As a kid, I was on the cover of my mom's book. Now I'm unpacking all the trauma it caused

I am on the cover of a book. My mom’s book, “Stop Struggling with Your Teen: A Complete Easy-to-Use-Guide for Parents of Pre-Teens and Teens.” It was self-published in the ’80s, eventually picked up by a major publisher and sold over a quarter million copies. But I wasn’t a troubled teen. I was only 9 years old.

A photo of me, taken at summer camp, randomly sat out on the kitchen counter for over a week. My mom, a family therapist, hadn’t had the time to put it away yet. She had invited Diane, a talented cover designer, over to our house and offered her something to drink. Diane noticed the photograph of me: a kid with curly red hair, ambushed by freckles, wearing a mismatched top and shorts, leaning against a cement wall and staring off into the distance. Diane turned to my mom. “This is the exact look you want for the cover.”

My mom was confused. Had Diane thought she left the picture out on purpose? It was just an image of her youngest child looking bored at camp. She tried to clarify, “That’s Rachel, my daughter.”

Diane didn’t miss a beat. “She’s perfect.”

Had Diane seen what my mom hadn’t? But Diane couldn’t have known my secret: I was sexually assaulted when I was 5 years old by a 16-year-old boy in the woods across from our house. No one, not even my mother, would know my secret until 38 years later, when the memory I had blocked resurfaced.

The picture from summer camp was taken four years after my childhood assault.

Even though Diane didn’t know my secret, maybe as an artist, she was trained to see what wasn’t obvious to others. In that photo, I wasn’t bored; I was despondent. My mom, an exceptionally skilled therapist, was also trained to see things. And yet, she had completely missed the signs that I was assaulted. I started to spend large swaths of time alone playing make-believe (she thought I was creative); I refused to wear dresses (to be more like my older brothers, she assumed); and I once violently kicked and nicked my dresser drawers (a normal childhood outburst; her clients’ children did much worse).

Even though Diane and my mother may have seen different things when they looked at my photo, they agreed: The look of unhappiness on my face would resonate with struggling parents of distressed teens.

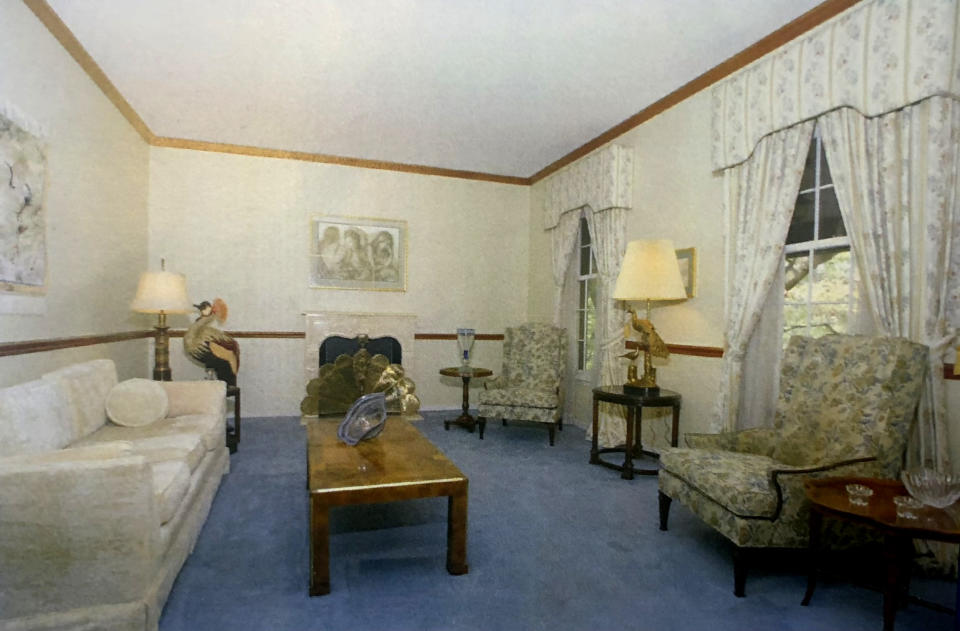

After Diane left, my mom asked to talk to me in the living room. Unlike the rest of the house, the living room was austere, cold. It was filled with a white couch and other expensive furniture and artwork, not a very conducive environment for three active kids. But it wasn’t meant for us. It was used as the waiting area for my mom’s clients, who she saw in her office at the back of our house.

Sitting in the living room with my mom, I knew she had a serious question. Only serious conversations were saved for this room. She asked me how I would feel if my picture was used for the cover.

“The answer is completely up to you, Rachel, but the one stipulation is, you can’t change your mind afterward.”

I can’t imagine she really used the word stipulation: It was much too big for my vocabulary, but this is how she retells it. I had a history of being indecisive and moody at times, and would often backtrack on decisions I made, so she takes pride in this part: She was teaching me the importance of consequences. My mom made it perfectly clear: Once I decided, there was no turning back. What I remember most is not the emphasis she put on the permanence of my choice, but rather, the look of anticipation on her face. She was hoping I’d say yes. I was ambivalent. I craved her attention and didn’t want to disappoint her, but I was conflicted at the thought of extra attention and extra eyes on me. I didn’t understand that the discomfort I felt stemmed from my sexual assault. I wish I had understood more. I wish she considered the importance of protecting my privacy. Why hadn’t she considered a lot of things?

