Girls volleyball team was forced to play boys, one 6-3, in state final. The girls won.

INDIANAPOLIS -- High up in the bleachers, away from the raucous crowds below, coach Debbie Millbern sat with a notebook on her lap and pen in hand. She sat waiting. Waiting to see what she was up against. What her Muncie Northside volleyball team of girls was up against.

They had finished the season 25-1. They had sailed through the playoffs and, earlier that day, won both their state tournament matches to make it to the finals.

Millbern had sent her team back to the hotel for pizza, to watch TV, to rest before they played for the IHSAA girls volleyball state title that evening Nov. 15, 1975.

Indianapolis Colts news:What did Chiefs' Chris Jones say to Matt Ryan for game-turning unsportsmanlike penalty?

Sending them back to the hotel was a ploy, of sorts. There were boys in their midst. Boys getting ready to take the court.

Millbern didn't want her team to see that team, a South Bend Clay team with a 6-3 and a 6-0 boy on the roster; a team she knew they would face that night in the finals. Seeing what two towering boys could do on a girls'-height volleyball net -- six inches shorter than the boys' -- would likely put doubt in her team's mind. Half the battle in any sport is confidence.

"I wanted them to think," said Millbern, now Debbie Millbern Powers, in an interview with IndyStar this month, "that they could beat these boys."

As South Bend Clay ran onto the court inside Ben Davis High School, which was hosting the state finals, Millbern heard the crowd chanting below, she heard their relentless boos and taunts. At first, she felt sorry for the girls on the South Bend Clay team. But she knew they knew. The crowd's grumbling wasn't aimed toward them.

Their anger was firmly directed toward players Brian Goralski and Ed Derse, and the team's coach, Joan Mitchell, who was allowing boys to play on her girls volleyball team -- a twisted result of Title IX that had passed three years before.

"Brian was lean and muscular. He towered above the girls," Millbern writes in her book "Meeting Her Match." "As I watched him warm up, I realized that none of the boys we had practiced (against) during the week came close to his superior abilities."

Seara Burton:Everything we know about the Richmond police officer's shooting death

The crowd gasped as Goralski jumped and spiked the ball, his head and arms soaring above the net. "The ball resounded against the floor like a cannon blast," Millbern said.

She had no idea how her team would block him. Most of her players, even the tallest at 5-8, were lucky to get their forearms above the net.

Goralski's serve was intense, too. A powerful roundhouse jump serve that sped like a bullet over the net with a heavy topspin. As Millbern watched that game, she saw two girls get knocked down trying to receive a serve from Goralski. When he spiked, some of the players would cower rather than try to dig the ball.

Derse added another major challenge. He was not as talented as Goralski, Millbern said. "But he was 6 feet tall."

High up in those bleachers, Millbern jotted down strategies in her notebook and then she turned to her husband, Jim. "Holy crap," she said. "We're in trouble."

As Millbern left the gym to go back to the hotel to talk with her team before the state final matchup, she did the only thing she knew to do. "I prayed silently for a miracle."

'What's good for the goose is good for the gander'

Millbern's Muncie Northside team was the undefeated defending state champion. But as the 1975 season approached, the landscape of high school volleyball in Indiana had changed.

Title IX had passed in 1972. The law was intended to give girls and women equal treatment in educational and athletic programs that received federal funds. When it came to sports, girls were allowed to play on a boys team if the school didn't offer a similar program for them.

But on the flipside of Title IX, some boys started using the law to do the same -- to play on girls' teams if a boys' team wasn't offered. As girls started playing on golf and baseball teams, boys in some school systems started fighting for boys volleyball.

When it wasn't offered as a sport for them, they joined the girls teams. School officials didn't oppose.

"I think that they thought, well, what's good for the goose is good for the gander," said Priscilla Dillow, who was the volleyball coach at Ben Davis, the school's director of girls sports and the state finals host tourney director in 1975. "They just didn’t do anything."

So in 1975, coach Mitchell allowed Goralski and Derse to join her South Bend Clay team.

"The rumors started floating around as we got to sectionals and regionals that there was a team in South Bend that had allowed two boys to be on the team," Millbern said. "I didn't think anything of it then. But, by golly, there they were at the state championship."

