Giant sequoias burned because of humans. Of course we should try to help | Opinion

The idea that human beings could plant trees that grow more than 300 feet tall and live for 3,000 years sounds far fetched.

Nature does that sorta stuff, not us.

Unfortunately, things have reached a point where we have to try, at least in a handful of severely damaged giant sequoia groves while employing the smartest and simplest methods. Even if doing so requires a little trammeling in wilderness areas.

Humans, through climate change and fire suppression, are largely to blame for the severity of recent wildfires that wiped out nearly 20% of the world’s mature giant sequoias. Thousands of majestic trees, which only grow inside a 60-mile band of mixed-conifer forest on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, are gone, and that sad fact can’t be changed.

As stewards of these places, can we, or should we, repair some of the damage we caused so that the forest has a better chance to regenerate? That’s both a practical and philosophical question. The answer I keep settling on is that doing something beats doing nothing.

Opinion

Which is why the National Park Service brass should look beyond the complaints of a few environmental groups and allow resource managers at Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks to plant giant sequoia and other mixed conifer seedlings in up to six sequoia groves.

A decision by regional director Billy Shott, who oversees more than 65 national parks, including those in California and seven other states, is expected in October. Park officials hope to begin the $4.4 million program this fall, subject to the looming federal government shutdown.

“The goal is to re-establish enough sequoias in the first few years after fire so that we have trees 60, 100, 400 years from now,” said Christy Brigham, the parks’ chief scientist. “Without intervention we will have unprecedented loss of sequoia forest.”

Giant sequoia and mixed conifer planting is already taking place in severely burned sequoia groves located in the Giant Sequoia National Monument on federal land managed by the Forest Service. Those efforts began last spring, and so far more than 286,000 trees (including 14,000 sequoia seedlings) have been planted across 1,380 acres.

Planting has also be done at privately owned Alder Creek Grove, purchased in 2020 by the Save the Redwoods League.

Park service proposal criticized

Sequoia and Kings Canyon carry a higher profile, and thus draw more scrutiny, in that they are home to roughly half of California’s giant sequoia groves (37 total, 27 of which recently burned) and the world-famous General Sherman and General Grant trees.

If park officials wanted to plant giant sequoia seedlings in Giant Forest or Grant Grove, few would notice and even fewer would care. That’s front country. By paving roads through those areas, we’ve already desecrated nature.

By contrast, the current proposal has drawn harsh criticism from environmental groups. Thousands of public comments were submitted in opposition, most of them form letters, before public comment closed in August.

Why such an outcry? Because the six sequoia groves where planting is proposed are located in federally designated wilderness areas where the land is intended to be left in its natural state.

I understand that argument. Of course, when the natural state has been muddied by climate change and the impacts of our own overzealous fire suppression policies, which resulted in hotter and more destructive wildfires than anything previously measured, such cut-and-dry definitions are no longer as simple.

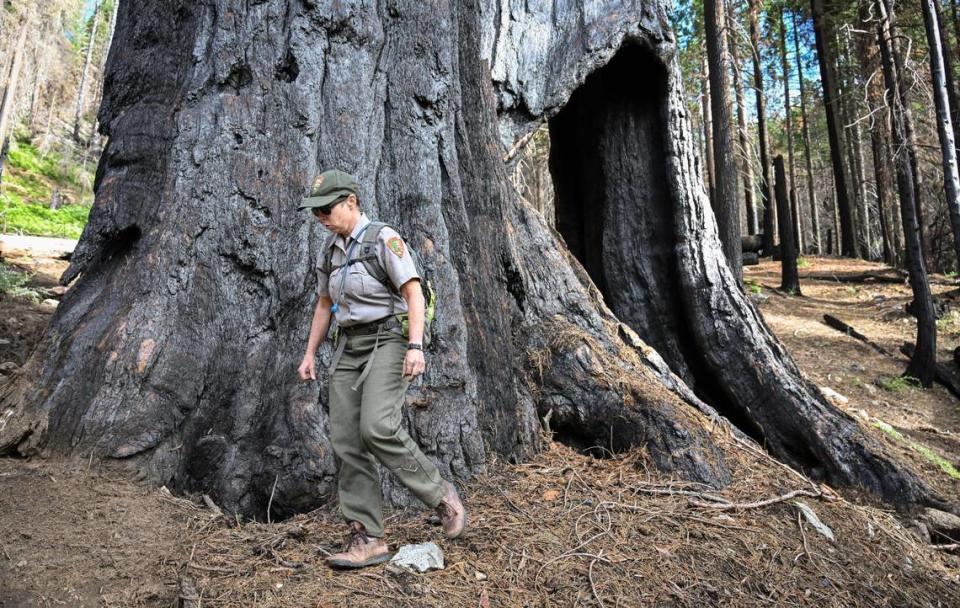

“Those two things together mean we’ve already affected this wilderness area,” Brigham said during a recent hiking tour of Redwood Mountain Grove, where 15% of the grove’s 2,670 acres burned at high-intensity in 2021 during the KNP Complex Fire.

“It’s no longer nature doing its own thing without people interfering.”

Humans already interfered

Humans already interfered with the natural order, and as a result nearly one-fifth of the world’s mature giant sequoias (those with trunks 4 feet in diameter and wider) are gone. The debate now is whether a little more interference could help set things right.

What park officials propose to do isn’t so outlandish. Starting in severely burned sections of Redwood Mountain Grove and Board Camp Grove, deforested areas where no natural sequoia reproduction is occurring, they want to place the 6- to 8-inch-tall seedlings (taken from cones gathered in each grove and growing in private nurseries) in small holes dug by shovels. No watering or weeding would occur.

Yes, it will take helicopters and mules to deliver all the baby trees and other equipment, and that makes some people frown. But choppers and mules are employed in back-country areas all the time.

Even in nature, the chances of a seedling giant sequoia becoming a monarch tree are extremely low. Roughly 22% survive their first winter, according to studies cited in a Park Service fact sheet, and only a quarter of those make it through the second. If a certain acre of forest contains 62,055 first-year seedlings, just 2.61 trees make it to 3,000 years old.

Those are long odds, and again I’m skeptical that human beings can replicate them. Park officials may end up planting tens of thousands of sequoia seedlings, monitor their status over the next 10, 20 and 50 years and see none reach maturity.

The whole thing could end up being a waste of time and effort. But at least we’ll have tried to repair our own damage.