How a girl's inspiring 1860 letter to Abraham Lincoln ended up at Detroit Public Library

A previously unpublished letter written by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War recently sold to a private collector for $85,000. It sheds historical insight, a documents dealer said, on the president’s wartime strategy.

The newly discovered letter also highlights the value of writing things down, especially in an age of electronic communication, and is a reminder that Americans, including children, are fascinated by the former Midwestern president.

Almost every schoolchild in America learns Lincoln was born in a Kentucky log cabin. He died after being shot at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. And Illinois is the "Land of Lincoln," because that’s the state the 16th president represented when he served in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Lincoln traveled to Michigan at least one, maybe twice, during his lifetime and never during his presidency; and not only is Ford's luxury car brand named for the slain president, many artifacts connected to Lincoln's life can be found in metro Detroit.

More: 6 places in Michigan you can see President Abraham Lincoln letters, artifacts

There's the chair Lincoln sat in when shot, which is at the Henry Ford Museum; the Illinois courthouse where he practiced law, which was moved and reconstructed at Greenfield Village; a lock of Lincoln's hair at the Plymouth Historical Museum; and a letter, sent to Lincoln by Grace Bedell, a then-11-year-old girl, at the Detroit Public Library.

And that letter offers a very American lesson: Anyone, even little kids, can accomplish big things.

