'Giving power to the community:' $22M drug prevention effort targets Calgary youth

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

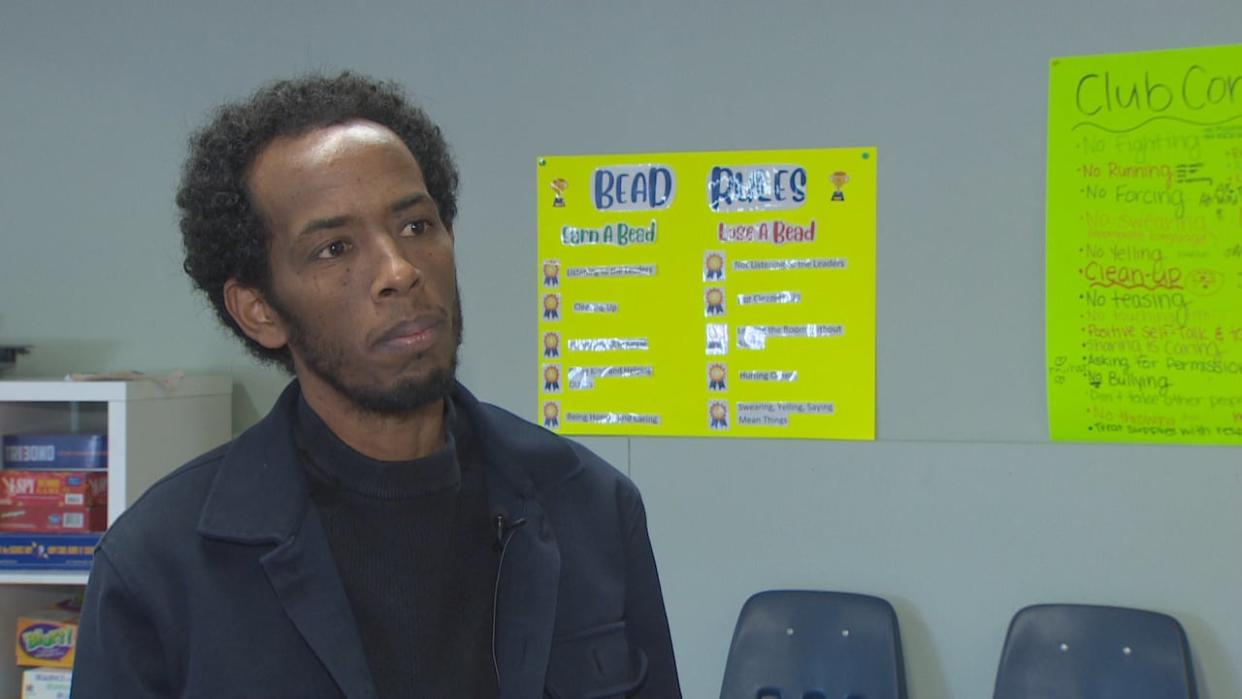

Despite the outreach programs scattered across Greater Forest Lawn, Surafiel Kibreab has been watching high school students in his community fall through the cracks.

He says many are newcomer kids who come to Calgary after five to six years in a refugee camp. They get put in school according to their age rather than their ability to learn, and they struggle to keep up.

Local agencies are trying to help. But "there is a very high rate of substance issues, mental health, drop out from high school. It affects their mental health; it affects their confidence and makes it hard for them to survive."

A piece of the solution is missing. But now Kibreab hopes he's on track to find an answer.

Kibreab is part of a new, $22-million, drug-prevention program from the United Way of Calgary and its partners. Called Planet Youth, it's an approach driven by locally-gathered data that aims to bring lessons from Iceland to cities around the world.

It's about getting parents and community leaders all listening to youth — acting on that insight, measuring to see if the action is working, and repeating.

Here in Calgary, it's being rolled out in Greater Forest Lawn, Shawnessy, Thorncliffe and Saddle Ridge, plus there's an Indigenous stream.

Lessons from Iceland

The approach is based on the dramatic changes seen in Iceland.

Twenty years ago, Iceland had such high rates of youth drunkenness that people considered it dangerous to walk in downtown Reykjavik after the bars emptied at night.