Sitting in the living room, the living room where clients would wait for my mother, I looked at her and answered, “Yes. You can use my picture.” I paused, then added, “But I don’t want my friends to know.” My answer makes me sad. It shows what little concept I had of what it meant to be on the cover of a book, how small my 9-year-old scope of understanding was.

When the doorbell rang back then, I was often in charge of welcoming clients. My mom was finishing up a session, or clients arrived early when she was still upstairs putting on her makeup. My brothers were too lazy and too smart and stuck me with the awkward job. I never realized until I was an adult how inappropriate it was to have me answer the door. My greeting clients violated their confidentiality, but worse, it exposed me to people in real emotional pain. I may not have known specific reasons clients came to see my mom, but I felt the heaviness they carried.

I opened the door to tired parents, bitter couples, single moms, single dads, people who were lost and hoping to be found. I let them in and showed them to our living room.

Some made small talk. “You’ve got a lot of freckles.”

Some had gotten to know me. “What grade are you in now? Third?”

Others didn’t talk at all, but only nodded and went to their spot on the couch to patiently wait for my mother.

My mom decided to write a parenting book because she felt an hour wasn’t long enough. Before becoming an Adlerian-trained therapist, she had been a fourth grade homeroom teacher. A good one, too. She considered herself an educator and wanted to teach and help parents outside of the time she spent with them in sessions. Plus, she sought the limelight: “I have my Donahue dress ready,” she’d say.

When “Stop Struggling” was featured in Family Circle magazine, a popular, nationally syndicated publication, sales exploded, and hundreds of book orders started to come in daily. Her book was featured at my elementary school book fair. I was unaware of it until a friend came running down the hallway, eyes wide: “Rachel, you won’t believe it. There’s a girl that looks just like you, and she’s on the cover of a book!” I couldn’t deny the similarity and shyly confessed it was indeed me. If I could have melted into a puddle and disappeared, I would have. But instead of telling my mom how mortified I was, I repeated the details of the day as if I were sharing a humorous anecdote. “Can you believe what happened to me at school today?” My mom delighted in the story, which made me happy. I swallowed my embarrassment and shame.

My mom made a poster-sized version of the book cover. Her reasoning was a bit ingenious; she was being featured as a parenting expert on TODAY, but the producers wouldn’t promise to mention her book on air. The interview was filmed in her home office, and the life-size photo of me hung perfectly framed, not so inconspicuously, in the background. The picture stayed in her office long after the interview. It always felt surreal to know my photo was in the background during my mom’s sessions. What did clients think about me? What did they think about our relationship? Did they think she struggled with me? That I was a difficult child? I sometimes wished the girl in the picture was real. I could have been a fly on the wall, sharing in some of that precious time with my mom.

My mom’s book continued to meet with success, and while originally self-published, “Stop Struggling with Your Teen” found itself in the middle of a bidding war between two major publishing houses. Penguin Books, the victor, decided to keep my picture for the next edition, but then soon realized I was wearing ’80s iconic Esprit brand clothing, and they didn’t have copyright. My picture was replaced immediately, and a new faceless cover was born.

Most people who know me have no idea my photograph was ever on the cover of my mom’s book. I have come to realize that being on the cover did have a profound effect on me. Having been sexually assaulted, I was so vulnerable, and any extra attention made me uncomfortable. Being in the spotlight was overwhelmingly scary, and the fear of all those unwanted eyes looking at my picture on the cover drove me deeper into my well of silence. I didn’t know how to voice my feelings to my mother. I internalized my pain and protected her from my thoughts, more than she seemed to have ever protected me.

When I first started psychotherapy as an adult, after the memory of my childhood assault resurfaced, I truly believed my mom and I had a wonderful relationship. We spoke daily. I would ask for advice on parenting, and sometimes we shared writing woes. I had grown up to be a writer too; a different kind of writer, a screenwriter, but we both knew the agony of first drafts and self-doubt. Still, every phone call, I held back. I never shared how deeply depressed or lonely I was in my life, how disconnected I was to her.

When the memory of the woods came back to me, I told my mom. But I was rote in my retelling. I feigned unaffectedness. I shrugged: “It couldn’t have lasted more than five or ten minutes. It was no big deal.” Later my mom would show deep remorse. She would google my childhood assaulter. She would fantasize about going to his house and confronting him. She would spend hours and days wondering how she could have missed the signs, and she would apologize to me.

In the moment, though, despite showing surprise and acknowledging she never knew, she mirrored my nonchalance. She readily accepted my dismissiveness. It was easier for us both that way. She didn’t say the words I needed to hear. She didn’t say: “Rachel, I’m so sorry this happened to you.” She didn’t see deeper than the surface. She didn’t see I was in pain.

About a year ago, I invited my mom to a therapy session. I had written a memoir about my assault in hopes of helping other survivors and to help heal my own wounds. I asked my mom to read it. We agreed not to discuss what I had written until our session together. During my childhood, I had wanted to be in a closed room with her like a client, longing for her full attention. But she wasn’t my therapist in this room, and the room wasn’t cold and lonely like our living room. My therapist’s office is safe and warm. For the first time, maybe ever, my mom saw me in a new light, and was able to see some of her own inadequacies. Our relationship began to repair itself that day. We are still evolving, growing stronger with every honest conversation, of which we have many. I’ve recently told her how I felt about being on the cover of her book; I have learned to express all the pain and feelings the girl in the picture couldn’t.

I can look back at that book-cover photo and see something I’m not sure either Diana or my mom were able to see: determination.

Deep in those 9-year-old eyes, despite the hurt, was the look of someone who would eventually find her way, someone who would become hopeful and honest and free.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com