Getting ‘forever chemicals’ out of your tap water could increase rates for KY residents

Some utilities in Kentucky would likely have to upgrade treatment plants or processes to comply with a federal proposal aimed at reducing suspected cancer-causing chemicals in drinking water, which could mean rate increases for residents.

The chemicals are called per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is in the process of putting the first enforceable limits on six of the chemicals.

For two of the most common ones, called PFOA and PFOS, the proposed limit in drinking water would be 4 parts per trillion (ppt).

Some Kentucky water systems would have to change treatment methods or install new filter systems to meet that limit if it goes through as the EPA proposed.

Many utilities could not absorb all the cost of making upgrades, so EPA’s proposal is likely to contribute to rate increases in some places.

Some “water rates are going to go up” in order to deal with the rule, said Annette DuPont-Ewing, executive director of the Kentucky Municipal Utilities Association, which represents city-owned utilities.

EPA expects to finalize the rule by the end of the year.

The agency could change parts of the proposal as it considers comments from utilities, business and environmental groups and citizens.

But officials with water systems in Kentucky said the agency likely won’t back away from the drive to limit the most common PFAS chemicals to 4 parts per trillion because of concerns the chemicals can harm health at very low levels.

“EPA is pushing hard on this,” said Mike Gardner, water and sewer systems manager for Bowling Green Municipal Utilities.

The level of 4 ppt would be equivalent to four grains of sand in a Olympic-sized swimming pool, according to information on the Bowling Green Municipal Utilities site.

Testing has not detected PFAS chemicals in Bowling Green’s water.

The rule would give utilities time to meet the mandate, and Congress has approved billions in funding to help with the costs, but it won’t cover all costs nationwide.

What are PFAS and why might they be dangerous?

The proposed limit of 4 parts per trillion (ppt) sounds low, but EPA set a goal of removing all the chemicals from water, an indication the agency considers no level completely safe.

Concern over PFAS chemicals has been growing in recent years as evidence mounted about their potential health threats.

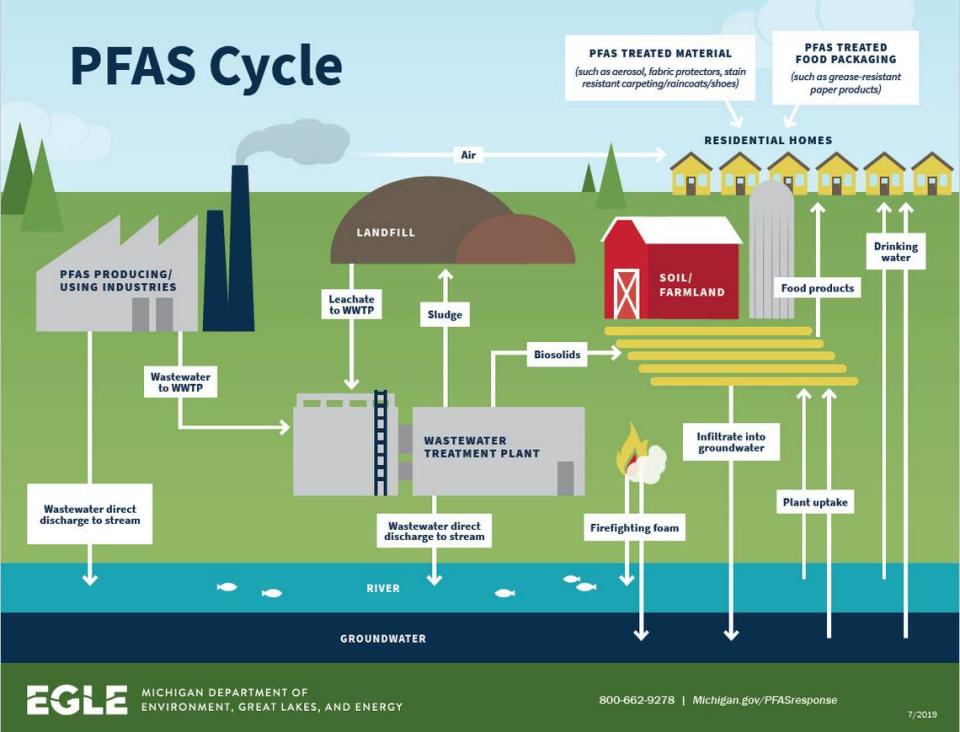

The chemicals, which have been around for decades, are useful because they repel grease, oil and water. They’ve been used in a wide range of products, including firefighting foam, non-stick cookware, stain-resistant carpet, furniture, cosmetics, dental floss and fast-food wrappers.

