So, these states used both legal and extralegal means to suppress Black votes, including a whole laundry list that included violence and intimidation, multi-box voting systems (you had to put your ballot for each office in the right box or it wouldn’t get counted), white-only primaries, literacy and understanding tests, poll taxes and grandfather clauses.

“You couldn’t vote unless your grandfather was eligible to vote in 1860, thus excluding the descendants of enslaved people. By 1940, because of these laws and provisions, only 3% of eligible Black voters were registered to vote in the American South.”

In the 1870s Congress did attempt to protect Black voters’ civil rights by passing several acts, but the Supreme Court “did not interpret Congress's enforcement power broadly,” Widner said. In United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the court dismissed the indictments of 96 white voters for intimidating black voters by shooting them. But in Ex parte Yarbrough (1884), the justices upheld federal action against private behavior when the right to vote in national elections was abridged.

In the 1960s, renewed efforts to protect and expand the vote succeeded in 1964 with the ratification of the 24th amendment, which banned poll taxes. In 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act. In 1971, the 26th amendment was ratified, lowering the voting age to 18.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Supreme Court “was moving in the same direction as the country,” Widner said. In Baker v. Carr (1962), she noted, “the court decided that it can weigh in on gerrymandering cases.” Gerrymandering is the manipulation by a state legislature of an electoral constituency’s boundaries to favor one party or race in elections to Congress, for example.

In Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the court established the principle of one person one vote. In Louisiana v. U.S. (1965), the court struck down Louisiana's “understanding test,” which permitted local voting officials to reject a voter's registration if the person didn't show a sufficient understanding of the state and federal constitutions.

In South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966), the Supreme Court upheld the preclearance requirements of the Voting Rights Act, meaning that a proposed law must not have the purpose or effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race, color or membership in a language minority group. In Dunn v. Blumstein (1972), the court struck down a residency requirement of one year, holding that 30 days is sufficient to ensure that only residents vote.

Black voter access and registration expanded during the Civil Rights Era in the 1960s, and the expansion of voter access continued into the 1990s, according to Widner. She gave these examples in her slides and talk:

“In 1980, California became the first state to enact no-excuse absentee voting. In the 1980s and 1990s, states began embracing early voting in person. In 1990, Oregon became the first state to have all ballots issued by mail. In 1993, Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act, requiring participating states to make voter registration available at Departments of Motor Vehicles, by mail-in application and at state public assistance and disability offices.

“Today, all but three states offer early in-person voting; the exceptions are New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Alabama. Percentages of early voters in 2012 North Carolina elections were 64% Blacks and 49% whites. Eight states have all mail voting, and another 35 states and the District of Columbia allow no-excuse absentee voting. However, 15 states, including Tennessee, require an excuse to vote absentee.”

Widner called the 2000s “a time of retrenchment” in which many states adopted strict voter ID laws that were upheld by the Supreme Court in 2008. Five years later, the preclearance formula of the Voting Rights Act was invalidated by the highest court in the Shelby County v. Holder case. This ruling accelerated moves to adopt restrictive practices such as voter registration purges, elimination of polling places and the reduction of early voting opportunities.

In Tennessee and 10 other states, a photo ID is required, and additional steps are required for a voters to cast ballots if they lack a required photo ID.

In the past few years, Widner said, the Supreme Court has further narrowed remedies for voting rights violations and limited Voting Rights Act challenges in cases where the state provides more voting opportunities than it did in 1982, when the act was last amended.

Widner said legislative efforts are underway to limit ballot harvesting in which a third party gathers and submits completed absentee or mail-in voter ballots completed by disabled and other people. Some legislatures are trying to limit voting on college campuses because college students are disproportionately liberal. Tennessee legislators are considering a proposal to fingerprint voters.

Positive news for voters

Widner delivered news about this year’s Supreme Court decisions that are positive for voters. In Allen v. Milligan (2023), the court struck down racially gerrymandered maps that created only one majority-minority district, suggesting the state should have just two such districts. Alabama refused, she said, and created another map that did not solve the problem. A lower court struck down the new Alabama map and the Supreme Court denied Alabama an emergency stay. The lower court adopted a new map drawn by a special master.

In Moore v. Harper (2023), the Supreme Court rejected the independent state legislature theory and held that the federal elections clause does not vest exclusive and independent authority in state legislatures to set the rules regarding federal elections. Thus, state Supreme Court reviews of voting maps are not barred.

Efforts to expand voting

Widner cited current efforts to expand voting. In some states, people with felony convictions are re enfranchised, but they find it difficult to pay court fines and fees and win restitution as conditions to get back the right to vote in elections. She noted there are efforts to get voting access for people in jails awaiting trial because none of them have been convicted of a crime.

Local movements, she added, are underway to lower the voting age to 16 so high school students can vote for or against local school board candidates who propose curriculum changes and on other issues affecting teens and their futures.

California now allows ranked choice voting in which voters rank candidates in order of preference. This fastest-growing nonpartisan voting reform promises better choices, better campaigns and better representation.

***

Thank you Carolyn, voting rights are important for all of us and the assurance that all who want to vote can vote is a vital part of our republic.

D. Ray Smith is the historian for the city of Oak Ridge. His "Historically Speaking" columns are published weekly in The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Who gets to vote plays key role in who's elected