As Ghislaine Maxwell’s family is escorted into the courthouse, an accuser waits in the cold

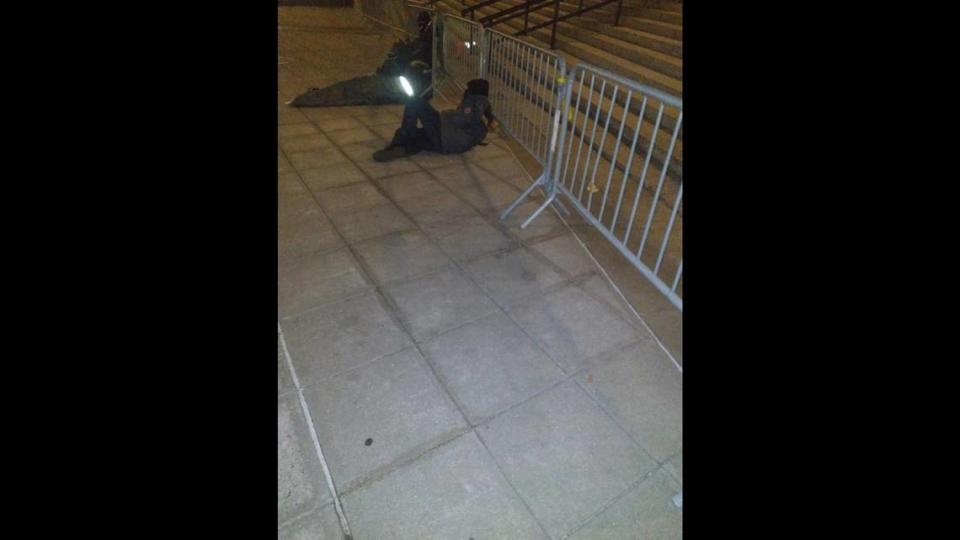

The line at the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse in lower Manhattan begins in the dead cold of night, with a handful of men, shivering under blankets or umbrellas, huddling sometimes in a nearby parked car to keep warm in the wee hours of the morning.

The line-sitters, as they are called, earn $30 to $50 an hour for holding a place in line from 2 to 7 a.m. for those who can afford it — mostly journalists, but some members of the public — to guarantee themselves a seat in the courtroom where British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell is on trial, charged with sexual trafficking. The jury is presently deliberating her fate.

Liz Stein can’t afford a line-sitter, so she waits in line almost every day.

Her day begins at 4 a.m.

She takes a two-hour Greyhound bus ride from her home in Center City, Philadelphia, to the bus depot in midtown Manhattan. She then takes the subway to downtown and walks to Foley Square to wait in front of the courthouse, often in the bitter wind, her feet numb, along with everyone else. At the end of the day, she makes the same two-hour trip back home.

As deliberations potentially stretch into new year, Ghislaine Maxwell begins to court media

On a good day, the line at the courthouse is short, and she gets into the main courtroom with no questions asked.

[Editor’s note: on Wednesday, one day after the original publication of this story, Stein had no success. She was denied entry and told by a U.S. Marshal that no seats had been set aside in the court for victims. Several reporters offered their seats up to Stein, but were told they could not. When Stein later contacted Joseph Pecorino, who manages access to the court, she said he screamed at her.

“He screamed at me and said that I was not a victim,” Stein said.

The denial comes on the day some court observers anticipated that the jury would deliver a verdict in the courtroom. Edward Friedland, the district executive for the court, said that multiple seats have been set aside in the courtroom each day for victims, but that the U.S. Attorney’s office is responsible for sending over the names of victims to fill the seats.]

On this day, Stein, 48, is dressed impeccably, wearing a bright pink wool coat on top of a blazer, a black skirt and practical shoes; there is often a strand of pearls or a delicate gold locket around her neck.

She sits in the overflow gallery, a backpack at her feet. Inside, are two Victoria’s Secret nightgowns and a black Escada ball gown. She says these items were given to her more than two decades ago by Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein, a vivid and painful reminder of the sexual assaults she says she suffered as a 21-year-old college student.

Maxwell is accused of procuring women, some of them underage, for her boyfriend Epstein, and sometimes participating in sexual abuse.

