Gettysburg 160th anniversary offers chance to learn about York County Civil War story

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

.

A couple of years ago, historian Scott Mingus and I pulled together a list of unsung or overlooked York County Civil War sites.

This is a good moment to share part of our list — on the eve of the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. Every five years since the battle, interest in the Civil War heightens in this region, and this is one of those anniversary years.

Some of these sites were marked by Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Pennsylvania campaign in the summer of 1863, particularly when Gen. Jubal Early’s 6,600-man Confederate division overran largely undefended York County, followed a few days later by more than 4,500 cavalrymen under Gen. Jeb Stuart.

A little history before we dive into our list of unsung sites:

York’s fathers sought out Early’s invaders in Abbottstown and formally surrendered the town hours later at a farmhouse in the village of Farmers, 10 miles from York. The Confederates entered York on June 28, 1863, and occupied it for two days, persistently prying goods and money from residents.

Gen. John B. Gordon’s brigade marched on to Wrightsville in an attempt to capture the Susquehanna River bridge but forces under Union command torched the structure to stop the rebel advance.

On June 29, Lee recalled Early’s division, which countermarched the next morning toward Gettysburg, where it sustained heavy casualties in fighting on Cemetery Hill on July 2.

On June 30, Stuart’s cavalry slammed into Union Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s column on the streets of Hanover. More than 300 casualties — dead, missing and wounded — resulted.

But York County’s involving in the Civil War was much more than this fighting and the marching in these days before Gettysburg.

After the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter in 1861, York County units served as early Union responders in guarding bridges on the Northern Central Railway.

The York Fairgrounds, then southeast of King and Queen streets near today’s Royal Square, was converted into a boot camp for green Union recruits early in the war.

York’s Penn Common became the site of Yankee cavalry barracks and then a major Union Civil War hospital.

And the human toll was immense. More than 600 documented county residents died in the conflict.

There is, indeed, a lot to York County’s Civil War story.

To learn more about that history, how can you visit some sites, by car or foot?

Here is a sampling, presented in threes. With phone in hand, follow the links from the following story and you’ll find an expanded version about the historic area you are visiting: https://tinyurl.com/mrye87m8.

3 city sites

Not all unsung sites lay in remote places.

A site with great meaning stood in the heart of York. This patch of ground hosted a 110-foot flagpole that stood tall in the center of Centre Square, today Continental Square, in May 1861.

This pole of pine played a support role to a 35-foot American flag. It was that banner the Confederates brigade under Gordon’s command lowered after they freely marched into York’s square under the surrender terms. But the flagless pole towered above the invaders in their two-day occupation, tall and straight.

After taking in the square, move a block east on East Market Street. Stand on the steps of the old Lafayette Club, now York College’s Center for Community Engagement. You’ll be in the place that Gordon, astride his horse on the nearby street, engaged with the family of leading businessman P.A. Small. He assured them that no harm would come at the hands of his soldiers, an assurance he did not grant to the townspeople of Wrightsville as he lobbed cannonballs at and above the town at the bridge.

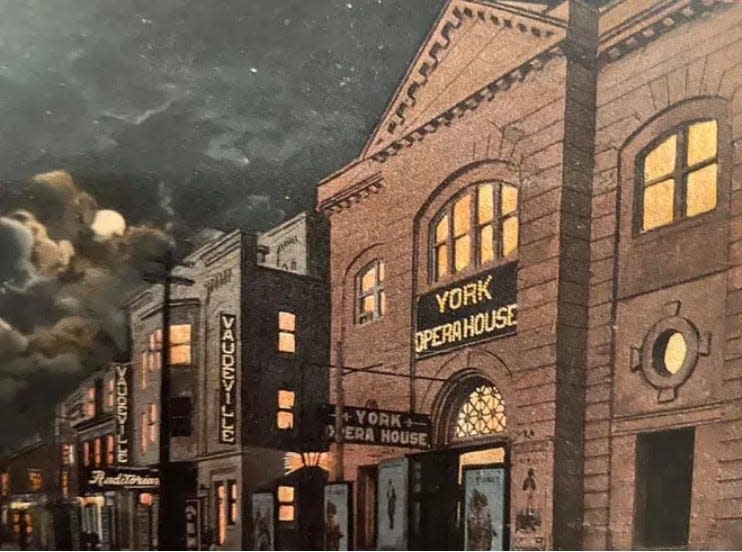

To follow the Gordon storyline, walk up to the old telephone company on South Beaver Street. It replaced the York Opera House, where Gordon received a hero’s welcome from York residents 30 years after the war ended. Curiously, York granted happy honors to a man who stole horses, trampled crops and terrified residents in his march across York County to the Susquehanna.

