The Girardis, the Secret Service and wire fraud claims that nearly ruined a Hollywood designer

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the fall of 2016, two influential men in Los Angeles faced money troubles.

The head of the L.A. office of the U.S. Secret Service, Lorenzo Robert Savage III, thought he was being shortchanged in a lawsuit over a defective braking system in his family’s Volkswagen minivan.

And Tom Girardi, then at the height of his power, was borrowing heavily to fund his law firm and increasingly upset about the size of his wife’s American Express bill.

To address their respective problems, Savage and Girardi and their spouses turned to each other.

Girardi agreed to represent Savage and his wife for free in a bid to extract a larger cash settlement in the minivan case. When his efforts failed, Girardi dug into his own pocket to pay the family at least $7,500.

The same month, Savage arranged for Secret Service agents from a financial crimes squad to meet with Erika Girardi about what she said were excessive charges to her credit card by a Hollywood costume firm.

Agents under Savage aggressively pursued the case, ending in a federal wire fraud indictment of the company’s co-owner in 2017 and, for Tom Girardi, an American Express refund of about $787,000 at a time when he was swimming in debt.

But prosecutors quietly dropped the case a year and a half ago, after Girardi’s law firm collapsed, and questions are only emerging now about the origin of the case and whether there was enough evidence to support criminal charges in the first place.

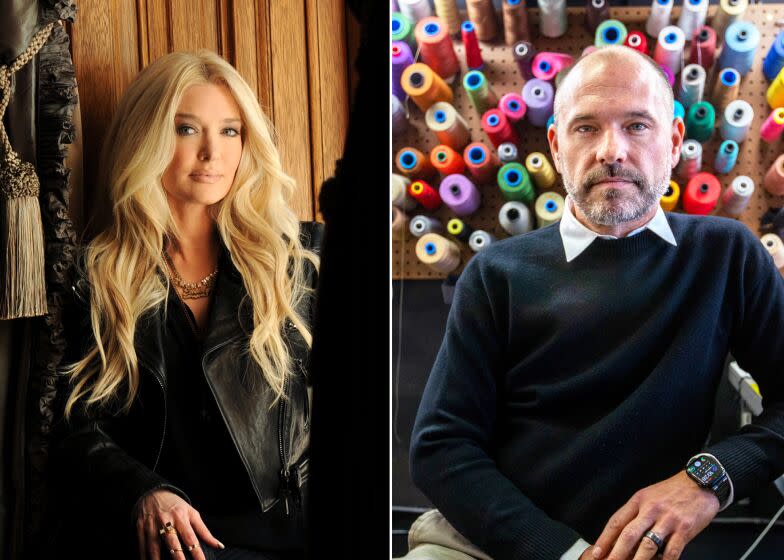

The connections between Girardi and the Secret Service's L.A. chief were recently uncovered by The Times. Their relationship was not disclosed to the costume firm co-owner, Christopher Psaila, who was facing the prospect of years in prison, or his defense counsel. Nor were they informed of the payment Girardi made to the Savages during the investigation, they told The Times.

Psaila told The Times that after his arrest, he scrutinized every charge his costume company, Marco Marco, made on Erika Girardi's credit card and determined they were all legitimate. He said the unfounded accusations nearly destroyed his business and devastated him personally. The costs, he said, included being turned away when he and his husband attempted to adopt children.

“I lost complete trust in the justice system,” Psaila said. He pointed to the sway that Tom Girardi held in the legal and political worlds and the important people he counted as friends. “That was what I was up against, and that is terrifying.”

Erika Girardi said in an interview that she remained certain that Psaila falsely billed her for hundreds of thousands of dollars and cited a conversation surreptitiously recorded by the Secret Service in which he acknowledged some overbilling.

“In no way did I pull a scam to get $760,000 to help anybody get this money,” she said. She said she feared that the public would believe any bad thing said about her given the disgrace surrounding her estranged husband and his law firm.

“The truth needs to be told here. And it’s not some great fabulous story where I pulled a rabbit out of a hat for money.”

Savage, who retired in 2018, denied any exchange of favors, saying the credit card complaint and his minivan case were "completely unrelated." The Secret Service and the U.S. attorney’s office declined to answer detailed questions about the case.

Tom Girardi was indicted last week on federal wire fraud charges, which accuse him of swindling more than $18 million from clients from 2010 to 2020. He is in a court-ordered conservatorship following his diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and unavailable for comment.