The court’s hierarchy, which gives priority seating to Maxwell’s family in the front row of the main courtroom, then to New York-based media and law enforcement, has not guaranteed Stein or other accusers a place in the main courtroom. Most of them have been relegated to overflow courtrooms on other floors, with a video screen showing a fraction of the main courtroom. The audio is not always reliable, and at times, it’s difficult to know which lawyer is speaking, since not all of them are on camera.

“We have to wait and wait to get in the back row of an overflow courtroom — and Maxwell’s sister and brothers are ushered into the courtroom every day like royalty,” Stein said. “It’s hard to understand why the family of an accused sex abuser gets a front-row seat when the victims can’t even get into the courtroom.”

Sarah Ransome, a South African-born woman who said she was abused by Epstein at the age of 22, arrived at the court on the first day of Maxwell’’s trial and told the Herald she was “appalled” that she and other accusers hadn’t been granted special access and had to wait in long security lines in the cold along with the rest of the public.

Ransome’s attorney, Robert Y. Lewis, said that he had contacted the U.S. Attorney’s Office months before the trial and had initially been told by Wendy Olsen Clancy, the victim/witness coordinator, that Ransome didn’t qualify as a victim.

That despite the fact that Ransome, now 37, had spoken at a New York hearing alongside other Epstein accusers weeks after he was found dead in a Manhattan correctional facility on Aug. 10, 2019.

Although Epstein is suspected of abusing scores of women, the trial in Manhattan involves only four of them.

(Generally, in a court setting, witnesses are not allowed to sit in the courtroom and hear others testify, to avoid accounts being tailored to match the stories of others. None of the accusers have been sitting in the gallery after they testified.)

Finally, Lewis contacted U.S. District the Judge, Alison Nathan, who is presiding over the trial to ask about access. On Oct. 14, Nathan issued an order directing accusers to contact Olsen’s office and the court’s administrator, Joseph Pecorino, about securing access to the trial.

Ransome eventually qualified as a victim and was given the choice to attend one of two days in a reserved seat in the courtroom: Closing arguments or the next day of the trial. She opted to attend the closing arguments.

Pecorino and the U.S. attorney’s office played a game of hot potato when asked how many seats had been set aside in the courtroom for Maxwell’s family and for accusers, or what the criteria was for determining who qualified as a victim and who did not. They ultimately did not provide answers to any of the questions. Olsen did not respond to a request for information either.

The Epstein/Maxwell story, chronicled in a Miami Herald series called Perversion of Justice, has always been about power and money — how it corrupts — and how the privileged few are able to live by a different set of rules in the criminal justice system.

In the eyes of Stein and Ransome, the New York trial is yet another bitter example of how Epstein’s and Maxwell’s accusers remain invisible, shuffled aside, and ignored, much like they were two decades ago when prosecutors in South Florida gave Epstein a secret plea deal without telling those he was accused of abusing. Epstein, in his 50s at the time, was accused in 2005-2007 of sexually abusing dozens of middle and high school girls at his Palm Beach mansion.

Federal prosecutors quietly negotiated the lenient plea deal with the powerful, politically connected financier, allowing him to plead guilty to minor prostitution charges. He served 13 months in the county jail, most of it under a work-release program where he spent little time actually behind bars.

A federal judge later ruled that the deal was illegally kept from Epstein’s victims, and that prosecutors misled some of them into believing they were still actively pursuing the investigation when in reality they had disposed of the case.

Epstein’s accusers felt further betrayed by the courts, where judges often sealed or redacted key documents so that no one would know the extent of Epstein’s crimes — or who was involved. The FBI case file has never been made public.

Epstein was again arrested — this time by New York federal prosecutors in July 2019. But he died a month later while awaiting trial on sex-trafficking charges. His death was ruled a suicide by hanging.

Maxwell, 60, had long been suspected of helping Epstein, and was indicted a year later. She faces six criminal counts related to aiding Epstein’s abuse of girls between 1994 and 2004.

Stein says she met Maxwell in the fall of 1994 as a senior at the Fashion Institute of Technology. At the time, she was working an internship at Henri Bendel, a luxury women’s retailer on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. One day, Maxwell came into the store and introduced herself to Stein.