Soccer fields like this one in Iceland are used heavily, thanks to subsidies for after-school activities provided by the Icelandic government. (Brian Goldman)

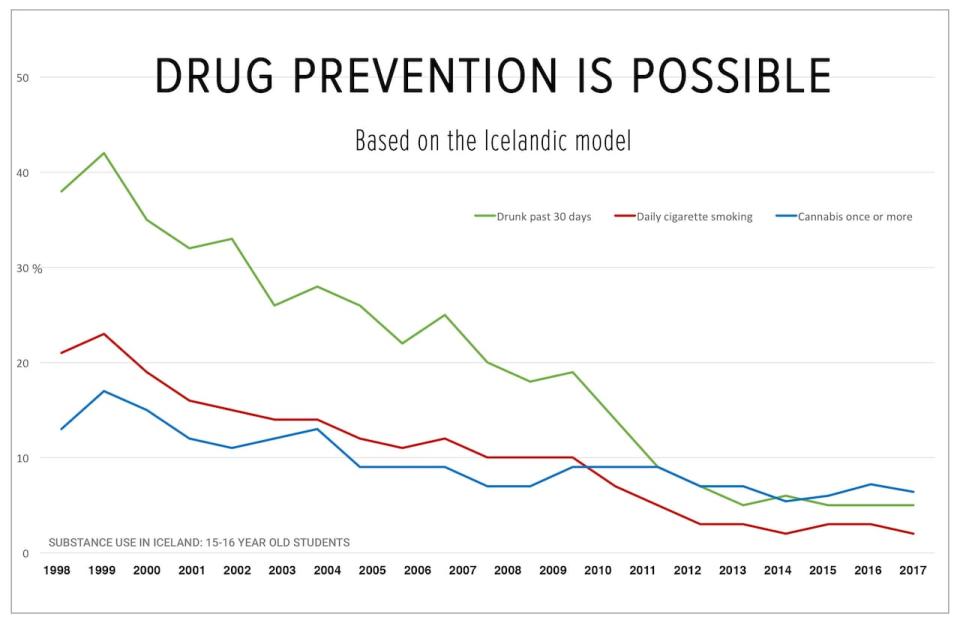

So researchers systematically surveyed youth, ages 15 and 16, to understand what risk factors were influencing so many to make those choices.

Then they met with a coalition of youth, parents and community groups. Together, the group decided to address the risk factors by beefing up free recreational activities for high school students, bringing in a curfew and running campaigns to convince parents to spend more quality time with their teenagers on weekends.

Over two decades, they kept surveying teens annually to figure out what was working and build on it.

After 20 years, the number of Icelandic youth who said they got drunk in the past 30 days was down to five per cent, from 42 per cent in the late 1990s, according to the Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis.

The researchers involved rebranded as Planet Youth and are now involved in prevention efforts in 16 countries and hundreds of cities. The team provides data analysis and guidance for teams in each community.

Researchers in Iceland survey Grade 10 students annually to assess their risk factors and track whether specific interventions are working. The data is published by the Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis. (European Cities Against Drugs)

Robin Katrick is the Planet Youth regional director for North America and says she hopes community members will get involved and inspired.

"To be successful and sustainable, you need the whole community rallying around it," she said. "That's the really cool thing about this program is that you really can make a difference by just listening and then having the motivation to work together."

So what needs to be in place to ensure success? A couple of things, she said.

You really can make a difference by just listening and then having the motivation to work together. - Robin Katrick, Planet Youth

One is to release the youth survey data back to the community as quick as possible — ideally in just six weeks. The second is to get that community buy-in so that all the key local players are at the table, looking at that data, listening to the youth and trying to find solutions.

The third is having sustainable funding so that worthwhile efforts actually get time to show their potential.

And the fourth?

"You have to have patience," Katrick said. "It doesn't happen overnight. I know a lot of people see that chart from Iceland where the numbers have dropped, but that has taken over 25 years to see those really low rates of substance use."

Building trust in Greater Forest Lawn

Originally from Eritrea, Kibreab moved to Calgary in 2017. He was hired by the Trellis Society, one of the United Way's core partners, to build support for the project in Greater Forest Lawn.

So far, he says, the high school students have been telling him they need employment help, recreation facilities and safe spaces to be after school and on weekends. Community members have been excited about the project, but also a little leery.

The Trellis Society building in Pembrooke, in Calgary's Greater Forest Lawn. (Mike Symington/CBC)

"The model is about preventing those youth from falling through the cracks, and finding out what they love to do," he said.

