Conservative Michigan lawyer uses extremism, God to find policy wins, critics say

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

LANSING — Amid a chaotic time for Michigan Republicans, a small group of lawyers and activists are beckoning conservatives back to their roots: local control and God.

Lawyers Dave Kallman, William Wagner and several colleagues think they might have a solution to a politically fraught future for conservatives: legal representation for conservative local governments and training sessions that feature a controversial blend of good governance practices and “godly statesmanship.”

The actions come as the Michigan Republican Party navigates a potentially devastating crisis. Almost eight years after former President Donald Trump descended his golden escalator, the Michigan GOP lost every statewide lever of power they’d grown accustomed to controlling for the better part of a half-century. The formal party is rife with infighting, donors are closing their wallets and no one appears capable of unifying passionate factions. To many, something needs to change.

That’s where Kallman and his friends come in. As one prominent Michigan Republican put it, they are helping create a much-needed conservative bench of talent in the state.

“I think the most important thing is getting back to the basics and getting back to true conservatism,” said Tom Leonard, a Republican former Michigan House speaker and attorney general candidate.

“You look at this last election cycle, while it may not have gone well for conservatives statewide … they did pick up a majority on many local units of government boards, as well as school boards. And I think there’s a very good opportunity for education on those levels, and essentially building a farm system for conservatives across the state.”

Most local government leaders are already conservative, according to the findings of a long-standing survey by a University of Michigan expert. Kallman and his colleagues believe taking on local boards as clients while training other town and county leaders could pave a path to instituting policies they support.

Kallman is known for his work with the Great Lakes Justice Center, an organization founded by Wagner that takes on some of the biggest conservative legal battles in Michigan. Wagner is a former federal U.S. magistrate and currently leads the Wagner Faith & Freedom Center at Spring Arbor University.

But recently, in the dusty corners of township halls and under the fluorescent lights of school board meeting rooms, Kallman and others are trying to help institute at least a modicum of their view of conservative policy one day at a time. His firm already represents the Ottawa County Commission, a GOP-held board enacting controversial policies garnering both pushback and praise.

While there are logistical hurdles, experts suggested they have a real avenue to finding success at the local level. Any effort to wrest away power from a party apparatus firmly in Trump’s grasp faces long odds. And some Republican leaders acknowledge they’ve lost the battle for Michigan, at least for its top elected posts in the near future.

But this group of passionate and polarizing figures believe the war for the hearts and minds of local communities is far from over.

Important context: Donald Trump put his prestige on line in 2022 election — and it didn't work

‘We won. Now what?’

Chances are you haven’t heard of Kallman. But you know his work — it tends to inspire or make people irate.

Opponents suggest the longtime Michigan conservative lawyer and his organization are extremist, far-right activists trying to shoehorn the law into a murky mix of religion, perceived superiority and conservative bigotry. They point to his fight against expanding LGBTQ+ protections and clients or colleagues who espouse offensive causes.

Supporters love him. They view him as a defender of parental rights standing in the breach against the tides of liberalism.

An affable man, Kallman views himself as a champion of the underdog, an advocate for freedom from government overreach. Raised a Baptist, he doesn’t deny his own religious worldview and how it shapes his work. But he repeatedly says he’ll defend anyone if he thinks their rights were violated, even if he vehemently disagrees with their personal beliefs. For example, he successfully represented Western Michigan University student athletes fighting a COVID-19 vaccine regulation, while also personally being vaccinated.

During a Saturday event in March at a Lansing-area church, Kallman explained how he planned to put his philosophy to work.

“While everybody understands we did not have our red wave at the state level (in the 2022 election), at the local level, we did have a red wave in many areas around the state: Ottawa County, many school boards and a lot of county commission boards, township boards. There’s a lot of turnover there,” Kallman said, according to video of the session posted to YouTube.

“I know that because we’ve been getting calls from people who are on those boards and in those positions, kind of going ‘Uh, we won. Now what? What do we do now?’ ”

Those calls prompted Kallman to double his relatively small legal team in order to represent counties and school boards across the state. In addition to the Ottawa County Commission and the Allendale Public Schools Board in west Michigan, Kallman’s team represents the Onaway Area Community Schools Board in northern Michigan. They are in talks to potentially represent many more, Kallman said.

Go deeper: Is Livingston County following the roadmap Ottawa Impact created?

They also offer training sessions, called the “Go Local Community Influencer Conference,” for municipal leaders in search of “practical tools for servant-statesmanship.”