“We hit it off immediately, she was very engaging — which is something we’ve heard from other victims,” she said.

Several other women have claimed that they were attending the Fashion Institute of Technology — or hoped to attend — when they met Epstein and Maxwell. Ransome was among them.

Stein, who is 4-foot-11 and weighed about 80 pounds back in 1994, looked years younger than her 21 years.

It wasn’t unusual for Stein to deliver packages to some of the store’s high-end clients.

“I called Maxwell’s office to arrange the delivery of her items, and I was instructed to bring them to a hotel in midtown Manhattan. When I got to the hotel, I went to drop them off at the concierge, but was told to take them into the bar, where she was sitting with Jeffrey Epstein.”

They expressed interest in her fashion career and invited her to their room.

“It was the first time they assaulted me,” Stein said.

“They were dazzling. They made me feel like there was no one else in the universe but me.”

She was abused by them off and on for three years, she said. But she kept what happened secret, feeling ashamed and blaming herself.

“These are secrets I kept for decades and couldn’t tell anyone. When Epstein was arrested and all over the news, I realized that it wasn’t just me. That’s part of the shame — you think these things just happened to you.

“I was sickened to find out how many more women this happened to...what keeps coming up about the culture of silence is so incredibly true. The emotional manipulation is just not something that you can describe to someone — it’s not anything that makes any kind of rational sense — it’s a fear that you still have decades later,” Stein said.

They promised to connect her with the right people in the fashion industry — but it came with a price.

“I reeled in the aftermath of what happened for decades afterwards. It altered the course of my life,” Stein wrote to the U.S. attorney’s victim coordinator on Nov. 23, almost a week before the trial. “Attending this trial is extremely important to me to finally have closure. As a victim, I appreciate your help and understanding in helping those of us who want to attend these proceedings in person.”

The next day, she received a terse response from Wendy Olsen, the coordinator.

Ms Stein

You have to take a chance and see if you can get a seat in the overflow courtroom.

You are not listed as a victim and therefore I cannot assist you.

Wendy Olsen

“I think it’s horrible. It’s horrible. Anyone who is a victim of this crime needs be treated with at least the same respect as the defendant’s family — at least the same respect,” Stein said.

Part of the limited seating in the courtroom has to do with the social distancing because of the pandemic. There are only a certain number of seats available in each courtroom, and in the early days of the trial, three or more overflow courtrooms were set up to handle the overflow crowd. It was chaotic, however, in the first weeks of the case — and accusers have attended less and less.

Both Stein and Ransome were told that they didn’t make the list of “victims,” but it was never explained to them what they had to do to get on a list. (Stein also wasn’t approved to receive compensation from the victims’ fund set up by Epstein’s estate.)

Stein usually enters the main courtroom quietly, so as to not be noticed by court officers. She has been questioned at times about why she is there and whether she is on the “list.” When she does get in, she often sits behind Maxwell’s sister, Isabel, in the front row.

Maxwell, like everyone in the courtroom, must wear a mask, so only her eyes are visible. Stein notices little things in her body language that she remembers, like the way Maxwell, who sometimes turns around to make eye contact with her relatives, uses her hand to push her hair from her face.

“It helps me to look her in the eyes and not be afraid. That’s been worth it,” Stein said.

But listening to the accusers in the case tell their stories of how they were allegedly groomed, manipulated and abused by Epstein and Maxwell has been difficult to hear.

She worries that jurors will not understand why the women continued to associate with Epstein and Maxwell after they were allegedly assaulted.

“It’s difficult because these jurors are just having to judge this case solely on the witnesses that were presented and the testimony they have. They’ve seen four women with very similar but different stories. It does sound hard to believe. Who would believe it? That’s why a lot of us didn’t say anything — because who would believe it? It wasn’t that simple to just get away.’’

[Editor’s note: on Wednesday, one day after the original publication of this story, Stein had no success. She was denied entry and told by a U.S. Marshal that no seats had been set aside in the court for victims. Several reporters offered their seats up to Stein, but were told they could not. The denial came on the day many court observers anticipated that the jury would deliver a verdict in the courtroom. Pecorino offered no explanation for Stein’s denial and why no seats had been set aside for victims. Judge Nathan couldn’t immediately be reached for comment.]