3 Underground Railroad sites

The Goodridge Freedom Center, a museum on East Philadelphia Street, and Willis House, a privately owned brick structure on Manchester Township’s Willis Lane, have passed muster as Underground Railroad sites with the National Park Services National Register of Historic Places and Gateway to Freedom.

After the war, noted historian William Still named the Willis House as a place of refuge for freedom seekers. The Goodridge house, former home of freedman and leading York businessman William C. Goodridge, operates as a museum exploring the Underground Railroad and early American photography.

The long-gone home of Samuel Berry, a Black Underground Railroad station master, lies under Interstate 83, south of Shrewsbury.

Several miles north on the Susquehanna Trail, a state historical marker tells the Berry story atop the south hill in Shrewsbury.

3 markers remember invaders

There’s a grave of an unknown Confederate on Hellam Township’s River Road a mile north of Accomac Inn. It’s not known how his body got there. The common conjectures are that he was an enemy spy or possibly his body washed downstream from an engagement in northern York County.

There’s also a Confederate grave marker in Prospect Hill Cemetery near the office designating five Confederates who died from wounds suffered at Gettysburg.

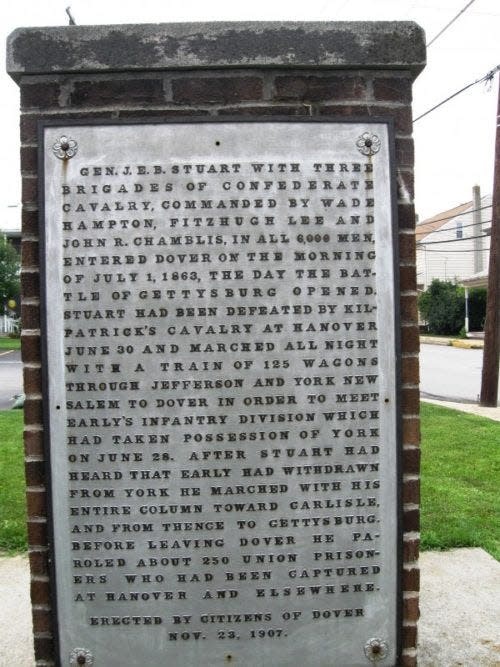

A third marker — a plaque — detailing Stuart’s invasion of Dover is mounted in the lawn at the Dover firehall, Canal Road. About 4,000 county residents showed up for the plaque presentation in 1907. A speaker at the dedication said the plaque was not to glorify the invaders but to remind residents and visitors that war had visited Dover.

3 sites honoring Black soldiers

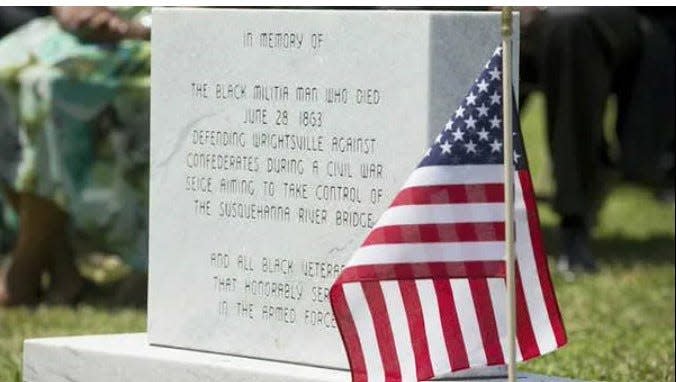

A decade ago, a successful campaign commenced to place a headstone in Mount Pisgah Cemetery on Wrightsville’s Mulberry Street to honor an unknown Black man who died in the trenches in the Battle of Wrightsville. He was the only fighting man to die on either side.