***

Secret Service agents in helmets and body armor burst through the doors of Marco Marco’s studio at dawn with guns drawn. Ordering seamstresses outside, about 10 officers rifled through the premises, sending feathers, crystals and bolts of silk, sequins and leather to the ground and scattering hand-drawn sketches of couture designs for ballerinas, circus performers, drag queens and stars like Britney Spears, Mariah Carey, Cardi B, Katy Perry and contestants on "RuPaul's Drag Race."

In addition to protecting the president, the Secret Service has the authority to investigate certain financial crimes, including credit card fraud. Those probes often involve large-scale criminal rings targeting numerous victims, cases that comport with the agency’s stated plan to combat “criminal schemes that pose the greatest risk to U.S. economic prosperity and national security.”

During the January 11, 2017, raid, the agents informed Psaila and his business partner, designer Marco Morante, that they were looking into $800,000 in allegedly fraudulent charges to Erika Girardi’s American Express card.

“We couldn't even fathom that. It just seemed insane to us,” recalled Morante, who then counted the “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star as both a customer and friend.

Psaila, who handled the business side, said he was so confident that the claim was false that he helped agents log into the company’s accounting software, reasoning, “Let’s solve this here and now.”

By the time of the 2017 raid, Erika Girardi had been a client for about three years. She’d been introduced to them by their mutual publicist, who said she was in her early 40s, trying to become a pop star and had a rich husband to foot the bill. Working with Marco Marco, Psaila said, was part of a plan to “go the gay route” in her pursuit of fame.

“We were already a household name in queer households because of our underwear brand and exposure on 'RuPaul’s Drag Race,'” said Psaila, who had started Marco Marco with Morante in 2002 after meeting as students at California Institute of the Arts.

At the time, Erika Girardi wasn’t yet appearing on “Real Housewives” and had, Morante recalled, just 800 followers or so on Instagram. But, he said, her over-the-top sexuality and blonde bombshell looks as “Erika Jayne” gave her a potential appeal to a gay audience — “the ultimate Barbie doll.”

Girardi told The Times she went to Marco Marco because their outfits were cheaper than at Silvia’s, a venerable costumer on Hollywood Boulevard.

“They didn’t help me accelerate my presence in the gay community. That is done through hard work, making records, doing shows,” she insisted.

At her first fitting, Psaila tried to present her with an invoice, but she waved him off, saying the paperwork wasn’t necessary and to keep her credit card on file, he and Morante said.

“It never happens that someone would just dismiss the invoice and not look at it at all. That was bizarre,” Psaila said.

It would be years before the absence of invoices came up again, and by then the Secret Service was getting involved.

The relationship between the business and the performer blossomed between 2014 and 2016. Marco Marco designed outfits for Girardi and her backup dancers to wear in nightclub shows in Denver and Miami, circuit parties in Palm Springs, performances on “Real Housewives,” and music videos for songs such as “How Many F—ks" and “XXpen$ive,” according to the company owners. Her go-to look was a skintight catsuit encrusted with crystals — “always Swarovski,” Psaila said. On one “Real Housewives” episode, Morante was shown squeezing a nearly nude Girardi into a sheer black bodysuit after she jokingly ordered him to “get my fat a— into this thing.”

Soon other celebrities were asking for versions of their own.

“When Paula Abdul came into our studio, she said, ‘I want the Erika Jayne catsuit,’” Psaila said.

The company had bigger accounts, including Spears’ Las Vegas residency and Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, but Girardi’s costumes provided steady work, month after month and year after year, the owners said. At its peak, Psaila said, she accounted for between 20% and 30% of the business.

***

Weekdays, Tom Girardi held court at Morton’s steakhouse in downtown L.A. For decades, he was an almost unstoppable force in California. One of the nation’s most esteemed trial lawyers and an important Democratic donor, he hobnobbed with Supreme Court justices, judges, governors, police chiefs and real estate developers.

Few knew then that his reputation as a champion of the little guy was largely a lie. His firm was pervaded by fraud and he was routinely stealing from clients.

It would be years before those revelations became public. In 2016, politicians, business leaders and law enforcement officials were still happy to be seen with him at Morton’s, where they could count on a free meal and gossip.

One of those was Rob Savage, who had become special agent in charge of the Secret Service’s L.A. field office the previous year.

He struck up a friendship with Girardi at a Chamber of Commerce dinner about a decade ago, but his wife’s family had known the lawyer for decades longer, with two relatives interning at Girardi’s firm in the 1990s. He was a regular at Girardi’s annual Super Bowl parties, where police chiefs, judges and top attorneys — almost all men — downed cocktails while wearing football jerseys over tuxedos.

