The Glory of Spain : A Treasure Trove That Tells a Story

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE O ne of the most inspiring, instructive, and beautiful exhibitions in the country now is The Glory of Spain: Treasures of the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, which I saw at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts before the conceited axis of big government, airhead media, and lemming academics quarantined the world to fight a virus that, if and until there’s a vaccine, isn’t going away. It took the Spanish Empire centuries to dissipate vast wealth we wasted willy-nilly in a few weeks. In times like these, great art from the past gives perspective and teaches resilience.

It’s a traveling show of highlights from the Hispanic Society in upper Manhattan, one of the greatest but least-known museums in the country. The Society owns and displays the best collection of Spanish art outside Spain in a distinguished building that’s part Beaux-Arts, part Moorish revival, part plateresque, and thoroughly fantastic.

I usually don’t like highlights shows. They’re often fluff. This exhibition, though, is different. It’s a solid history of Spanish, Portuguese, and Spanish-American art from around 2400 b.c. to a.d. 1900, a sweep, I know, but Spanish art is different, and that sweep makes for a good story.

It’s an unusual institutional history as well. For pleasure, too, it’s a trove. The art is the best, as is its interpretation in Houston’s spacious, welcoming galleries.

The Hispanic Society is the life’s work of Archer Huntington (1870–1955), heir to a railroad fortune, who discovered Spain and Spanish culture as an inquisitive teenager. With laser focus and big bucks, he assembled an unparalleled collection of art, books, photographs, and manuscripts, with the purpose of establishing a museum and research center. He paid for the building on 155th Street and Broadway, on the site of John James Audubon’s farm. The place opened in 1908. The collection is enormous, with about 7,000 paintings, watercolors, and drawings, 200,000 books, 250,000 manuscripts from the eleventh century to the present, and great sculpture, ceramics, metalwork, textiles, furniture, jewelry, and glass.

The rub is “155th Street and Broadway.” When Huntington selected the Society’s location, he assumed, as did everyone, that the development of the Upper West Side as prime residential, commercial, and cultural space would continue northward and not sputter and stop around 96th Street.

People from Manhattan? Talk about provincial. Most think that north of 96th Street lies the Red Planet, and Martians might grab their Hermès handbags or spit on their Ferragamo shoes. I’ve been to the Hispanic Society a hundred times over the years. It’s on the edge of Spanish Harlem and perfectly nice, and the subway is across the street. But it’s not the Museum Mile, and it’s not midtown. It’s a serious academic place and not a social hot spot. It has struggled for visitors and donors.

In the last few years, it has started to find its place in the sun. It’s raising money to renovate its buildings. Philippe de Montebello chairs its board. The Houston show has gone to the Prado in Madrid and to museums in Mexico City and throughout America, giving the Hispanic Society the attention it deserves. I hope this means that rich people in Manhattan will give to the Hispanic Society, where big money is needed and transformative, rather than to the Met or MoMA, which are loaded — too loaded, in my opinion. If you want to make a difference in the arts, the Hispanic Society is the place to go, checkbook in hand, and don’t be stingy with the zeros.

There are many ways to interpret a show that starts with prehistoric ceramics and Roman jewelry — Spain wasn’t an outpost of the Roman Empire but an integral, thriving component — and ends with Joaquín Sorolla. Houston focuses, smartly and appropriately, on cultural crosscurrents. Celtic, Moorish, Jewish, Christian, Roman, French, Flemish, Italian, and indigenous American blend to produce an aesthetic that’s recognizably and uniquely Hispanic.

