The Gold Miner Who Hiked Into Colorado’s Worst Blizzard on a Mission for Love

By 7 p.m. exactly 120 years ago, Loren Waldo was dead. No one can say that for sure because he was alone. But if you lie down in the snow for just five minutes as if you’d fallen there, unable to ski through a sub-zero night, you’ll know.

I’m writing this from the inside of a 150-year-old cabin at the very top of Boreas Pass, a gale-prone gap on the Continental Divide in Colorado. It’s below zero, and if not for the wood stove at my feet and the down bag that I will zip into soon, I’d be as dead as Waldo on the anniversary of his death: February 11.

I skied up here to see the winter day that Waldo, a 27-year-old bookkeeper from Breckenridge chose to try and cross Boreas and get to Como, on the Eastern Slope of the Rockies, and then on to Denver, where his lovely young wife waited for him.

Normally, he’d have taken the narrow-gauge train that snaked east out of town. But the tracks were buried by the Big Snow of 1899, the worst winter to hit Colorado since miners had shambled into the high country looking for gold 40 years before.

There hasn’t been a winter like it since. More than 31 feet of snow fell from December through April alone, a record never beaten. Not even close. Few people ventured into it the way Waldo did, in a light overcoat, a fedora, and 10-foot skis he could hardly use. A potent combination of love and—you gotta believe—lust drove him on as the sun went down over the Tenmile Range and the temperature dropped to 35 below zero.