Outside of Ben Davis in the parking lot that day of the state finals in 1975, fliers were handed out protesting the team with boys. Inside, protestors were in the stands.

"There was a noticeably large contingency of feminists who held signs announcing their disdain for South Bend Clay," Millbern said.

Go home Brian and Ed. No boys allowed. Joan Mitchell is a traitor. Hey girls...beat the boys!

"The boys, bless their hearts, they were only 16, 17 years old," Dillow said. "All they were wanting was to have teams and play volleyball.

"It was a tumultuous time in girls volleyball. It really was."

'What a liar I am'

After watching the volleyball prowess of Goralski, Millbern walked into a hotel room to talk to her team, to pump them up for their state final match against the boys. Millbern stepped over empty pizza boxes and started to speak.

Before she could say anything, the girls started asking: "Well, how good was he?"

"If an Academy Award for acting were to be given at that moment, I would have rightfully received it," Millbern writes in her book. She leaned against a door frame and crossed her arms. "Girls," she said with a smile, "we can win this. He's not nearly as good as the boys we've practiced against all week."

Millbern remembers her team jumping on the beds, screaming and giving one another high fives.

And she remembers as she walked out of the room, she muttered to herself: "What a liar I am."

As Muncie Northside arrived on the bus to Ben Davis, fans gathered to cheer them on. A female usher walked up to Millbern and handed her a program.

"Here ya go coach," the usher said. "Hope ya kill 'em."

The program had a picture of the Muncie Northside team on the front after winning the 1974 state championship. Sticking out of the program was a loose sheet of paper that read: An open letter to coach Joan Mitchell. You are a disgrace to girls sports. You are a traitor. If you really had courage, you'd put six girls on the floor to be worthy of winning the girls state championship. Congratulations, you have set girls sports back 10 years in Indiana...

Millbern stopped reading. There was nothing she could do about that now. The boys were on the opposing team and her girls had to face them.

She walked to the locker room and gave her team an enthusiastic talk, a rally. She could see her team was pumped up. But then, just as they were ready leave for the court, a player asked Millbern if she had a poem. "Yeah, where's our poem?" other players chimed in.

Hurricane Ian:Storm track shifts south to Sarasota, but all of Florida faces 'significant' impacts: Live updates

The year before, as Muncie Northside was ready to begin its state championship game, Millbern had read a poem she had written to the team.

The night before at the hotel, Millbern had written a poem for this year, too, but it was one she hadn't planned on reading. She feared it would get her team down. Now, she had no choice.

Millbern pulled the folded piece of paper out of her jacket and began to read: The date today is the 15th of November. It will be a day in your life you will always remember. Yes, Titans, you became one of the final eight and now have a chance to win another state. You have more experience than any team here so as far as I can see you have nothing to fear. You have tons of ability, skill and poise and you've scrimmaged this week against the boys. But Brian and company are waiting through that door. They are confident that against them you'll rarely score. Regardless of the outcome, I know you'll play your best. And I love you like daughters, I sure can attest.

The girls hung their heads. Some started crying. Millbern began to panic. She hoped her poem hadn't been a mistake.

She wanted her team in good spirits, happy and aggressive. She knew they would need that and more to make history that night -- to become the first girls team to beat a team with boys in the Indiana volleyball state finals.

'Keep the ball away from Brian'

Muncie Northside stepped onto the court and began warming up to cheers. As the South Bend Clay team ran out, they were greeted with "the loudest booing and jeering I had ever heard," Millbern said. Obscenities were shouted at Goralski and Derse, as well as other jabs.

You guys need to shave your legs. Do you wear a bra under that blouse? How's it feel to beat up on girls?

But as the first game of the best of three series played out, the boys didn't beat up on the girls. Goralski was tall enough to spike the ball from the back row, behind the 10-foot line, meaning he was a hitter in all six positions. He could be set anywhere on the court.

But Goralski alone wasn't enough. Muncie Northside beat South Bend Clay soundly, 15-6, after a 5-5 sophomore for Muncie Northside served eight straight points, including three aces.

