As a girl, my mom taught me that being fat was the worst thing a woman could be

When I was 13, my mother told me, “I love you Rebecca, but I don’t like you.” That night, I wrote “I hate my mother” in big angry letters followed by page-sized exclamation points in the diary I kept under my bed. We’d been fighting for months, mostly about my body, my weight, my very being. About her need for me to be something she envisioned as the perfect daughter and my anger at her for not loving me unconditionally. I held on to that anger for a long time. It softened over the years, but it still lived with me.

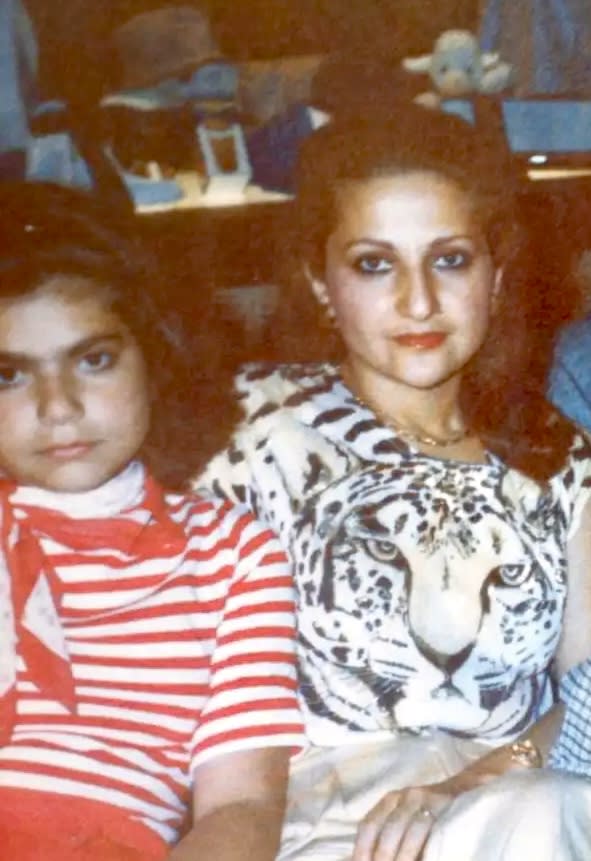

Ever since I can remember, my mother has been on a diet. She grew up in a time where every message she got told her that a woman’s worth was measured by her beauty and her body. Discussions of women’s bodies, including mine, have been an integral part of my life since I was old enough to understand what it meant to be female. To my mother, the worst thing a woman could be was fat.

Unfortunately, I ended up being that worst thing.

Once I hit puberty, I started gaining weight. My mother was devastated. She did everything in her power to try to get me to lose weight, including putting me on diets, instituting weigh-in sessions and trying every incentive, both carrot and stick.

One day when I was in middle school, she found me in our basement eating cookies. Instead of yelling at me, as she’d done many times before, she put her arms around me.

“Rebecca, I’m doing all this because I love you. You’re beautiful, you just need to lose weight. You’re a smart girl, you can do it. Just control yourself.”

“I can’t,” I said through heaving sobs.

“You can. I promise. It just takes will power. Trust me, I’ve been doing this my whole life. It’s hard but it’s important. You have to do it.” She tightened her embrace with the last words for emphasis.

I vowed to try harder.

My mother’s steadfast position on the importance of being thin created a coldness between us and a deep need for me to fight back — against her rules, against her conditional love, against what I thought she was telling me: I won’t love you if you’re fat.

One Saturday afternoon that same year, our kitchen caught fire. My mother had left a pan of oil on the stove and forgotten about it. When the fire alarm went off, she ran into the kitchen and without thinking grabbed the pan with her right hand. The scorching oil poured over her skin, instantly melting it off. I could see her screaming from the backyard. In shock, I stood frozen in the backyard. I didn’t run into the kitchen to help. I didn’t cry.

The next few weeks, the dressing on her hand had to be changed every couple of hours because of the continuous draining of pus. I watched her from a distance, not helping with the bandages or showing emotion. I was too broken to comfort her. She saw me withholding my love, felt my resistance to care about her suffering. The distance between us grew.

I never achieved the thin body she wished for. Throughout the next decades, I learned to accept my body the way it was. I got married, had children and built a legal career at a nonprofit that gave me meaning and purpose. All along the way, even though our relationship continued to be strained, I still went to her, seeking love. I needed her. I needed my mom.

Decades later, on our daily call, I asked her if she remembered when we went to lunch before my driving test, and I ordered a Caesar salad with no dressing or croutons.

“The waiter came back with just a plate of lettuce!” I laughed. It was one of my favorite stories: absurd, funny, tragic.

“Of course, I remember, it was ridiculous,” she said, also amused.

“I was terrified of you,” I said in a lighthearted way that we both understood. Or so I thought.

I waited for her to say something funny in response. But there was silence. I thought maybe the line disconnected.

“Are you still there?” I said.

“You know,” she said, at last, “I was 22 when I had you. I’d gone from my parents’ house to my husband’s house. I didn’t understand much about life. I was doing what I thought was right. But I know now what I did to you was wrong. I’m so sorry I hurt you.” She paused.

I was speechless, surprised by her apology.

She went on, her voice shaking, “Seeing you all these years living your life the way you have has taught me what really matters. What it means to be a woman. I’m so grateful for that.”

I told her I knew she was doing the best she could. “And I wasn’t easy,” I reminded her. “I tormented you. Lashing out. I thought you didn’t love me.”

“You were a difficult child!” We laughed, both tearful now.

That conversation opened up an opportunity for us to begin sharing our regrets and our pain, which we have done ever since.

My mother and I talk every day on FaceTime, and even though I don’t talk about my weight, I listen to her talk about hers. It’s still really important to her.

“I know it’s silly and it doesn’t matter,” she says. “But it makes me so happy when I lose those two pounds!” She laughs.

Recently, when talking to my mom, I accidentally revealed my angst about my pandemic weight gain. Instantly, all the fear and pain of that 13-year-old girl came flooding back. “I shouldn’t have brought up my weight. Please don’t say anything about it.” I pleaded.

She looked at me through the iPhone screen with so much love and a bit of sorrow.

“Rebecca, I love you. You’re the best thing in my life. I haven’t cared about your weight in decades. I’m so proud of the woman you’ve become.”

I felt my body relax.

After decades of talking about this issue, I knew she still cared, and if I was being honest, so did I. But I also knew she could care and love me completely. Just as I could struggle with accepting my body’s imperfections, while also feeling fulfilled and happy with who I was.

My mother continues to diet constantly but instead of carrying shame about my body and hers, like she had for decades, she feels tenderness and love, and regret for the distance her shame put between us all those years.

As for me, I still struggle sometimes with receiving her unconditional love, believing it, but I’m enormously grateful and proud of the relationship we’ve developed. Our complicated mother-daughter journey has not been an easy or smooth one, but we’ve come through it loving and accepting each other more than either of us expected.

Do you have a personal essay to share with TODAY? Please send your ideas to TODAYEssays@nbcuni.com.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com