The training is supposed to equip eager but green officials with information that will make them more effective, Kallman and Wagner told the Free Press. But it goes beyond simple lessons on good governance: they include calls to proselytize.

The sessions are a mix of the Constitution and Christianity, combining Robert’s Rules of Order with “a heritage of godly statesmanship.” During the Lansing sessions, speakers promoted so-called “traditional marriage,” attacked abortion and extolled the virtues of their views on Christianity.

Kallman and Wagner said they are not trying to promote a Christian government.

“(The training is) not with the intent that only Christians can run for office. That's silly, you know, I mean, stuff like that. That's ridiculous,” Kallman said.

Yet some of their messages are sure to be met with a wide degree of skepticism and pushback.

“There is no separation of church and state when it comes to the Constitution, there really isn’t. And anybody who says that, they don’t know what the Constitution says,” said Jack Jordan, a Kallman attorney who represents the Ottawa County Commission, at the Lansing training event.

Ultimately, how local leaders use guidance from these sessions could be problematic. The law and Constitution bar overt special treatment of any specific religion, noted Richard Schragger, a law professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.

“When a local official says there is no such thing as ‘separation’ in the Constitution, they usually mean that the word ‘separation’ isn’t in the document. But that’s just a rhetorical trope. Disestablishment requires that no official at whatever level of government seek to ensconce a particular religious view, theology, or practice as the official government religious view, theology, or practice,” Schragger said.

'He’s finding different ways to promote the conservative agenda'

At 6-foot-6, Kallman is a big guy. Nowadays, it can lend the 67-year-old gravitas in the courtroom. But in his youth, it was most beneficial on the basketball court.

A graduate of Williamston High School, Kallman’s academic and professional future depended solely on where he could play basketball. Kallman jokes he crammed four years of college into five, stretching out his eligibility to play.

“I had four minors, I ended up with a business degree. I went to school because I had to, to play ball. I wasn’t thinking about anything other than having a good time in college,” Kallman said, laughing.

Eventually graduating from Northwood University, he decided to pursue law. Working during the day and attending Cooley Law School at night, Kallman earned his law license in 1982.

Opening his own firm, Kallman took every kind of case that came in the door. In relatively short order, he landed what is arguably his biggest.

Known as People v. DeJonge, the roughly decade-long legal saga centered on a state law requiring children be taught by someone with a certificate. The case still offers a glimpse into Kallman’s legal strategy — never stop fighting, and take cases even if others think they’re unwinnable.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, Kallman represented Ottawa County parents who home-schooled their children. Court records show the parents wanted a “Christ-centered education.” Because the parents were not certified teachers in accordance with the law at the time, both were charged with and convicted of a crime.

Kallman appealed. After a series of losses and new appeals, the Michigan Supreme Court issued a 4-3 decision, and Kallman won. The deciding vote: Justice Charles Levin, a member of the well-known Democratic political family.

“I mean, total opposite end from me. I didn't even argue thinking that we had a chance to get him. And actually one of the Republicans that I thought we would have went against us,” Kallman said.

“I learned a long time ago, you never really know. If we can make a really good argument, you can persuade. That's the whole point of the process.”

He has tested that theory more than once. Through some of those cases, he met Wagner. Dividing his time between his firm and the Great Lakes Justice Center, Kallman and colleagues took on cases challenging the state’s interpretation of religious freedom, blasting pandemic mandates and arguing in support of theoretical abortion prosecutions.

Amid the flurry of election lawsuits following the 2020 presidential contest, Kallman was one of the first attorneys to elevate Mellissa Carone. His use of an affidavit from Carone, who worked at what was then the TCF Center on election night, ultimately dovetailed into a haywire Michigan legislative hearing with Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani and a subsequent spoofing on "Saturday Night Live."

Leonard defended Kallman’s actions after the 2020 election. He noted Kallman supported his own 2022 Republican campaign for attorney general, opposing ultimate nominee and election denier Matt DePerno.

“(Kallman) plays a very important role in our legal process, because he is willing to step up and take cases that are not always politically popular, despite the fact that the law is on his side,” Leonard said.

Beyond lawsuits, Leonard championed Kallman’s training sessions and his decision to represent local governments.

“(Kallman) is not giving up. He’s finding different ways to promote the conservative agenda,” he said.

At various points in recent years, Kallman took other cases where he also needed to squint to see a path to victory.