In the huddle after that first game, Millbern kneeled to look at her girls: "Stay focused and let's do it to 'em again. This is our night. Not Brian's."

But in the second game, "Brian's sheer physical presence overtook us," Millbern said. At one point, he scored four straight kills. Muncie Northside lost 14-10. There was a running clock rule in 1975 that ended the game if a team didn't reach 15 points first.

In the huddle, Millbern came up with a new strategy. "I can tell Brian is getting tired," she told her team. "Let's not even try to block him at the net anymore. When they set him, I want all six of you to back off the net, get low and be ready to dig up everything." She grabbed a program and diagrammed the new defensive formation.

"Make them work hard for every ball," she said as the players ran onto the court.

The third game started out in a heat, tied 7-7. Then Muncie Northside took a 12-8 lead. But soon Goralski's skills overpowered them and South Bend Clay was up 13-12. Millbern called a timeout.

"Now is when we make history," she shouted to her team in the huddle. "This is where we dig to our deepest core. Keep the ball away from Brian and let's end this thing."

"Back on the court, it was as if they had a sudden infusion of ice in their veins," Millbern writes in her book.

One of her players slammed a hard hit to Clay's back court and another stuffed a Clay spike to their floor. Muncie Northside took a 14-13 lead with two seconds left on the clock.

In those final seconds, Muncie Northside's setter lofted a high ball to a player, who rolled a soft hit toward the net. The ball hit the top of the net and rolled along the top of the tape. "It seemed to suspend there forever," Millbern said. The crowd was on its feet and players on both benches stood up clasping hands.

The ball dropped onto the sideline of Clay's court.

Muncie Northside had beaten South Bend Clay 15-13. The girls had beaten the boys in the state finals.

As Millbern's team exploded, she walked to South Bend Clay coach Mitchell, shook her hand and told her "good match." As Millbern walked by Goralski, he was leaning over, exhausted. She patted him on his back: "You played one heck of a match."

Although Muncie Northside had won, the women protesters in the stands marched out of the gym in single file after the match. They were making a statement. They disagreed with the IHSAA allowing boys to play. Taunts were still being shouted at the male players.

When South Bend Clay's team got to the parking lot, they found their van covered in shaving cream, soap and wax, according to a 1975 letter-to-the-editor in the Indianapolis Star written by South Bend Clay school officials, titled "Rudeness Shocking." The tires of the van had been deflated and obscenities covered the vehicle.

"This letter does not describe half of the incidents displayed by other schools toward Clay," the letter read. "There isn't enough room for everything, and most of the incidents were too bad to be told in the newspaper."

Dillow said she felt bad for the boys playing during that time. None of it was their fault, after all.

But the IHSAA was fine with the situation, especially after the boys team lost in that 1975 state finals.

"What happened was the IHSAA said, 'What the heck? Girls can win against boys," said Millbern. "But if we would have lost that match? The IHSAA might have changed their ruling a year earlier."

