‘Gigantic’ bones stumped experts for centuries. Now, prehistoric mystery is solved

In 1850, Samuel Stutchbury dropped a bomb on the paleontology world.

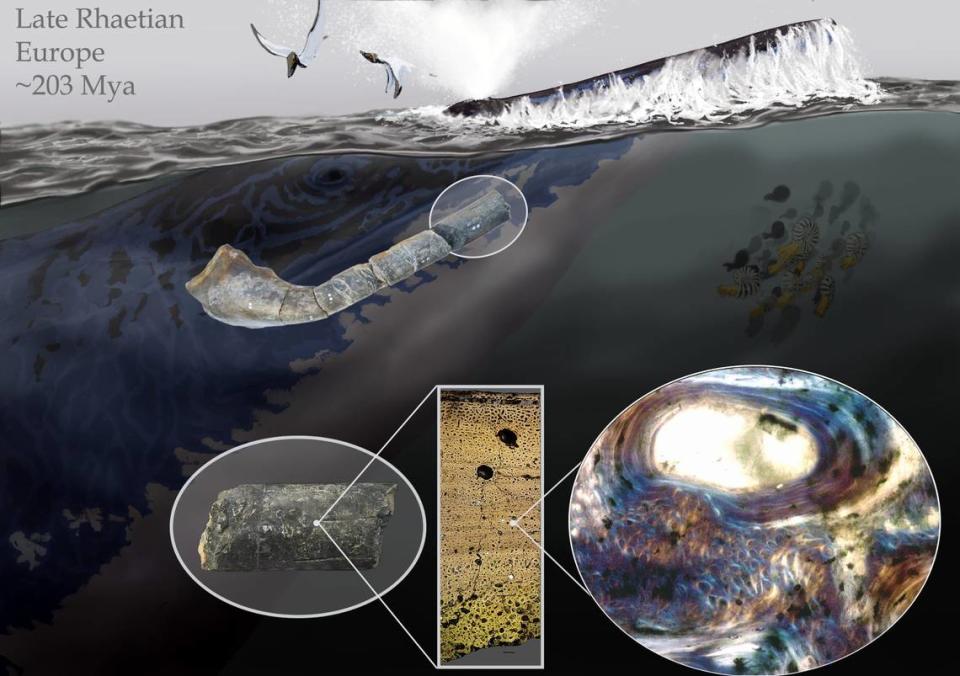

While searching a fossil deposit along a cliff in Bristol, England, he had found a large, cylindrical bone fragment, then published the findings in a scientific journal.

It was unclear what the bones belonged to — other than the obvious fact that they were fossilized, confirming a prehistoric origin — and the debate on their possible species continued as a puzzle for paleontologists to try to solve for 150 years.

“Several similar large, fossilized bone fragments have been discovered in various regions across Western and Central Europe since the 19th century,” researchers from the University of Bonn in Germany said in an April 9 news release. “The animal group to which they belonged is still the subject of much debate to this day.”

That was, until, a graduate student picked up the bones.

While studying for a master of sciences in organismic evolutionary ecology and paleobiology, Marcello Perillo began examining the bone structure of the mysterious samples.

“This work started as my (master’s) thesis project and being able to have concrete positive results in paleontology is never given or assumed, moreover for a student with small experience in the academic environment,” Perillo told McClatchy News in an email.

Stutchbury, at the time of his study publication, thought the bones might belong to an extinct crocodile-like land creature, according to the release, while other researchers throughout history proposed a long-necked dinosaur origin, like a sauropod, or a stegosaurus or even a species not yet discovered.

One thing was for sure — the animal was big. But, it was a tiny piece that finally solved the puzzle.

“Bones of similar species generally have a similar structure,” Perillo said in the release. “Osteohistology – the analysis of bone tissue – can thus be used to draw conclusions about the animal group from which the find originates.”

Perillo gathered samples from the various bone pieces that had yet to be classified and looked at them under a microscope, according to a study of his work, along with his research team, published April 9 in the journal PeerJ.

He wanted to take a closer look at the microstructure, the tiny connections inside bone that give it shape and strength.

“I compared specimens from South West England, France and Bonenburg. They all displayed a very specific combination of properties,” he said in the release. “This discovery indicated that they might come from the same animal group.”

The bones had an “unusual structure,” the researchers said, with long strands of the protein fiber collagen interwoven in a very unique way.

When Perillo compared the structure to fossils of similar size from known species, he found a match.

The bones belonged to the jawbone of a gigantic ichthyosaur, an aquatic reptile roughly the size of a modern-day blue whale.

“When we found proof that the samples we collected all presented the same features, it was a really good moment!” Perillo told McClatchy News. “The research group was quite enthusiastic about what we found out. Moreover, the bone structure we described quickly became a matter of discussion in our group. Many of us in Bonn are working with paleohistology and realized that we may be looking at an undescribed, novel tissue. (It) gave all of us a lot to think about.”

The Giant Triassic ichthyosaurs quickly rose as an apex predator of the seas approximately 252 million years ago, Perillo said, and like other aquatic mammals today, they kept up a healthy diet to maintain their massive size.

While much about their ecology is speculative, paleontologists believe they may have used bulk feeding, like some modern whales, or a hunting strategy like killer whales and great white sharks, Perillo said.

Most of the bones discovered have been much smaller fragments, Perillo said, but their remains disappear completely from the fossil record at the end of the Triassic period, about 201 million years ago.

“The fossils we studied come from sediment deposited in the shallow epicontinental basin that covered most of Europe, so we can think of something similar to a Mediterranean Sea, perhaps with slightly warmer waters,” Perillo said. “We know for sure that they were ocean dwellers and a study even suggested there is evidence to support that some giant ichthyosaurs may have undergone migrations to possible nurseries or reproduction areas, which is overall logical to think about.”

Perillo said while the species may have been identified, there are still more questions to answer.

“The dietary questions are still open and there is a lot of research that needs to be done,” he said. “The microstructure of the bone is extremely peculiar and deserves further research to see if there are modern day analogs.”

The University of Bonn is in Western Germany, about a 20-mile drive south from Cologne.

Carvings discovered on rock walls in Brazil — then something prehistoric is revealed

Winged ‘fairy’ creature preserved inside amber belongs to ‘enigmatic’ new species

Teeth in walls of Kentucky cave belong to sharks that lurked 325 million years ago

‘Chicken from Hell’ — an ‘unusual’ ancient species — once roamed the Midwest, study says