"People, especially in the Greater Forest Lawn area, they don't just accept any program that comes because they come and go. In one year, two years, a new program will disappear.

"We've been promising them that this program is going to be for a long term and the result will be a long-term result," he said.

"We're giving the power to the community; we're giving the power to the youth and the parents," Kibreab added. "Everyone in the community is going to work on it: the parents, the school, the lawmakers and everyone in the community. And the results will guide us and show us where we're heading."

The team will start by surveying local Grade 10 students in the new year. They'll survey again in two years to measure progress.

Kimberly Van Patten is leading the Indigenous stream of the local Planet Youth effort for the United Way. (Mike Symington/CBC)

In other cities, interventions have included leisure access passes, creating new sports and art or other leisure activities, and parent cafes or parental agreements to increase family involvement in the young people's lives.

A parallel Indigenous effort

Kimberly Van Patten is leading the Indigenous stream for the United Way with Miskanawah. She grew up in Rocky Lane, near High Level in northern Alberta, and is a member of the Tallcree First Nation.

It's such a small community, most of her high school courses were online. But she knows what kept her going and on a good path.

"The people around me, the supportive and caring adults — so my parents, my family, the teachers at school, my coaches — that supportive network got me really motivated and saw that potential in me and gave me confidence."

Already, what she's hearing from the Indigenous youth involved as advisors on the Planet Youth Indigenous stream is that they need the same thing, and something that focuses on their mental health and well-being.

Jason Lidberg of the United Way of Calgary says the $22 million raised so far will cover six years of the Planet Youth effort. (Mike Symington/CBC)

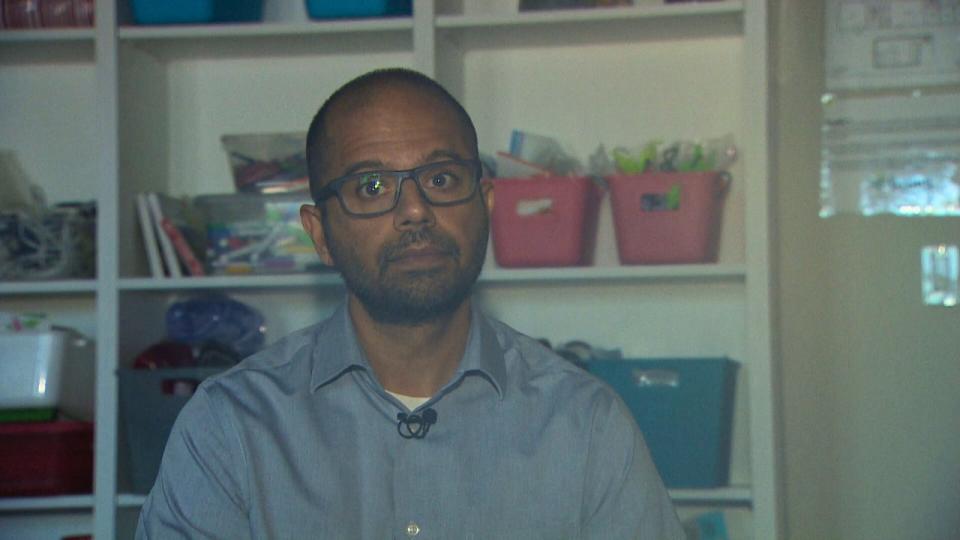

Jason Lidberg is the Planet Youth manager with the United Way, seconded from the YMCA. He said the $22 million raised so far came from individual Calgary residents and local corporations. Their target is $26 million for the project, which is meant to be enough for the first six years.

Donors were motivated to find another way to respond to the growing opioid and toxic drug crisis.

"We're looking at this issues in Calgary and saying, what can we do — understanding there is a need for interventions and responding to the crisis — but what could we do to get upstream of this and prevent issues from happening?" he said.

"What can we do to support youth, to build the kind of communities that we want to have in Calgary, where it's a great place to be a kid and to raise kids as well?"

In Canada, other jurisdictions working with Planet Youth include Timmins and Timiskaming, and Lanark County in Ontario, and several municipalities in New Brunswick. Planet Youth is also working with the Public Health Agency of Canada, which is hoping to select new communities in early 2024.