In response to written questions, Savage said that he “occasionally dined with Mr. Girardi always as a friend and within ethics guidelines” for the agency: “Many times he paid and I treated him a few times, as I customarily do with my friends.”

Savage and his wife, Michelle, had joined a lawsuit against Volkswagen in 2015 concerning braking problems in their used minivan. The couple had signed a written acknowledgment of the settlement that provided for free repairs and a $7,500 payout for plaintiffs like the Savages whose names had been used in the case, according to court filings.

But as the finalization drew near in the fall of 2016, Rob Savage worried that the settlement was too small and had been reached “without holding Volkswagen adequately responsible,” he recalled.

He went to Girardi, who agreed to intervene. Girardi burst into the litigation in November 2016 — in the same period Erika Girardi had started raising concerns about the charges on her American Express card. Her husband began lobbing expletive-laced attacks on the attorneys for the minivan owners, who had spent a year and a half negotiating the settlement, according to a status report in the case and other court records. He accused them of deceit, a particular offense, he said in one filing, given Savage’s stature as “head of the State’s Secret Service” with “massive integrity, clearly.”

Savage bolstered Girardi's accusations with a sworn affidavit in which he wrote that his former lawyers had “totally mislead [sic] the Savage family all during the litigation.” The lawyers countered that the affidavit was rife with falsehoods, but Girardi kept pressing for a better settlement for the Savages and making sure his opponents knew his clout. In one filing ostensibly about scheduling, Girardi managed to inform the judge of an array of career achievements, including serving as a trustee at the Library of Congress, receiving “the Elite Trial Lawyers Award” from the National Law Journal and the erection of a Times Square billboard proclaiming him “Top Attorney of the Year.”

By then, the Secret Service was actively investigating Marco Marco. When Girardi and the Savages arrived for a court hearing in the minivan case on Dec. 13, 2016, things did not go their way. The judge could barely contain his fury at Girardi.

“This whole sequence of events is extremely problematic,” U.S. District Judge Haywood S. Gilliam Jr. said, according to a recording of the hearing. “I have a really uneasy feeling about the way that this has gone down in terms of respecting and following my orders, and I can't tolerate that.”

Girardi seemed taken aback that anyone would question his integrity and announced a solution that left the courtroom stunned: The Savages would dismiss their case against Volkswagen and he, Girardi, would pay the couple more than 10 times the value of their settlement.

“If the court thinks I intentionally did something wrong or tried to do anything inappropriate, that doesn't work with me, so I personally would pay him $100,000,” Girardi said. The judge sought confirmation from him that the offer was real, and Girardi repeated the plan two more times.

The following day, he filed papers dismissing Savage’s claims against Volkswagen. Asked about the hearing, Savage said, “This was a very embarrassing situation to witness and was not what I anticipated from my expectations of his formidable legal reputation as a premier plaintiff’s attorney at that time.”

Savage said he never received the $100,000 payout, but at a Christmas party two to three weeks later, “Tom handed me a check written for $7,500, the exact amount of the Volkswagen Class Action Settlement.”

“My wife and I were happy that we received what we would have received if we had remained in the [lawsuit],” Savage said.

***

A few months before Girardi got involved in the minivan case, he began complaining to his wife about her spending habits.

“Tom comes home and says, ‘Your Amex charges are really out of control,’” she recalled in an interview. Though few knew it, Girardi was in precarious financial straits, borrowing millions of dollars from a slew of high-interest lenders using his future legal fees as collateral.

Erika Girardi, who has said she knew nothing about her husband’s business and thought he was flush, said that she didn’t have access to her credit card statements and asked him to explain what had upset him. He blew her off, but then confronted her the next month, once again offering no details, she said.

She said she called American Express for help installing an app on her phone that allowed her to see every new charge. In Texas for a performance, she saw a $5,000 charge from Marco Marco that she said she had not approved. She called and said Psaila agreed to reverse the charge, but it later happened again, leading her and two employees to begin reviewing years of account statements. She said they found hundreds of thousands of dollars in charges that seemed to far outpace the number of costumes in her closet and decided to go to law enforcement.

She called her husband’s friend, Savage.

Erika Girardi was familiar with the Secret Service’s jurisdiction over financial crimes, including credit card fraud, she said, because around 2009, she and several celebrities — including Anne Hathaway and Jennifer Aniston — had been defrauded by a Beverly Hills aesthetician who placed phony charges on their cards.

Savage invited her to the agency’s office in downtown L.A. He along with a task force supervisor and two agents listened as she laid out her allegations against Marco Marco with help from her creative director and her personal assistant.