What was the harm? Nothing in 1975, but 1976 changed everything

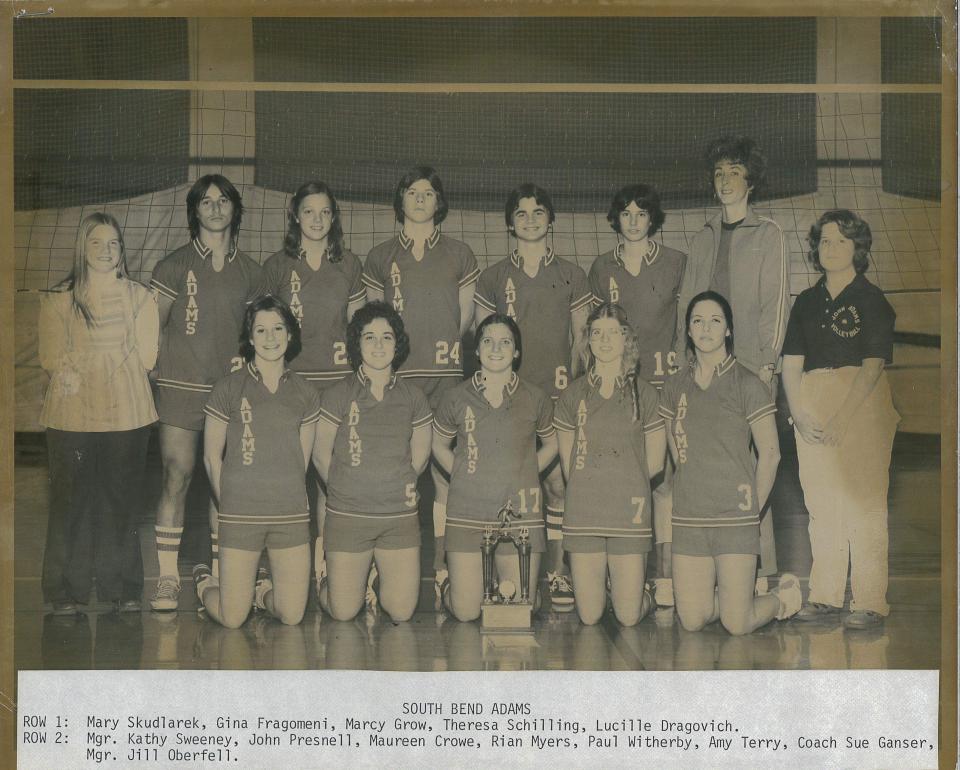

That ruling Millbern is talking about is one the IHSAA issued a year later, banning boys from playing girls sports. It came after the 1976 state volleyball finals when South Bend Adams, with three boys on the roster, beat a team of all girls from Fort Wayne Concordia.

South Bend Adams finished the 1976 season undefeated 21-0 and won the state championship 15-11, 15-9, playing John Presnell, Rian Meyers and Paul Witherby.

"That one team has three boys on it. That's three out of six or 50% of the team that is boys," Pat Roy, director of girls athletics for IHSAA told the Indianapolis Star days before the state tournament in 1976. "Many of the girls on the other teams are upset about it and so are some of the coaches."

The IHSAA's commissioner Phil Eskew sided with the boys. "The court has ruled that a girl may play on a boys' team if that sports is not available to her," Eskew told IndyStar in 1975. "So it seems only fitting that a boy should have the same privilege."

Before the 1976 state tournament, Roy said she expected an appeal might soon be filed to ban boys from girls teams in Indiana. But that didn't happen soon enough for Fort Wayne Concordia. And that was a shame, said Bob Michael, the team's assistant coach in 1976.

Michael's team of girls had every right to think they might win state. They were 22-1 heading into the finals. They had been annihilating the competition. In the semifinals against Chatard, Fort Wayne Concordia won 15-2, 15-7.

"I don't know that anybody has ever gotten beat that bad," Michael said.

And then the state final match came. "And I can absolutely tell you that (South Bend Adams) played three boys a majority of the time against us," Michael said.

There were other problems besides the boys, he said. Fort Wayne Concordia had played the afternoon games. South Bend Adams had played in the morning.

"We had a half hour between the conclusion of the semifinal match and the start of the state finals match, 15 minutes to basically go collect ourselves and 15 minutes to warm up," he said. "Still, I think we gave them a run for their money."

Fort Wayne Concordia scored nine and 11 points against South Bend Adams and Michael, to this day, believes they should have scored more. He wonders if he made a mistake.

"The only thing I ever regret is we never told them that (playing boys) didn't (give them) an out," he said. "I think in their minds, they thought, 'Well, we are playing three boys.'"

But when Fort Wayne Concordia lost that state finals match, there was no animosity, Michael said. The girls were gracious in their loss.

"After the match was over, they came up, shook my hand, and said, 'All we wanted to do was get here to play against you,'" John Presnell, a member of the South Bend Adams team, told IndyStar. "I thought that was great."

What happened that night in 1976 wasn't right, but "that's what it was," Michael said. It couldn't be changed.

Unless, if a year earlier, the Muncie Northside girls had been beaten by South Bend Clay's team with boys, Millbern said.

"If we had lost, I think 1975 would have been the year boys stopped playing girls sports."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: After Title IX, Indiana girls volleyball team was forced to play boys