When he agreed to represent a handful of conservative county prosecutors who wanted to fight for the right to prosecute people under a long-dormant state abortion ban, the odds were against him. For years, public polling in Michigan and elsewhere showed a vast majority of adults supported at least some abortion rights. More than 600,000 people signed petitions that helped put a proposed amendment to the state Constitution expanding abortion rights on the ballot.

He felt like he faced similar odds representing a pair of businesses accused of civil rights violations for refusing to serve LGBTQ+ people.

“We all knew what the outcome was going to be, I’ll just say that. But does that mean I’m not going to take a case and not argue what I think is the correct constitutional interpretation? Or the abortion case, and trying to protect the two prosecutors that we represented, because that was a real abuse of power?” Kallman said.

‘They are twisting how to interpret the Constitution’

State Rep. Emily Dievendorf, D-Lansing, first encountered Kallman’s work in 2018: They were the head of a local LGBTQ+ advocacy organization and Kallman represented parents and students fighting Williamston Community Schools policies that created student protections pertaining to gender identity and sexual orientation. They remember Kallman’s Great Lakes Justice Center attempting to gain support based on “misinformation and bias,” creating a situation they said was dangerous for local LGBTQ+ students.

At the time, Kallman told the Lansing State Journal he and his clients, “have no beef with any students,” but rather thought the policies were unfair.

This type of argument obscures a more ominous tactic, Dievendorf argued.

“They are acknowledging there needs to be a manipulation of truth; it speaks to exactly how much they aren’t representing the average American right now, or what the average American wants to see happen in terms of how we treat our friends and neighbors,” Dievendorf said in a recent phone interview.

“They are twisting how to interpret the Constitution, what protections we do and we don’t need and they’re trying to codify that into law.”

Ingham County Clerk Barb Byrum agrees, calling Kallman and his colleagues extreme and more focused on policy wins than improving communities. A former state lawmaker and outspoken Democrat, she also outlined her view of the dangers of ideological organizations offering training to local officials.

There are plenty of state organizations that already help train new school board or county commission members, Byrum said. She also noted other groups, not necessarily affiliated with Kallman and Wagner, are offering comparable training on election procedures. It’s creating a hot mess for clerks and generally politicizing what should be a nonpartisan process, she said.

“Local governments are typically servant leaders. They’re your neighbors, they’re behind you in the school pickup lines. They’re members of our communities,” Byrum said.

“What they’re doing is shifting the focus away from service to their neighbors (to) partisan, political agendas.”

Carol Siemon, a Democrat and former prosecutor in Ingham County from 2017 through 2022, has a very different perspective on Kallman. After interacting with him frequently on cases related to child protection, she said she thinks he is a man of integrity.

“While our personal values and politics differ widely (about as widely as possible), we have always gotten along well and he is a man of honor,” Siemon told the Free Press in an email, noting Kallman endorsed her in 2016.

“David was sincere, hard-working, respectful, and clear in his beliefs without being abrasive. I knew he was a conservative Christian and he knew I was a confirmed secular humanist, and it never detracted from our relationship.”

While the subject matter and his opponents can be heated, Kallman typically keeps his cool. Humor and a generally positive disposition set him apart from many conservative contemporaries. He’s fervent, but not foaming at the mouth. He’s passionate, but not hostile.

This concept, of vehemently disagreeing without being disagreeable, is one Kallman hopes to use and spread.

Now as a lawmaker, Dievendorf recently participated in a legislative committee hearing where Wagner testified. They saw him speak out against a bill, ultimately approved in a party-line vote by the House, that aims to expand protections under hate crime laws. Wagner and others argue it's too vague, suggesting it may open someone up to a felony conviction for using an incorrect pronoun.

“Whether you’re coming from the left or right on these issues, it makes a person guess whether or not their conduct is criminal or not. Which leaves, in the hand of either a conservative or a left-leaning prosecutor, too much arbitrary discretion on how to charge a case,” Wagner said during a mid-June hearing, offering some specific proposed changes to the bill.

“I hope you fix it. I appreciate what you’re doing, because every person, is in our view, is made in the image of God and therefore is worthy of being treated with dignity and respect.”

While the legislation does create new protections based on someone's gender identity, it does not specifically reference pronouns. In order to break the proposed law, someone would need to use physical violence, threats, intimidate someone or destroy their property, according to the bill. Democrats and other supporters of the bill say Wagner's pronoun suggestion is a gross mischaracterization of the legislation.