One issue was that Girardi didn’t have many of her invoices. Psaila had provided some after she initially complained, but there were others for legitimate work that she didn’t have, making it difficult to establish whether a charge was erroneous.

Savage said he handed the case off to his underlings and never discussed the probe directly with Tom Girardi. On the day after the hearing in the minivan case, Secret Service agents equipped Erika Girardi with a hidden microphone for a meeting that Psaila said he had initiated to discuss the disputed charges.

The conversation lasted about 26 minutes and produced what Girardi saw as incontrovertible evidence that Marco Marco had cheated her. Psaila, however, said the conversation only proved how panicked he was to be accused of wrongdoing by one of the company’s best clients and how difficult it was to reconstruct years of billing records.

After presenting Girardi with more invoices he had tracked down, he acknowledged “excess billing” of “just over $100,000” that he blamed on a bookkeeper who he said, falsely, had been responsible for running the cards, according to a recording reviewed by The Times.

“In terms of getting this money back to you, Marco and I do take full liability and responsibility for it and we will make it happen,” Psaila said, adding that he planned to get a loan to repay the debt.

“I fear this has happened to other people too,” he said.

Girardi told him the actual amount taken from her was $800,000.

“$800,000?” a stunned-sounding Psaila replied, adding, “I don’t know how that would even be possible.”

Girardi said she found the situation “heartbreaking.”

“There’s a million dollars, well, eight hundred, nine hundred thousand, well, whatever, of my husband’s money that is gone,” she told Psaila. “That is very hard for me to take and it is very difficult for me to explain to him and, you know, all he’s doing is being good to me and all you’ve done is taken my money.”

When agents met up with Girardi after the meeting, she recalled, “they asked me to raise my right hand because they wanted to deputize me because I did so well.”

Psaila said he regrets implicating the bookkeeper, who had nothing to do with the charges, and saying that he had found $100,000 in incorrect charges.

“I was so desperate and panicky,” he said. “I did not want to lose her as a customer.”

Morante at first thought it possible that the company accidentally overcharged Girardi’s credit card a small amount. But he said he never believed Psaila, his partner of 20 years and a “rule follower” who refused to jaywalk in college, had stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars.

When he heard the recording, he said, “It infuriated me because I was like, ‘Chris, you just patsied yourself.’ But I also know Chris, and Chris is very, very nonconfrontational.”

The next month, agents raided the premises.

Psaila and Morante sat on the curb outside their studio on Cherokee Avenue. The headquarters of World of Wonder, which produces “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” was across the street, and employees they knew watched from the windows as agents carted away their computers and other potential evidence.

“It was one of the most humiliating moments among many,” Psaila recalled.

Meanwhile, Girardi and her employees were sorting through her costumes with the Secret Service, matching the invoices she had with the outfits in her closet and the charges on her card.

The criminal charges came four months after the raid: a nine-count indictment on aggravated identity theft, wire fraud and use of an unauthorized access device against Psaila alone. He had never before been arrested or charged with a crime and said he cried as an agency supervisor and two agents handcuffed him. The trio seemed unfamiliar with how to book a suspect in the federal detention center in downtown L.A., calling colleagues from the car and then getting lost in the wrong parking structure, he said.

“They didn't really know...where they were going,” Psaila said. The lead agent did not respond to messages seeking comment. His supervisor did not respond to written questions.

Though the indictment described a “scheme” that cost American Express “losses in excess of $700,000,” the wire fraud counts were based on only seven charges from 2015 and 2016 that totaled less than $63,000.

One explanation for the discrepancy was that American Express had already lost $787,177, largely on the word of the Secret Service. After being contacted by agents, the card company had reimbursed Tom Girardi in early 2017 with credits to his account and a check sent to his office. The company sent the money without performing its own independent investigation or questioning Psaila or Morante. It never filed suit against the pair to recoup the money and never cut off Marco Marco from charging its credit cards.

American Express declined to answer detailed questions about the case. A spokesman, Andrew Johnson, said in a statement that the company “followed our regular processes and procedures throughout this investigation as we dealt with law enforcement.”

He added, “We did not play any role in the criminal investigation of Mr. Psaila or his business other than responding to inquiries from law enforcement.”

There was also the question of why Morante, an equal partner in the business, had not been charged or even interviewed by agents. He said he came to believe that Psaila, who worked largely in the background, was an easier target.

“I have a following, and I'm loud,” Morante said. “And I have a lot of very, very famous, loud, not-white friends who would love to grill absolutely anybody.”