In historically Black Lebanon Cemetery in North York, about 35 Civil War soldiers are laid to rest, including the Rev. John Hector.

A building in Royal Square housing The Parliament Arts Organization, 116 E. King St., served as home to Hector. He was a U.S. Colored Troops veteran who later served as a pastor in the AME denomination and became widely known as a touring speaker advocating for Prohibition and Union veterans rights.

3 sites to stop and ponder

Here are three examples of general places to pull off and ponder — the exact sites are gone or unknown.

Horse Thief Lane in West Manheim Township is a site tireless researcher Richard Resh has identified as a refuge for farm horses when Confederates raided the county before Gettysburg. This road runs off Baltimore Pike, south of Hanover and is on private property.

The Detters Mill area in western York County was the scene in which six men lynched a Black man, who might have been with those Confederate raiders known for their thievery of horses. But we’ll never know because they meted out their deadly version of justice with their trigger fingers. This site is in the vicinity of Harmony Grove Road in Warrington Township.

And Emig’s Grove near Manchester was a Christian camp meeting site where an unknown Union soldier was buried and largely forgotten.

The campground, today’s Penn Grove Retreat, relocated to southwestern York County after a fire, leaving the soldier’s gravesite behind. The original Emig’s Grove operated near Forge Hill Road, now private property.

3 Hanover sites

Hanover is blessed with about 20 wayside markers explaining the Civil War era.

Here are descriptions of three on Frederick Street, as found on Main Street Hanover’s site:

“After disengaging from the Union cavalry in the late afternoon of June 30, Confederate Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry division left Hanover. Stuart and his men embarked upon a half-circle odyssey south then northeast around town while Stuart's rear guard, did not depart Hanover until after dark.”

“In 1863, charming brick and wooden homes lined both sides of Frederick Street from Center Square to the Winebrenner Tannery and the Karl Forney Farm. This ... became the turbulent center of confusion during the battle as cavalrymen from New York and Pennsylvania fight face.-to-face against those from North Carolina and Virginia.”

“In many towns like Hanover, rail depots also were telegraph headquarters. Hanover's was on present-day Railroad Street. Three days before the Battle of Hanover, Confederate Lt. Col. Elijah White's men were on a mission: search for and destroy.”

3 York monuments

These Civil War monuments might be known by some people, but they’re included here in case they’re new to you.

The Soldiers & Sailors monument stands in Penn Park, an 1890s exclamation point to park improvements making it a showpiece for the newly minted city of York. Something has been missing from this scene for about a decade: Cannons that stood around the monument for many years now can be seen on the lawn of Hanover Junction station, an interesting rail trail stop that tells about Abraham Lincoln’s visit there and other moments.

Soldiers Circle in Prospect Hill Cemetery marks the burial spot of Union soldiers who died in the military hospital that operated on the site where the Soldiers & Sailors monument stands.

The monument in Salem Square in the city’s west end honors the York Rifles, a unit that had continuity from Revolutionary War to the Civil War.

Plus 1

For a closeup look at the bridgeless stone piers that supported the Susquehanna River span that was burned, check out the grassy area north of Columbia Crossing in Columbia, Lancaster County.

Learning lessons for today

You could say that learning about history goes beyond books, videos and other media. If you’re able, consider learning about York County history via vehicle or walking.

There’s just something compelling about exploring actual historic sites in search of meaning. And learning lessons for today.

Sources: Parts of this were adapted from a presentation prepared by Jim McClure and Scott Mingus. McClure will present on this topic, titled “Discovering York County’s Lost Underground Railroad and Civil War Sites,” at 10 a.m. June 24, at the Wrightsville Historical Museum as part of the Riverfest weekend.

Upcoming presentations

Other talks by Jim McClure in June:

“Telling York County’s Full Civil War Story … At Last,” 7 p.m. June 21, York Civil War Roundtable, York County History Center.

“Spanning the Susquehanna: The Bridge that Burned and Other River Bridges,” 5 p.m. June 25, John Wright Restaurant lawn, Wrightsville. Part of the Riverfest weekend.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

More: There are no Confederate memorials in York County, but ...

More: A black Civil War volunteer's heroism, and how his deeds in Wrightsville came to be recognized

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Gettysburg 160th anniversary: learn about York County Civil War story