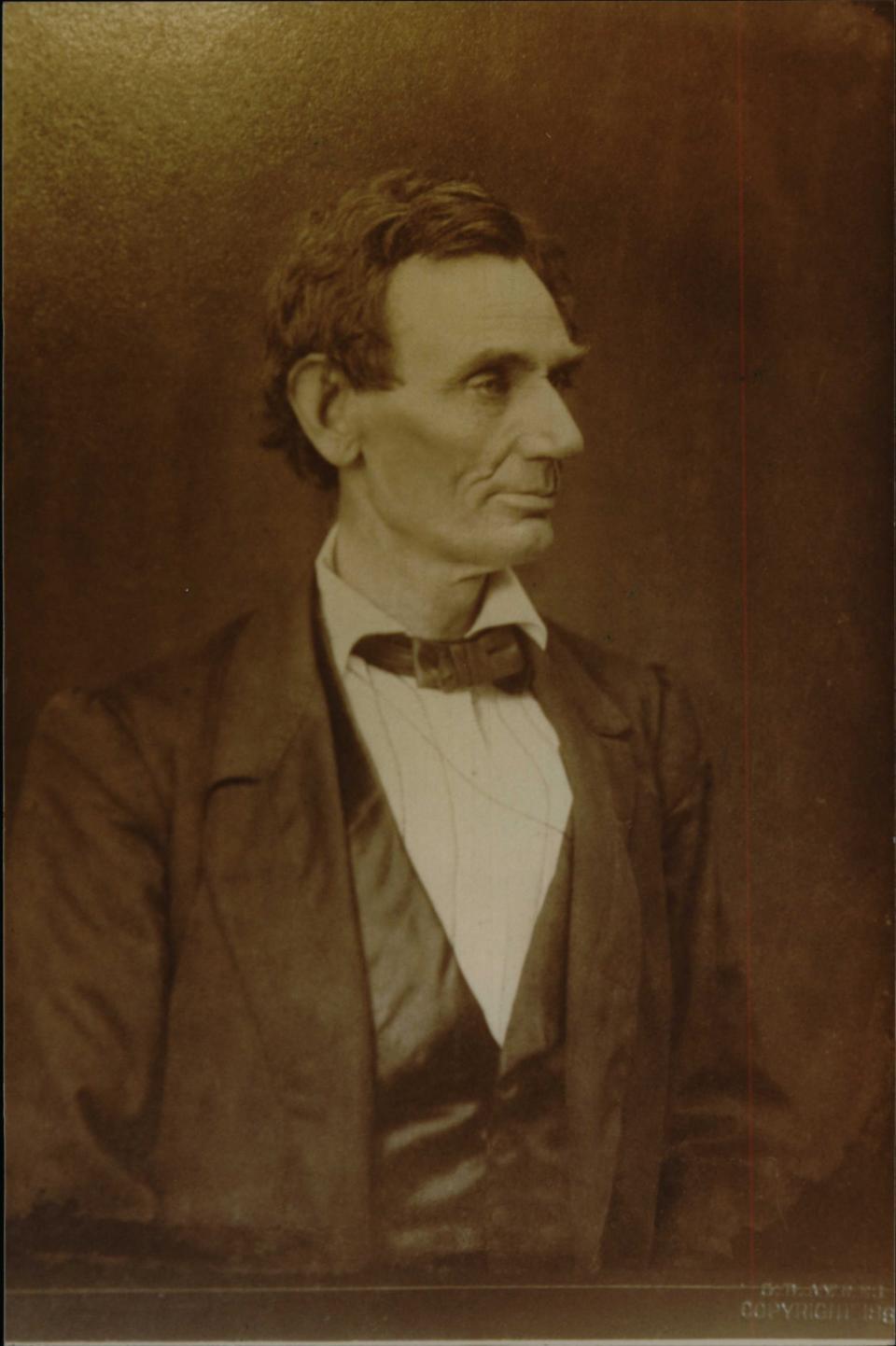

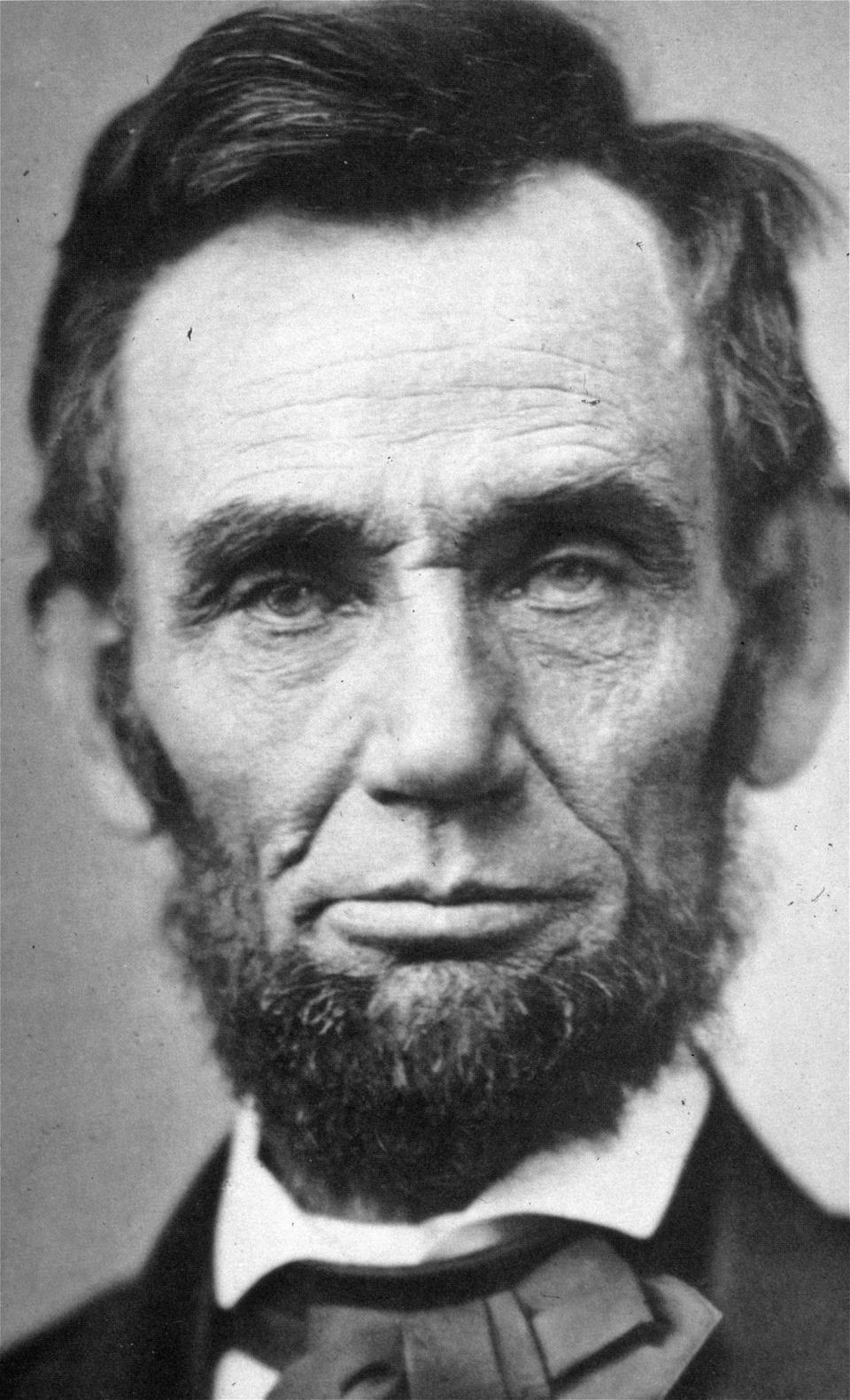

Historians — and schoolteachers — credit the note with inspiring the future president to grow out his facial hair, which Grace predicted would help him win the presidential election. Lincoln was, as it turns out, the first U.S. president to have a beard.

Winning a pivotal election

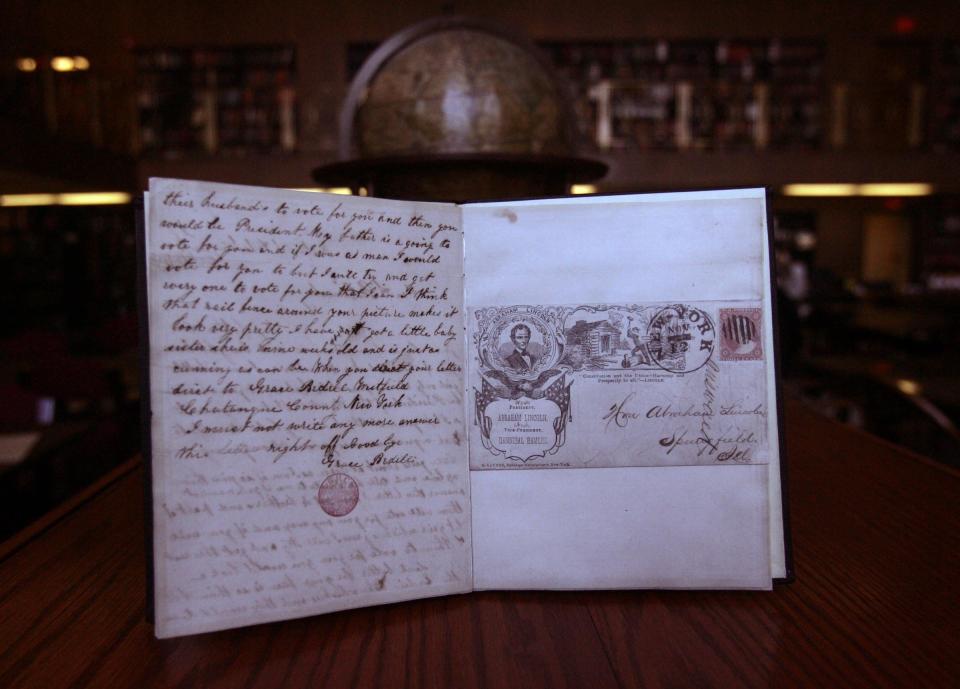

Even if you forget the letter's details, such as Grace’s name; where she lived, Westfield, N.Y.; and the historical fact, that, back then, women didn’t have the right to vote, there’s something inspiring about the old, hand-written document.

Grace inked the letter on Oct. 15, 1860, when Lincoln was locked in a pivotal race. He ran as the Republican nominee against three other men: Democratic nominee Sen. Stephen Douglas, Southern Democrat nominee John Breckinridge and Constitutional Union nominee John Bell.

The key political issues were slavery and states’ rights. Grace, however, focused on improving Lincoln’s looks.

In the letter, she said her father came home from the fair with Lincoln's picture and "Mr. Hamlin’s," referring to Lincoln’s running mate, Hannibal Hamlin from Maine. She told Lincoln she wanted him to become president. The problem, in Grace’s view, was that his clean-shaven face was too thin.

She said Lincoln "would look a great deal better" with a beard. At the time, only men — in some places, only white men — could vote. Grace made the case that a beard would benefit his campaign because women would "tease their husbands to vote for you."

And then, Grace made her letter more personal.

She added she had four brothers. Some of them, she told the president, were voting for him already, but "if you let your whiskers grow, I will try and get the rest" of them to support him. She asked Lincoln if he had any "little girls" her age and requested they write back if Lincoln could not.

A few days later, Lincoln replied.