Weeks after Psaila got released from custody, he drove to Fresno to tell his parents in person. He said he was so nervous that on the way, he vomited along the highway.

The case decimated their business, the owners said. Investors pulled out, longtime customers distanced themselves and employees quit en masse.

Morante, whose designs continued to be in celebrity demand, said he never thought about abandoning Psaila, whom he considered instrumental in his success.

“I would be working in a bar or something” without their partnership, he said. “I would have rather gone to do all that jail time for Chris than let that woman or any of these people change reality.”

The case was delayed for years, at first for scheduling reasons and later, disruptions from the pandemic. Erika Girardi remained eager to testify.

“Mrs. Girardi told me she had nothing scheduled in March and is still willing to testify to ‘f— Chris,’” a Secret Service agent noted in October 2017.

“She also inquired about why Psaila hadn’t pled guilty in the case. I told Mrs. Girardi that Psaila was facing multiple years of jail time for his actions which may be why he hasn’t pled guilty yet.”

After his father’s death in 2020, Psaila used a life insurance payout to hire a veteran criminal-defense attorney.

Stanley Greenberg, a former federal prosecutor who has practiced in L.A. since the 1970s, said he found it odd that the Secret Service, which frequently partners with other law enforcement agencies on sprawling financial investigations with many victims and millions of dollars in losses, had taken on a “garden variety fraud case.”

A task force supervisor and another agent claimed to have extracted a partial confession from Psaila after the raid, but they hadn’t recorded the conversation or taken notes and he denied making the statements.

“The Secret Service just seemed to have a very intimate role in this whole thing and it included getting money for [Tom Girardi] and not bothering to question one of the main witnesses,” Greenberg said, referring to Morante. “Everything just reeks of the fact that they were doing some kind of favor.”

Psaila had assembled evidence for prosecutors that he said corroborated more than 100 disputed charges, including text messages with Erika Girardi’s employees, social media posts of her outfits, television clips and invoices.

“I realized that there wasn't a discrepancy at all,” Psaila said. “Everything I came across was documented.”

Though almost every criminal case ends in a plea agreement, Greenberg said he told the prosecutor he was taking the case to trial.

“I had reached the point where I said I’m not going to let him plead guilty,” Greenberg said.

He said he informed the prosecutor in late September 2021 that he planned to call both Girardis as witnesses in the trial. By then the Girardi Keese firm had collapsed and Girardi had been exposed for stealing client funds. It was unclear whether the lawyer would or could testify given the conservatorship. Greenberg moved ahead anyway, saying he wanted answers about the Girardis’ financial situation and their contacts with the Secret Service.

Shortly after he started sending subpoena notices, Greenberg said, he received a call from the prosecutor informing him they were dismissing the charges. Why, he asked.

“She said, ‘We just took another look at the case,’” he said.

Erika Girardi learned of the dismissal on Twitter. Savage was no longer at the agency, but she placed an irate call to the main case agent.

“I said, ‘How could you do this to me? I am at a terrible point in my life. … This makes me look like a liar,’” she recalled. She said he apologized and mentioned his relative inexperience at the time of the investigation.

A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office in L.A. issued a brief statement implying lapses on the part of the Secret Service.

“We ultimately determined that law enforcement evidence preservation issues undermined our ability to prosecute the case and the interests of justice supported dismissal,” the statement said.

Greenberg, the defense attorney, scoffed at the explanation. He said that the prosecutor never informed him of any missing evidence.

“It’s an absence of evidence, because they did a sloppy job in the first place,” Greenberg said.

Psaila said he still struggles with the emotional impact: “I’m totally a shell of a human now.”

He and Morante have slowly rebuilt the company, with Marco Marco receiving an Emmy last year for costume design in the HBO reality series “We're Here.”

“We really were forced to start from scratch,” Morante said.

Erika Girardi is gearing up for a new season of “Real Housewives” while fighting off numerous lawsuits stemming from the misuse of money at her husband’s firm.

She said she was appalled that Marco Marco’s owners were suggesting she had betrayed them.

“Now that my reputation is in the toilet and Tom's in a home … of course, [they are saying] she did this," she said. “There was no reason for me to do this."

Tom Girardi no longer picks up the Morton's bill for Savage or other officials. Asked whether he had any regrets about his dealings with the disgraced lawyer, Savage told The Times that it was up to others “to hold him accountable for any wrongdoing he may or may not have committed.”

“While we were friends I was unaware of any allegations of misconduct, as were many other local, state and federal officials,” he said.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.