Yahoo 9/11 10th Anniversary

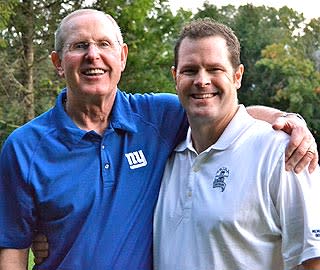

Yahoo 9/11 10th AnniversaryGiants' Coughlin coaches son through 9/11

Tim Coughlin remembers every chilling detail — the smoke, the screams, the surreal and sickening sight of airborne bodies landing on the pavement. And a decade after escaping from the second of the World Trade Center towers to be struck by a hijacked airplane, Coughlin can still recall the worry in his father's voice, and the comfort it provided as he fled the cataclysmic scene.

Most football fans probably wouldn't describe Tom Coughlin, the New York Giants' exacting, hyper-intense head coach, as a calming force. Yet as Tim, then a 29-year-old bond trader for Morgan Stanley, fought through the horrifying fallout from the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history, sharing the moment via cell phone with his dad brought a measure of order to the chaos.

As Tim says now, "I know my father. I know the inflection in his voice. I know when he's dead serious, which is 92 percent of the time. His message was, 'Do what you have to do to get away from that building as soon as possible.' It was really helpful to have my dad on the phone. To be able to talk with him, as it was all happening, it was the greatest sense of calm."

Tim had just reached the ground floor and confronted the wreckage of Ground Zero as he took the call from his father, who at the time was head coach of the Jacksonville Jaguars. For Tom, that connection came after a gut-wrenching, 45-minute stretch of not knowing whether the second eldest of his four children was safe following the initial explosion.

In that sense, Tim's successful descent from the 60th floor of Two World Trade will always make Sept. 11, 2001, a day that triggers emotions of gratitude and relief for the Coughlins.

"For Tim to be able to survive that," Tom says, "I just feel like the Holy Spirit took him by the hand in the second tower and guided him out of there."

Yet Tom Coughlin, a man who has spent the past decade working diligently to support soldiers, police officers, firefighters and others associated with the response to the tragedy, won't be in a celebratory mood on the 10th anniversary of 9/11, which he'll spend on the visiting sidelines of FedEx Field as the Giants open the 2011 regular season against the Washington Redskins.

"It'll be a very emotional day," Coughlin says. "It's incredible that it has been that long, to be honest with you. And the whole idea with me is, America cannot forget what we went through as a nation at that time — and we cannot forget the Americans we lost, and their families who lost them, and the brave people who acted heroically in the aftermath. My reverence is based on that."

The degree to which Tim Coughlin reveres his father was clear to me two years before the tragedy, when I went to Jacksonville to write a story on the man who the following January would take the Jags to their second AFC championship game in the franchise's first five seasons. I interviewed Coughlin's wife, Judy, and each of their four kids, and Tim managed to crack me up when discussing his father's quirks (such as planning vacations down to the minute) and choke me up when speaking about the man's character.

When I learned shortly after the attacks that Tim had fled from one of the towers, I interviewed him again, and the entire conversation was gut-wrenching. Hearing him talk about his experience was haunting, and when I sat down to write about it, I remember being fixated with his father's fear:

For a treacherous 45 minutes last Tuesday morning, Tom Coughlin, a man who traces his professional success to an ability to predict behavior and control his surroundings, was as helpless as so many tens of thousands of Americans with loved ones in the line of fire. The coach was holed up with his assistants in a staff meeting room at the Jaguars' facility, working on the game plan for the following Sunday's scheduled meeting with the Chicago Bears, when his daughter, Keli, called and informed him that the north tower had been struck by a commercial aircraft. He turned on the TV and told his secretary to dial Tim's cell phone repeatedly, spending his time pacing between his office and the nearby meeting room.

As it turned out, Tom and Judy had coached their son well to prepare for such a moment. He demonstrated composure, compassion and courage during the disaster, even as he confronted the possibility that some of his friends who worked at One World Trade had been directly in the first airplane's path.

When that explosion occurred, Tim, who had just finished making trades by telephone, looked out the window of his 60th floor office at Two World Trade and saw the adjacent north tower engulfed in flames. "I thought it was a bomb," Tim told me afterward. "The whole floor froze for about 30 seconds. The scariest part was that people near me were saying they could see people jumping out the windows."

Everyone made a beeline for the stairwell. When Tim reached the 44th floor, a security guard stopped the group and told them, "It's OK. The building is secure." Some of Tim's co-workers took the elevator back up to the 60th floor, but he was skeptical. He and several other colleagues instead moved into the jam-packed 44th floor lobby and waited.