'You can be president'

The future president addressed his letter, marked "private," to "my dear little Miss."

That letter is not at the Detroit Public Library, but what it says can be found online. Lincoln explained he had no daughters, only three sons, ages 17, 9 and 7, and a wife. As for the whiskers, he asked: "Having never worn any, do you not think people would call it a piece of silly affection if I were to begin it now?"

Silly or not, he grew a beard and won the election.

As he made his way to Washington in late February for his inauguration by train, he stopped in Westfield to look for Grace. He told the crowd at the train station about the "very pretty letter" he received. He also thanked Grace for telling him her idea.

"If she is here, I would like to see her," the Philadelphia Inquirer reported he said. She was, and she blushed. Lincoln gave her kisses, then said goodbye, making his way to the next stop: leading a nation that would soon become divided.

Then, almost 150 years later, Liz Bedell, one of Grace’s descendants, a then-staff member in the U.S. House of Representatives, said in a Library of Congress report that she had long heard stories from her grandfather about his Aunt Grace but "didn’t believe him."

But she did after she saw an exhibit that included a copy of Grace’s letter.

She wrote in the exhibition visitors’ log: "I cried my eyes out." She said her grandpa used to tell her: "You can do anything you want. You can be president. Why, just look at your great-great aunt Grace Bedell. She couldn’t vote, but she put pen to paper."

Who owns the letter?

How did Grace’s letter end up in Michigan?

That’s a story that with some controversy and conflicting versions of events.

In one version, George Dondero — an admirer of Lincoln, Royal Oak’s first mayor, and a former Republican Congressman — acquired the letter from Lincoln’s son, who asked him to return it to Grace Bedell, who was living in Kansas.

According to Dondero’s son, Robert Lincoln Dondero, Bedell then gave it to him.

The younger Dondero, after his father’s death, donated the letter to the Detroit Public Library, which makes it the property of the people. And that’s as the library has said the letter should be, in contrast to being hidden away in someone’s private collection.

The Detroit library has digitized the letter.

With an appointment, you can see the letter at the library. An appraisal in 2018 put its value at $100,000.

In another version of the story, the Free Press reported Bedell’s great-grandson, Duane Billings, said that according to family accounts, George Dondero visited Bedell with the letter, but she didn’t give it up willingly. He said that she told Dondero: "Now that it’s come back, I’ll never let it go."

Billings asserted that Dondero stole the letter.

And, he said, he believed the document should be in the hands of the family of its author.

Lincoln letters are rare

Either way, Max Maybee — who is 12, just a little older than Grace was when she wrote the letter, and has done two school projects on Lincoln — said he was not familiar with either letter that was recently sold or the one at the Detroit Public Library.

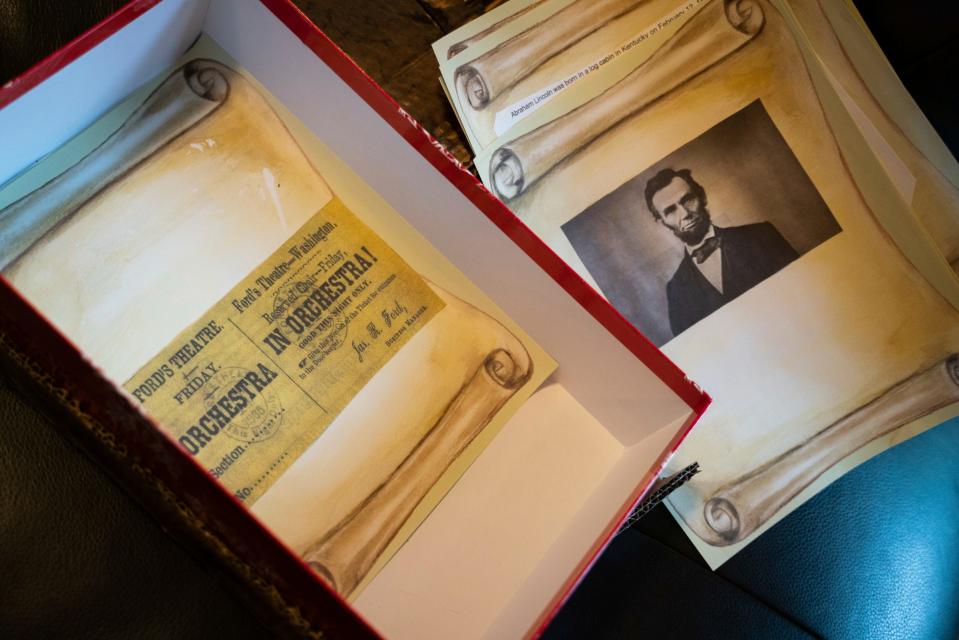

Max will be attending the University of Detroit Jesuit Academy in the fall. The Pleasant Ridge resident said he picked Lincoln to do research on because he wanted to learn more about him after completing a fifth-grade project, a poster of milestones in Lincoln’s life.