Most people have been exposed to them because there are so many sources.

The chemicals don’t break down quickly in the environment. That’s why they’ve been called “forever chemicals.”

The EPA and other agencies say exposure to the chemicals may cause a number of health problems, including decreased fertility; increased blood pressure among pregnant women; developmental delays in children; increased cholesterol; higher risk of obesity; a reduction in the immune system; and increased risk of some types of cancer, including kidney cancer.

The Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet issued an advisory last year for people to limit eating fish from state waterways because of the presence of PFAS.

The chemicals can accumulate in the body over time, which is why the EPA is moving to reduce exposure by getting PFAS out of drinking water.

“Optimally the goal is zero. We want to protect our customers, absolutely,” said Mark Julian, manager of the City of Maysville Water & Sewer Department. “We know that any of this stuff is not good.”

EPA said in its analysis that when the new rule is fully implemented, which could take several years, it “will prevent thousands of deaths and reduce tens of thousands of serious PFAS-attributable illnesses.”

What PFAS data shows

The cost to limit PFAS in drinking water will vary based on a number of factors, including the level of the chemicals in water sources — such as the Kentucky and Ohio rivers — and whether treatment plants would need to add equipment or change methods for purifying water.

“If the particular utility is downstream of certain industrial facilities, or downstream of military or commercial airfields there is a possibility they will need additional treatment systems,” DuPont-Ewing said. “It all depends on the source water (whether surface or groundwater) and what the possible sources of PFAS are upstream or upgradient from the utility’s intake.”

Some water systems in Kentucky won’t have to make changes to meet the proposed PFAS limit because the chemicals are not in their source waters.

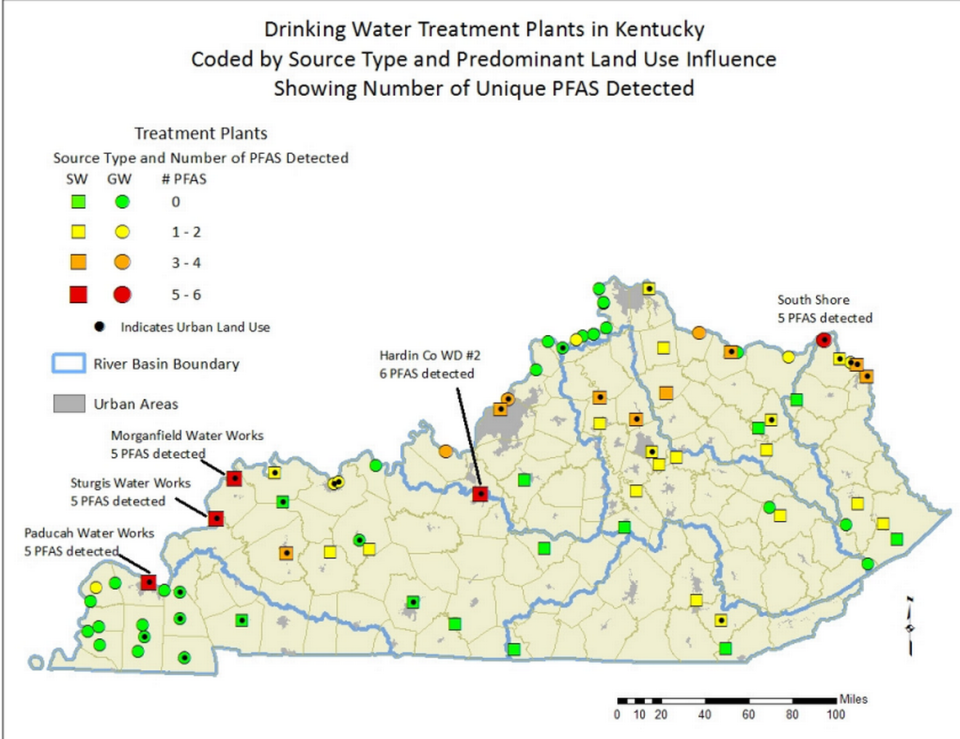

Testing has shown varying levels of PFAS at water treatment plants around Kentucky.

