Giving thanks, expressing hope: presidential wishes at Thanksgiving

The most beloved hymn of Thanksgiving bids us to gather together to ask the Lord’s blessing. So do perhaps the most poignant, and unjustly forgotten, presidential remarks in our history, many delivered at times of national turbulence and tumult.

Just months after his election, George Washington — who had led his beleaguered Revolutionary War troops in Thanksgiving rituals outside Valley Forge, Pa., in 1777 — began the tradition of presidential proclamations at this season.

In the autumn of 1789 he urged the young nation to pause in thanks and to express hope that “our national government [will be] a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed.”

For more than two centuries, Washington’s successors have promulgated Thanksgiving proclamations, urging the country to reflect on its bounty, as Theodore Roosevelt did in 1901 when he said that “no people on earth have such abundant cause for thanksgiving as we have,” and to dedicate itself to preserving what Rutherford B. Hayes described in 1879 as “the supremacy and security of the great institutions of civil and religious freedom.”

These proclamations surely are among the most neglected of presidential remarks. They haven’t had the staying power of inaugural addresses (“ask not what your country can do for you”) or calls to action (“a day which will live in infamy”) or remembrance ("we cannot hallow this ground”).

But the Thanksgiving addresses are instructive, reflecting how presidents marked the holiday in their own periods of challenge.

For decades the date of Thanksgiving varied from state to state, but Abraham Lincoln, heeding the plea of magazine editor Sarah Josepha Hale that the day of our annual Thanksgiving be “made a National and fixed Union Festival,” placed the holiday firmly in November. And so amid the national distress of the Civil War, Lincoln in 1861 became the founding father of the modern Thanksgiving.

Perhaps now, after the political strife of the 2020 election and amid a galloping pandemic, we might take comfort in the long-ignored remarks.

I recommend to [Americans] that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.

— Abraham Lincoln, 1863

These remarks from the 16th president came when the nation was quite literally, and geographically, divided. They were issued amid a Civil War that produced by far the most deaths of any conflict undertaken by Americans at a time when the survival of the country was anything but assured.

This proclamation, moreover, was issued for a Thanksgiving that would occur only days before his Gettysburg Address, in which he refined this theme and expressed his devout hope that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

But this proclamation also foreshadowed Lincoln’s remarks at his second inaugural address, when he dedicated the country “to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” And in his 1863 Thanksgiving remarks he spoke of “the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy” — a theme he would return to in mordant terms in his 1865 inaugural address.

That custom [of Thanksgiving] we can follow now even in the midst of the tragedy of a world shaken by war and immeasurable disaster, in the midst of sorrow and great peril, because even amidst the darkness that has gathered about us we can see the great blessings God has bestowed upon us, blessings that are better than mere peace of mind and prosperity of enterprise.

We have been given the opportunity to serve mankind ... by taking up arms against a tyranny that threatened to master and debase men everywhere and joining with other free peoples in demanding for all the nations of the world what we then demanded and obtained for ourselves.

— Woodrow Wilson, 1917

These Thanksgiving remarks came seven months after Wilson led the country into World War I. Wilson, the son of a preacher, was one part scholar and one part politician, one part idealist and one part visionary.

This proclamation reflects the tones he struck in his war message in the spring, when he said that “our object now ... is to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power." Two months after Thanksgiving he would issue his Fourteen Points that he hoped would shape the peace that followed what became known as the Great War, themes that he presaged in his Thanksgiving proclamation.

Inspired with faith and courage by [the 23rd Psalm], let us turn again to the work that confronts us in this time of national emergency: in the armed services and the merchant marine; in factories and offices; on farms and in the mines; on highways, railways and airways; in other places of public service to the Nation; and in our homes.

— Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1942

FDR would deliver three wartime Thanksgiving proclamations but this one, nearly a year into Americans’ involvement in the conflict, has special resonance. Though U.S. forces prevailed that month in the Battle of Guadalcanal, the outcome of the war was still uncertain. The titanic and tragic struggle around Stalingrad had just begun. American troops were fighting in Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa.

Roosevelt still found occasion to ask the country to join him in expressing thanks “for the bounties of the harvest, for opportunities to labor and to serve, and for the continuation of those homely joys and satisfactions which enrich our lives.” A man who was able to conjure optimism even during the darkest moments of the Depression and war also glowed with hope and confidence at Thanksgiving.

We are deeply grateful for the bounties of our soil, for the unequaled production of our mines and factories, and for all the vast resources of our beloved country, which have enabled our citizens to build a great civilization. We are thankful for the enjoyment of our personal liberties and for the loyalty of our fellow Americans.

We offer fervent thanks that we are privileged to join with other countries in the work of the United Nations, which was founded to maintain peace in a troubled world and is now standing firm in upholding the principles of international justice.