"We were told to choose a person and pretend you either knew them or were writing to them," Max said. "I already knew a bunch of stuff about Lincoln, but I wanted to learn more. I decided I could go into more depth with the research I already did."

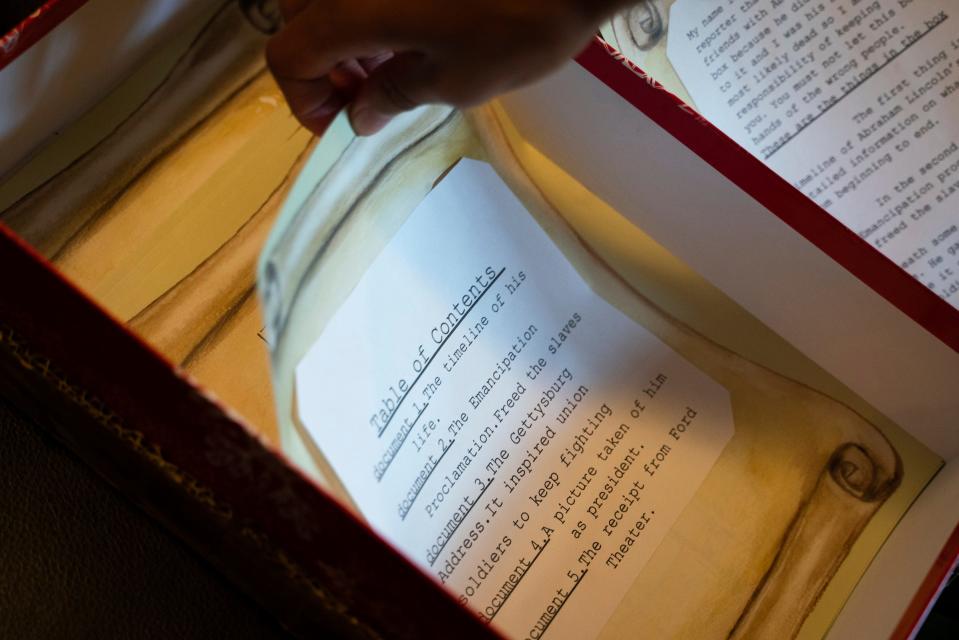

Max created an old-looking box that he filled with personalized re-creations of what could have been Lincoln’s mementos, including the Gettysburg Address, the Emancipation Proclamation, a list of important life events, a receipt from his ticket to Ford’s Theatre and two photos of a bearded Lincoln.

Max is still trying to wrap his head around what it would be like to live during a time when letter writing was as common as texting. He can make calls on an Apple wristwatch and play video games with his friends without even being in the same room.

But he said the project helped him realized the time it took for word to travel in those days is partly to blame for why long after the Emancipation Proclamation and the proposed 13th Amendment, folks in Texas hadn’t heard slavery was ending until Union troops arrived and told them.

The newly discovered Lincoln letter dated Aug. 19, 1861, "shows the use of the science of the day to protect Washington, and sheds light on political tensions," according to the Rabb Collection. Nathan Rabb — the Rabb Collection principal and a former journalist — added unpublished Lincoln letters are "increasingly rare."

The one-page document was purchased by a collector in the southeastern United States.

This summer, Max is attending a Detroit camp to learn how to make and manage money.

Max said $85,000 seems like a lot for a letter, even for something so rare and signed by one of America’s beloved presidents. These days, he added, people are more likely to send a text or email, but he is glad Grace's letter is at the library, a place where he — and other kids — can read it.

Contact Frank Witsil: 313-222-5022 or fwitsil@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: How a girl's 1860 letter to Abe Lincoln ended up at Detroit Library