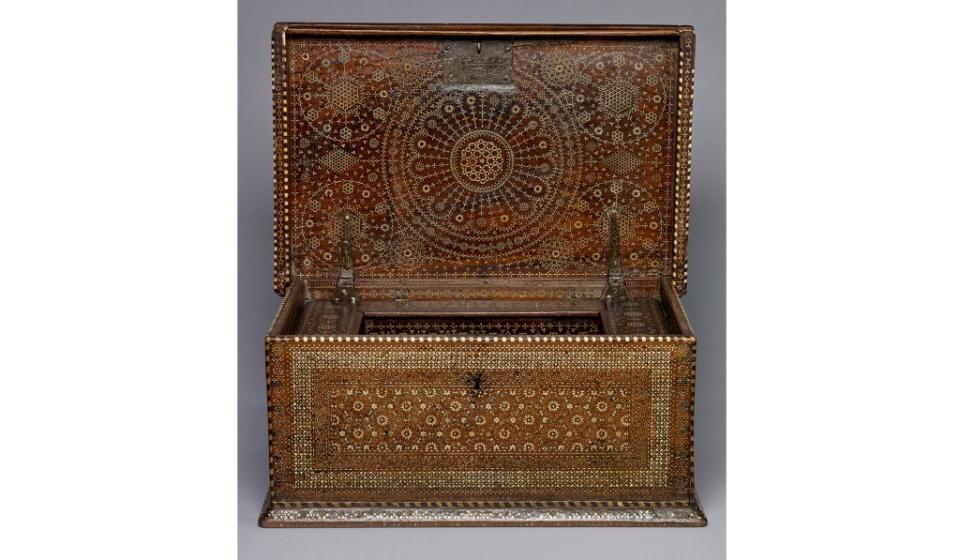

A core characteristic of Spanish art is pattern, and that feeling for intricate pattern comes from the 700 years of Moorish rule over the peninsula, starting in 711 and ending in 1492, when Ferdinand’s and Isabella’s Christian armies kicked the Moors from Granada, their last redoubt, and ended the Reconquista. Valencia was the center of Hispano-Moresque lusterware, with all-over geometric patterns and palettes of blue and gold. A splendid Mudéjar chest, of walnut and inlaid ivory, from around 1525 is decorated with a dense though ordered sequence of circles and rows of stylized starbursts surrounded by multiple borders. It’s from Barcelona and shows the durability of Moorish style after the Reconquista ended and the dissemination of the style to a part of Spain guided mostly by taste in neighboring Languedoc, in France.

Palaces and mosques in Córdoba and Granada, the Alhambra the most famous, formed Spain’s aesthetic long after the Moors left. The plateresque style, Spain’s contribution to Renaissance architecture, takes classical-revival forms and slathers them with abstract geometric shapes, cartouches, string courses, and garlands.

Huntington collected maps in abundance, and the Society has some of the Spanish world’s best maps, nautical charts, and atlases. Here, Huntington proves he’s a man of his time and class. Americans have long had a feeling of part fascination and part contempt about Spain. Spain was Catholic, and America was Protestant, so tension was elemental.

For early Americans, English-acculturated, Spanishness was always a culture anathema. In the 19th century, tensions were more political and territorial. Bordering Anglo America was Mexico, with which we warred and routed in the late 1840s. Cuba was an issue. Earlier, with the Louisiana Purchase, we might have bought the Louisiana territory from France, but France had owned that big chunk for only a few years. Spain had owned it for centuries.

By the 1890s, the much-truncated Spanish Empire was a lumbering bankrupt. The Spanish–American War killed it, finally, leaving America with Spain’s overseas colonies and establishing us as a new empire, whether we called it that or not. Huntington and his class of industrialists, tastemakers, movers, and shakers saw themselves as inheritors of the charge to rule the world, not in the Spanish way, but rule of the world nonetheless. Americans were the new explorers and adventurers, and Huntington’s interest in maps, beyond their aesthetic beauty, reflected that hegemonic role.

Huntington wasn’t the only American to collect Imperial Spanish portraits. Down the road from the Hispanic Society, at the Met and the Frick, are Diego Velázquez portraits of Philip IV and his circle, collected by Huntington’s potentate contemporaries. One of the great paintings in the Houston show, and a Huntington home run, is Velázquez’s Portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares, from 1625–26. Velázquez (1599–1660) was the Sevillian savant brought to Madrid by the young Philip IV as the court painter.