Says Tim now: "My gut was, 'I'm leaving this building.' I wasn't alone in that. There was no way I was going back up to my floor. My boss went back up to the 60th floor, as did some others. They were all lucky enough to get out, but if I'd gone up it would have been real close."

Then, five minutes later … BOOM. The second hijacked jetliner hit the south tower, roughly 23 floors above. "The whole building shook," Tim said afterward. "People thought they were going to die. After that, it was like a stampede."

As much as he wanted to flee, Tim's conscience wouldn't allow it. He saw panicked workers, mostly women, getting pushed aside and knocked over in the rush to the stairwell. Tim and several others held their ground, pushed back the mob and helped prop up those who had stumbled. Only after the floor had cleared, he said, did they enter the crowded stairwell.

The descent, conversely, was surprisingly devoid of panic. Looking back, Tim, now a bond trader for J.P. Morgan, believes the poised behavior of others on the stairwell may have saved his life.

"Because there were some people who'd been through the first [World Trade Center] bombing in '93," he says, "there was a sense of orderliness and calm in the way people went down the stairs. That's the reason why I'm here, I believe."

Another calming force, for Tim, arrived via the magic of cellular technology. Though his phone couldn't dial out — text-messaging wasn't an option back then — Tim's brother, Brian, who was attending law school at the University of Florida, was able to get through after repeated attempts. At that point Tim was on the 30th floor; they stayed on the phone for most of the walk down, and shortly after he hung up he fielded his father's call, just as he was about to exit the building.

"You need to get out of there RIGHT NOW," Tom told him.

"Dad, this is like Beirut, man," Tim said, pausing to survey the smoking wreckage outside the lobby doors. "It's just terrible, awful out here."

"Don't waste any time," Tom implored. "Just drop everything and GO."

Tim and numerous others took an underground subway passage that fed out on Broadway. He was a mile north when, 20 minutes later, Two World Trade collapsed.

It was an unforgettably terrifying experience, and Tim couldn't completely move on if he tried — he works in midtown Manhattan and, he says, "I still see a lot of the same faces I saw 10 years ago. It makes it that much more relevant to me. I still drive in every day [from New Jersey]. I still look downtown and see the emptiness."

Many of Tim's friends died in the attack, including one with whom he was extremely close: Chris Lunder, a bond broker for Cantor-Fitzgerald who worked on a floor near the top of the 110-story One World Trade. He also mourns the passing — and marvels at the courage — of the rescue workers who blew by him on the staircase, headed in the opposite direction.

Says Tom: "I have tremendous admiration and respect for the firefighters who walked past him and went right up there into a building that was 2,000 degrees. When you think about the bravery it required to do something like that, it's just incredible."

Now a father of three young children, Tim couldn't be prouder of the way his dad has lent his support to those who serve. Two years ago, Coughlin joined four other current and former NFL coaches on a league-sponsored tour of the Persian Gulf that has since become an annual event to boost troop morale.

During the Giants' magical 2007 season, Coughlin introduced his players to Lt. Col Greg Gadson, an army officer who lost both his legs while serving in Iraq. Players cited Gadson as an inspirational figure in the team's unlikely drive to a Super Bowl XLII victory over the New England Patriots, an achievement Tim Coughlin calls "the greatest day of my life."

Ten years ago, having survived a catastrophe, Tim's regard for his father was palpable. "I understand my dad probably more than 99.9 percent of the population," he said then. "I know how he is. He's an extremely caring person, and obviously he loves me very much. Even though he's on a phone in Florida, he wants to take charge and help me get out of there."

If anything, the son's estimation of his father has grown in the ensuing decade.

"I don't need to tell you that in the business of football, people get torn down every day," Tim says. "It's just a matter of the business he's in. Well, let me tell you: My father is one of the greatest people I know.

"As I get older, it's easy to see the person that he is. What he does away from football, he doesn't need media coverage or for it to be broadcast, but he truly cares about people. He genuinely is one of the best people I know. He goes out of his way to give back to the community.

"He makes sure the police officers and the firefighters know how much they mean to him, how much he appreciates our service people. The people who gave their lives to 9/11, whether they knew it or not, were being heroic — and they were doing their jobs. He never wants their sacrifices to be forgotten."

The night before the 10-year anniversary of 9/11, Tom Coughlin plans to speak to his players about the tragedy and its impact upon the nation. He likely won't share his personal story, but if the idiosyncratic, obsessive coach seems overcome by emotion, it won't be a mystery as to why.

"We know this is just one story," Tom says of Tim's experience. "We're on our hands and knees thanking God for this miracle. And right now my whole spirit and emotions are in recognition of the families of those that paid the ultimate price. It did change our lives and create a whole different focus for us as a nation. So yes, it's a time of reflection.

"And my whole feeling is, let's never, ever, ever forget this."