In 2019, the state Division of Water analyzed water at 81 of the 200-plus treatment plants in the state to get an initial picture of PFAS contamination.

The tests detected at least one type of PFAS chemical at 41 of the 81 plants, and found levels at or above 4 ppt at more than a dozen plants, including in Louisville, Maysville, Ashland, Georgetown, Owensboro and Paducah.

The highest level of one chemical detected in the state, PFOA, was 23.2 ppt at South Shore, in northeastern Kentucky.

Plants that used the Ohio River as a source of raw water had the highest number of detections, followed by plants that draw from the Kentucky River.

The 2019 tests detected PFAS chemicals at two of the Kentucky American Water treatment plants serving Lexington, though the levels were below the new, proposed limit of 4 ppt.

The levels of PFAS chemicals can change, however.

In 2021 tests, there were no PFAS chemicals detected at the Kentucky American treatment plant on the Kentucky River where they had been found two years earlier.

The 2019 and 2021 tests detected PFAS chemicals at Kentucky American’s Richmond Road plant, which draws water from the Jacobson Reservoir, at levels below 4 ppt.

Kentucky American is evaluating the EPA’s proposal on limiting PFAS chemicals, company spokeswoman Susan Lancho said in a statement.

“As always, American Water supports the U.S. EPA’s efforts to protect the quality of drinking water and our annual Water Quality Reports show our commitment to protecting our customers and the communities we serve by meeting or surpassing required federal, state and local drinking water standards,” Lancho said.

The 2019 testing detected four different PFAS chemicals in the water supply for Georgetown, but only one, PFOS, was above 4 ppt. The level detected was 5.46 ppt, according to the state results.

More recent testing in 2023 by the Georgetown Municipal Water and Sewer Service (GMWSS) detected three PFAS chemicals, but all were below 4 parts per trillion, said Chase Azevedo, general manager for the utility.

Compliance will be based on four quarters of tests, however, Azevedo said.

“Three more quarters of sampling will be required before GMWSS can calculate whether we are in compliance or not,” Azevedo said.

The utility will make decisions on how to deal with PFAS after more tests, he said.

The utility included funding in a rate study to deal with changes if EPA designated PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances, so it does not anticipate an increase in rates specifically to deal with the proposed PFAS limit, Azevedo said.

At the Maysville water plant, the 2019 tests by the state Division of Water detected PFOA at a level of 5.09 ppt, but additional testing so far this year did not detect any PFAS chemicals above the proposed limit of 4 ppt, Julian said.

The levels could be higher in future tests, however.

“It’s promising but it could change,” Julian said.

Julian said the Maysville water plant would need to make changes, such as adding granulated activated carbon filters, if EPA finalizes a limit of 4 ppt on PFAS chemicals.

The new rule would also potentially bring costs to dispose of PFAS waste.

Costs likely coming for Kentucky

Several water-system managers said investments were needed even before the EPA proposal on PFAS chemicals in order to replace aging infrastructure and cover the rising costs of chemicals and labor.

Kentucky generally has less of a problem with the chemicals than many other states, said Arianna Lageman, compliance specialist with the Kentucky Rural Water Association.

Still, it is evident that the EPA rule would mean higher costs for many systems, pointing up a need for greater federal and state assistance, water-system operators said.

The changes to remove PFAS chemicals could be as simple as adding more powered carbon to the water, or they could involve having to install expensive filtration systems.

But there is a cost for any change to deal with the chemicals.

“It’s safe to assume that Kentucky utilities are on the verge of spending hundreds of millions of dollars in order to comply with the new rule,” Lageman said.