Dievendorf said these conservative lawyers might be cordial, but they are adamant that they're using a tactic to obscure work that is extreme, manipulative and dangerous.

“How politely they treat me in the hallway is not going to be what leads me to trust them. It’s going to be their actions and their intent. And they’ve made that clear, time and time again,” Dievendorf said.

“I would hope that my actions would be interpreted as a reflection of my values. And I do think that that lens needs to be used for other folks and organizations.”

‘We’re ambassadors for Jesus Christ’

An extension cord is doing a lot of work in Wagner’s presentation.

He’s dragging it across a stage on a Saturday in March at Grace Bible Church in Lansing, positioning it near large poster boards that show iconic images of the White House, U.S. Capitol and U.S. Supreme Court. It’s a not-so-subtle metaphor, one the local officials watching his presentation are supposed to remember whenever they question whether they have the authority to take a certain action.

They have power, vested in them by the Constitution, to take sweeping action, he argues.

“We’ve got to be fiercely unafraid to speak the truth at the local level, because we the people have given you the local government official the power to do that. You are the voice,” Wagner said.

Then, he takes a turn.

“That is the place where the heart of Jesus has to be shown,” Wagner says. “We’re not talking about a religious government. We’re talking about a perspective that this world desperately needs.”

This blend of constitutional basics and the importance of Christianity in governing permeates throughout the event. Wagner, who also runs a religious and legal nonprofit called Salt & Light Global, joined Kallman and a slew of others.

Every session at the Lansing training included multiple references to Christianity. A former mayor of Potterville, a small city about 15 miles southwest of Lansing, heralded the power of prayer, telling attendees she helped start a prayer group that eased organizational dysfunction.

James Muffett, leader of Citizens for Traditional Values, was the most explicit. Leading the session on a “heritage of godly statesmanship,” he repeatedly told attendees why it was so important for Christians to both spread the gospel and run for local office.

“We’re teachers. We’re also combatants. But most of all, we’re ambassadors for Jesus Christ. … God has called us to sit in the seats so that darkness does not sit there,” he said.

Wagner said they are not telling local officials to prioritize Christianity over any other religion. Rather, Kallman and Wagner want local leaders to channel their interpretation of Christian principles in approaching the challenges they face in their official roles.

It takes a close read to see the distinction Kallman and Wagner are trying to make. The law lives in nuance, but nuance dies in politics. Increasingly, there’s little room in the white-hot arena of public discourse for subtle distinctions, especially on issues like religion. When people hear a government official talk publicly about religion, it can set off alarm bells.

Wagner is adamant he and Kallman are not advocating for a theocracy.

“Do I want them to take their Bible into their local government meeting? No, I want them to take their constitution into their local government meeting,” Wagner said.

“If they read their bible in the morning, then they know that they’re not supposed to lie. I want them to go into the meeting, to carry the Constitution and then not lie.”

'You have a lot of people who are just shaking their heads'

No Republican won any marquee Michigan statewide election after Trump secured the state in 2016. Thanks to a combination of redistricting and a political push to the far right, they’re going to have an even tougher time grabbing legislative seats.

In addition to their statewide failures, the party relinquished control of both the state Senate and House. It’s the first time in 40 years Democrats control the executive, legislative and judicial branches of Michigan government.