Aside from portraits of the king and his brother, Don Carlos, Velázquez’s portrait of Olivares was his first opus. Olivares (1587–1645) was the king’s prime minister and a ruthless, savvy politician and aristocrat. The portrait’s done in Velázquez’s early style: crisply finished, unadorned backdrop except for a shadow and drapery, direct engagement between subject and viewer, and lots of black. His hands, silk suit, and wool cape are beautifully textured.

Velázquez spent 40 years in Philip’s court, not only as the chief court painter but as curator of the king’s collection and as the chief decorator of the king’s palaces. His style changed over the years. As a curator, Velázquez knew the king’s collection of work by Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, and Rubens visited Spain not only to paint but as a diplomat from the Spanish Netherlands. Velázquez’s palette grew warmer, his brushstroke far freer, and, after a long stay in Rome, from 1649 to 1650, his faces fleshier and more dynamic. His portrait of the Italian Cardinal Pamphili, from 1650, is in the Houston leg of the tour. It’s not a full-length portrait but a more informal bust. His face is far creamier and the cassock a medley of red.

Velázquez’s portrait of Olivares, like most of his early work, has a sculptural quality, firmly modeled with distinct contours. Convincing lifelike form was important. These characteristics in painting descend from sculpture, and in Seville, Velázquez’s home, sculpture, not painting, was the most desired form of religious art. Sculpture from southern Spain was usually painted in vivid colors, making saints as lifelike as possible. Pedro de Mena’s Saint Acisclus, from about 1680, shows how enduring that tradition was. Acisclus was the patron saint of Córdoba and a young Roman martyr. He was a handsome guy, or so Mena’s bust suggests, but with a furrowed brow and worried eyes. No wonder — beneath his chin we see his ear-to-ear slit throat. Talk about lifelike.

The theme of amalgamation informs work by El Greco (1541–1614) and Bartolomé Murillo (1617–1682). El Greco spent most of his career in Toledo but combined an early style derived from painted icons in Crete with Venetian color and paint handling, along with firm Roman form, to make something unique. Murillo was Seville’s premier painter at a time when the city was Spain’s link to the European business world. His patrons were Spanish, German, French, Italian, and Dutch, and his style can best be called international and broadly appealing.

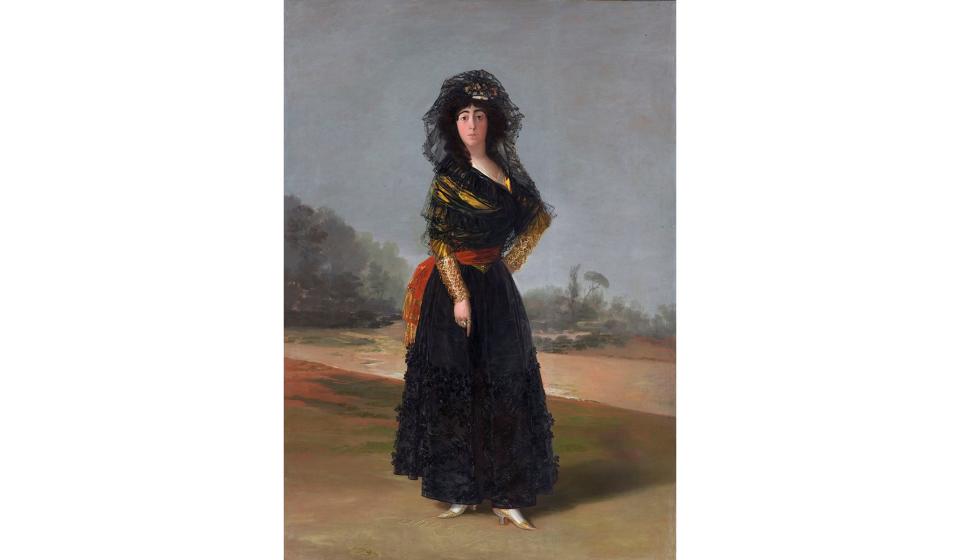

There are many show stoppers but Goya’s Duchess of Alba, from 1797, is the picture above the title, and the duchess herself would have it no less. Maria del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva Álvarez de Toledo y Silva-Bazán (1762–1802) had charisma, a star quality that’s part Joan Crawford and part Ava Gardner, having “not a single hair on her head that does not awaken desire.” That was the French ambassador’s take, and by all accounts she was born a cougar. She is dressed in fashionable maja style and stands on the banks of the Guadalquivir River, which ran through her Andalusia estate.