— Harry S. Truman, 1950

Thanksgivings for Truman posed a peculiar problem. In 1947 his administration — in the first White House decision announced on the new technology of television — began a program of Meatless Tuesdays and Poultryless Thursdays designed to share food with Europe, which was threatened with famine. That made the traditional consumption of turkey and of the president’s much favored pumpkin pie (which required milk in its production) problematic. Truman in 1950 marked his sixth Thanksgiving as president by having his turkey, along with candied sweet potatoes, baked stuffed peaches, buttered peas and braised celery, on the Wednesday before the holiday.

But for Truman — whose presidency overlapped the last months of World War II and the beginning of the Korean War — this was no ordinary Thanksgiving. Five months earlier the nation had entered battle in Korea under the flag of the United Nations. A month before Thanksgiving, troops from China’s People’s Liberation Army had poured into the conflict, creating some of the fiercest fighting of the war.

We give our thanks, most of all, for the ideals of honor and faith we inherit from our forefathers — for the decency of purpose, steadfastness of resolve and strength of will, for the courage and the humility, which they possessed and which we must seek every day to emulate. As we express our gratitude, we must never forget that the highest appreciation is not to utter words but to live by them.

— John F. Kennedy, 1963

This proclamation, full of the language of national purpose that was the Kennedy idiom and the soundtrack of the New Frontier, was issued 18 days before the president was assassinated. Kennedy was born 41 miles from Plymouth Rock and was an admirer of the rhetoric of the Pilgrim leader John Winthrop. The holiday would be celebrated three days after his funeral.

Our real blessings lie not in our bounty. They lie in those steadfast principles that the early pilgrims forged for all generations to come: the belief in the essential dignity of man; the restless search for a better world for all; and the courage — as shown by our sons in Viet Nam today — to defend the cause of freedom wherever on earth it is threatened. These are the eternal blessings of America. They are the blessings which make us grateful even when the future is uncertain.

— Lyndon B. Johnson, 1965

Johnson made this proclamation as 184,300 American troops were serving in Vietnam, a conflict that already was becoming the preoccupation of the president — and the nation.

The context is poignant. Two days after Thanksgiving came two significant events: an antiwar demonstration by 35,000 protesters, the first mass expression of dissent over the war, and a Pentagon report saying that troop levels in Vietnam should be increased to 400,000 in the next year and perhaps to 600,000 the year after that. A Gallup poll that fall showed that 64% of the American public approved of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. By the next Thanksgiving that figure would drop by about a quarter.

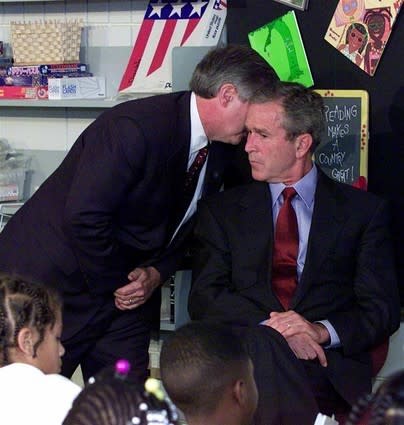

As we recover from the terrible tragedies of September 11, Americans of every belief and heritage give thanks to God for the many blessings we enjoy as a free, faithful, and fair-minded land.

Let us particularly give thanks for the selfless sacrifices of those who responded in service to others after the terrorist attacks, setting aside their own safety as they reached out to help their neighbors.... And let us give thanks for the millions of people of faith who have opened their hearts to those in need with love and prayer, bringing us a deeper unity and stronger resolve.

— George W. Bush, 2001

For a Thanksgiving shrouded in grief and introspection, these words, coming more than two months months after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington and the downing of an airliner in a Pennsylvania field, reflected the country’s distress at a time of great national turmoil. Already American troops were engaged in combat in Afghanistan.

The country, meanwhile, was gripped in a debate that weighed security against civil liberties. Bush would face stormy days ahead, but his Thanksgiving proclamation hit high notes, and just the right notes.

In his last year as president, Barack Obama, in prescient remarks applicable to our time, said that “the American instinct has never been to seek isolation in opposite corners; it is to find strength in our common creed and forge unity from our great diversity.” He went on to cite that first Thanksgiving, in Plymouth, noting that “these same ideals brought together people of different backgrounds and beliefs, and every year since, with enduring confidence in the power of faith, love, gratitude, and optimism, this force of unity has sustained us as a people.”

We cannot be drawn together this year, even as we might yearn to, after the great divisions of the presidential campaign. But we might recall the year 1958 — a time, unlike our own, of relative tranquility — when Dwight D. Eisenhower issued an unusually lyrical Thanksgiving proclamation. He spoke of how Americans “rejoice in the beauty of our land; in every brave and generous act of our fellow man; and in the counsel and comfort of our friends” and he remarked upon how “we deeply appreciate the preservation of those ideals of liberty and justice which form the basis of our national life and the hope of international peace.”

To these many words we, in our time of national testing, might add a single word: Amen.

David M. Shribman is a special correspondent.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.