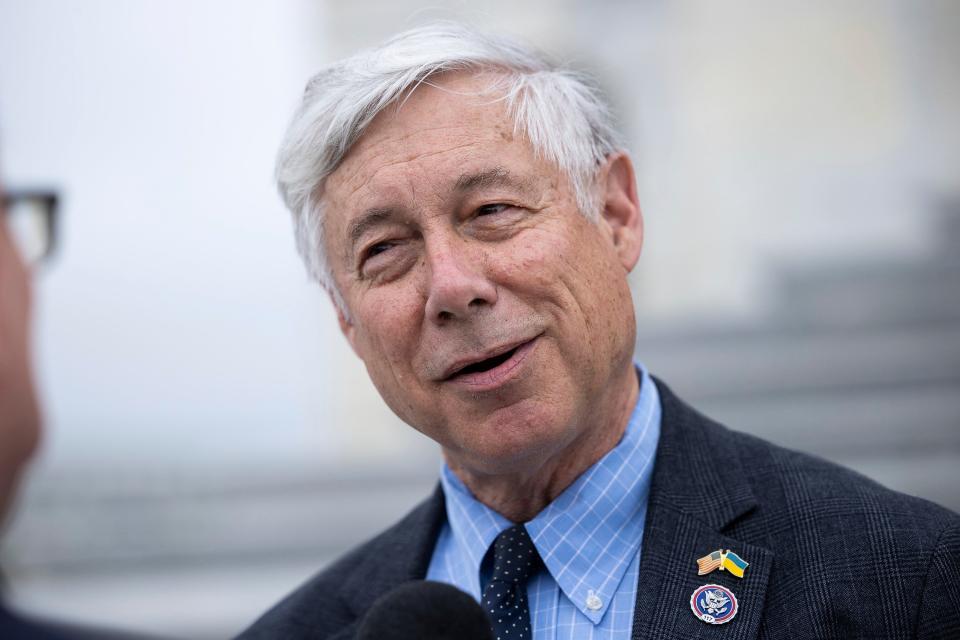

“It’s going to take at least another election cycle before Michigan politics here on the Republican side really gets straightened out. You saw that in the election last year, you look at that with our new state chair. You have a lot of people who are just shaking their heads, saying ‘let’s just wait until things really bottom out,’ ” said Fred Upton, former longtime west Michigan GOP congressman who declined to seek reelection in 2022 after voting repeatedly to impeach Trump, during an early June panel with reporters on WKAR’s “Off The Record.”

Republicans lack some of the most important ingredients to policy and political wins at the state level: cohesion, money and a unifying figure.

However, these factors become far less important in local races. The decisions made locally frequently have a larger impact than any action by Congress or the state Legislature. Local officials determine police pay, whether to create new taxes, policies on school books and the logistics of running elections.

“In the political science literature, there's a lot of dispute about the impact of partisanship at the local government level, with many people saying it’s just not as big of an issue at the local level as it is at the state and federal level. But more recently, other researchers are starting to dispute that and say, well, in fact, partisanship is a very big factor in local government as well,” said Tom Ivacko, executive director of the Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy at University of Michigan.

For years, conservative organizations zeroed in on state legislatures. Traditionally, red states already held majorities in statehouses. Acknowledging this power advantage, groups proposed model legislation that could more quickly and more effectively spread conservative policy positions nationwide. While Washington dithered, state lawmakers took action.

Now, with Democrats back in control in Michigan, in theory, there’s an opportunity for a similar strategy at the local level.

Ivacko and his team survey local elected leaders every few months. They’ve done the work for years, offering a glimpse at how township supervisors, mayors and commissioner leaders feel about their government.

Since 2009, roughly six out of 10 top leaders of these government entities self-identify as Republicans, Ivacko found. Despite statewide trends that saw Democrats win the governorship and help deliver Joe Biden to the White House, conservatives continue to control key local positions.

It’s a stable, relatively untapped network that, in theory, could be used to spread policy, Ivacko said.

He noted even with a potential increase in partisanship, much of what local governments do — paving roads, maintaining water systems, etc. — do not inherently lend themselves to political advocacy from either party. That’s one of several obvious limitations to creating some sort of national conservative playbook for local governments, said Matt Grossman, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research at Michigan State University.

Grossman notes it’s relatively easy to come up with model bills for legislatures. Finding something similar that works at the local level can be difficult: while state constitutions and laws vary some, local charters and other founding documents can differ widely.

There’s definitely a national movement to pass conservative policies at the school board level, Grossman said. But he questioned its efficacy.

“It's one thing to have a movement that is based in elections and based in conservative media traction, versus is there a movement with specific legislative priorities that is trying to achieve those through model legislation. I think right now those things are still a little bit divorced from one another,” Grossman said.

The fact there are more municipalities with conservative leadership also means there may be more conservative-inspired policies from these governments. That’s not inherently wrong, Grossman noted, pointing to the demographics of the regions these elected officials represent.

“It’s better if elected officials know both Robert’s Rules and all that, but also that they hear from people who’ve been effective at policymaking. I guess I would shy away from the pure, ‘something nefarious is afoot here,’ ” Grossman said.

Kallman and his colleagues firmly believe their intentions are pure. And they hope, with a bit of guidance for local elected leaders, communities across Michigan will agree.

Contact Dave Boucher: dboucher@freepress.com, or on Twitter @Dave_Boucher1.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan lawyer Dave Kallman wants to save GOP's conservative ideals