The Duchess of Alba title is one of the oldest and most prestigious in Spain. The family was then Spain’s richest, and even when the 18th duchess died in 2014, she was the most heavily titled aristocrat in the world as well as a rich socialite and bon vivant without peer. Goya painted at least three portraits of the 13th duchess, for whom his feelings were fraught, to say the least. Her husband had died the year before. Goya, then 50, spent parts of 1796 and 1797 staying at her palace in Sanlúcar.

Looking directly and commandingly at the viewer, the duchess points to the inscription “Solo Goya” traced in the dirt. She wears two rings, one etched with the word “Alba,” and the other with the word “Goya.” Goya kept the portrait and later painted over the word “Solo.” He later wrote that she tormented him with “lying and inconstancy.” She appears in one of his Caprichos etchings, called “Gone for Good,” in the same black dress, flying away on a cloud of witches. So, this isn’t an Ozzie-and-Harriet-type relationship.

Biography can be a distraction, though. It’s a gorgeous painting and looks it in Houston’s pitch-perfect arrangement. Goya was a brilliant painter and printmaker but his drawings — more than a thousand exist — are as beguiling, and more so since they’re the secret Goya. He drew what was on his mind, using not pencil but sweeps of washes, different chalks, crayon, and ink.

There’s a nice selection of drawings in the gallery from 1796 to the end of his life. They certainly show Goya’s capacity for ridicule — Majas Fighting, a Majo Observing, from 1796–97, shows two women in full wrestle, one beating another with a shoe very much looking like the duchess’s — but they also show he can convey form and weight with one passage of wash and a few inky lines. Some of Goya’s best prints are there, too. Houston arranged the work nicely to make a mini-retrospective.

The Duchess of Alba’s silk and lace are black, so the look’s moody, even grave, but they’re luminous and ethereal, too, with delicate dash. Her face doesn’t say “Come hither.” It says “Get your ass over here and kneel,” and that’s bossy. Goya then softens her with flirty flounces and enough transparency to tempt the viewer to wonder what’s underneath. She wears a hot-red sash, because she’s hot and knows it. Glittering gold embroidery suggests armor, but it’s textured, and lacy garlands on her dress say “austere and forbidding” since they’re black, but they’re soft and filmy, too.

The gallery’s sleek gray wall color is an inspired choice. It augments the subtle gold and red sparkle in The Duchess of Alba and in The Portrait of Manuel Lapeña, from 1799, the other full-length Goya portrait on view. The space is titled “Enlightenment Spain,” and there are enough Goyas spanning 30 years to tell us the Spanish Enlightenment was like no other. Cool reason had a moment but entitlement, cruelty, passion, and insanity jostle with reason. Goya believes they win the day.

The show has good things from Latin America and South America. It concludes with work by Joaquín Sorolla (1863–1923). His big, colorful, light-drenched pictures are lovely and sensual.

In every respect, it’s a great show. The Hispanic Society sent its best, and its best is the world’s best. I’m delighted to see this great institution — a museum and a superb library — get the recognition. Houston’s arrangement is inspired as well. I love its galleries. They’re big, with high ceilings, and they tend to be nice, open spaces that are infinitely flexible.

The Hispanic Society show is in a 14,000-square-foot space. There are some temporary walls, but the curator kept that feeling, that blessing, of openness. With such a handsome, big space, Houston could take the many sculptures and ceramics in the exhibition and display them in cases in the round, and that’s always best. They have breathing room. With so much beautiful space, juxtapositions are not only possible — they’re splendidly available and used. It was a joy for me to see the many conversations that different objects and media were able to have. Textiles, ironwork, ceramics, jewelry, and even paintings harmoniously blended, reinforcing colors and forms they share.

I loved the show and hope the Houston museum reopens with dispatch so that this city of rich, buoyant diversity can savor a concert of art. Its run in Houston has been extended to September 7.