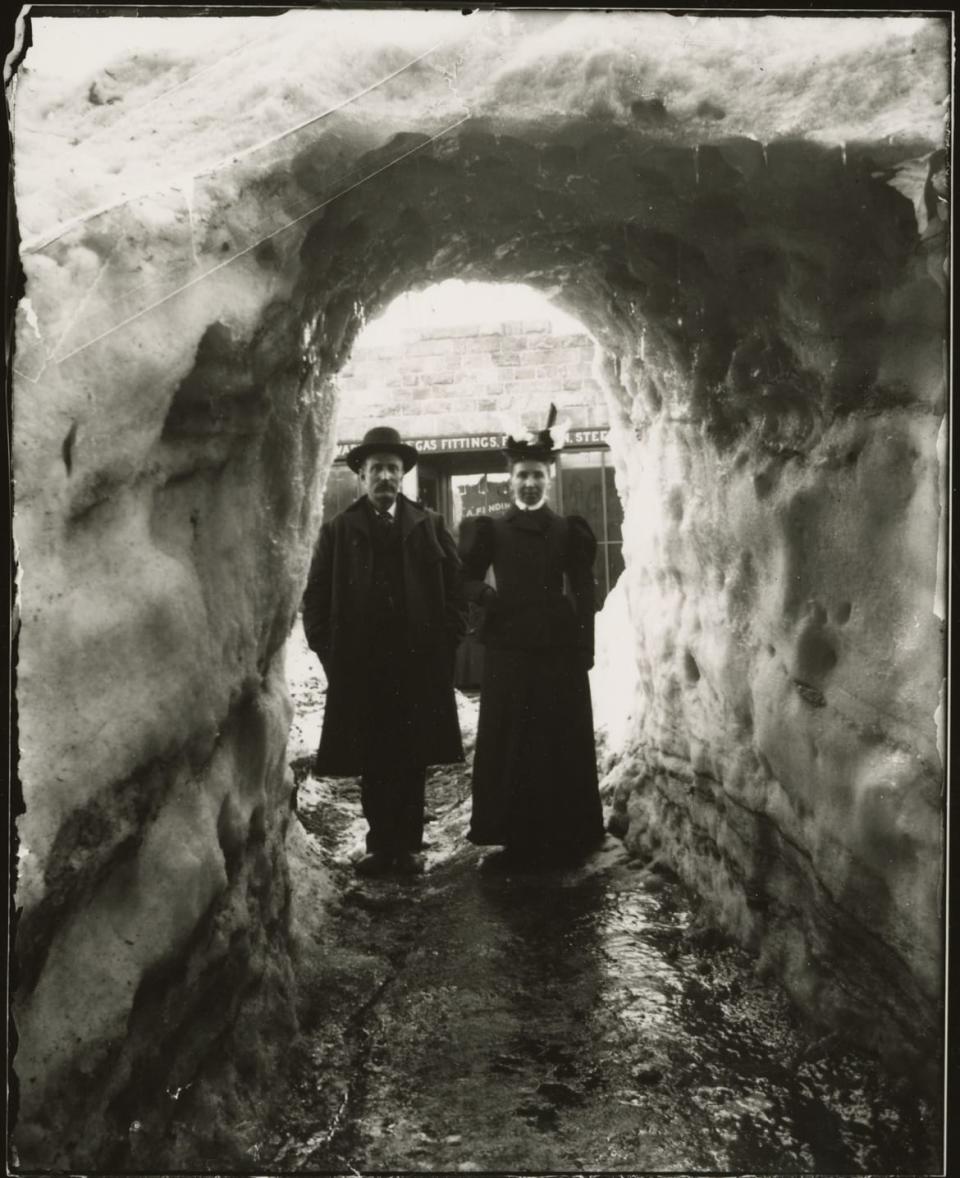

"George and Gertrude Engle stand in a snow tunnel used to access businesses on Main Street, Breckenridge (Colo.)--1898-1899" / extended description: George and Gertrude Engle stand in the entry of a snow tunnel in front of the Finding Hardware Store that leads across to the Denver Hotel, Main Street, Breckenridge, during the Big Snow of 1898-1899.

Why ski into a blizzard dressed like a businessman in Chicago? We will never know. Waldo went over the pass with two other men, both of whom had dressed for near-Arctic conditions. I think Waldo, an Illinois native, had come to rely on the luxuries of the day: trains that scaled the steepest mountain passes; wood stoves that kicked out furnace-like heat; and beds covered in quilts. Flatlanders like Waldo could arrive in mining towns without hiking a single pass, then live like city dwellers.

“Big, kind-hearted Waldo,” as the people of Breckenridge called him (he stood over six feet tall), was the victim of a climate anomaly that year. He might have made it in any other winter. But the whole country froze in 1899. There were 45 states at the time, and the mercury in every one of them fell below 0.

Temperatures in Montana plummeted to a Siberian minus 61. Storms dumped 30 inches of snow in New Jersey in a matter of days. Food shipments in Chicago stopped for three weeks. Ice floes drifted past New Orleans on the Mississippi. Sleet clung to telegraph lines in Florida, snapping them to the ground. Kids had a snowball fight on the steps of the capitol in Tallahassee.

The weather event became known as the Great Arctic Outbreak of 1899. A massive pool of Arctic air migrated south over the U.S. The culprit was the jet stream, the west-to-east air flow high in the atmosphere that—normally—pens Arctic air in the north. That winter, the jet stream dipped farther south than it had in recorded history, and frigid air followed.

These days in the American West, it’s hard to imagine the blizzards of 1899. Most every winter is warmer than the last, and the summers are often ruined by smoke from wildfires. All of that, and worse, is predicted by climate change. Surprisingly, so are Arctic outbreaks like the one in 1899 (the journal Nature described the mechanics in a study last March).

The East Coast and Midwest are expected to freeze most often. December’s deadly snow in North Carolina is evidence. So is January’s fatal Arctic outbreak in the Midwest. In March, another, bigger outbreak stretched across the country, driving temperatures down to just 9 degrees as far south as Tulsa, Oklahoma. North Platte, Nebraska, fell to a March record of minus 25.

In Colorado, it snowed like it was 1899. Breckenridge got 40 inches in three days. On March 3, an avalanche crashed down the granite walls of Tenmile Canyon. Video of the slide showed a towering plume of snow filling the canyon. Four days later, another avalanche buried four cars under 15 feet of snow near Copper Mountain Resort. Next, a “bomb cyclone” hit the Colorado plains. Winds at the Denver airport howled to a record 80 miles per hour as a Florida-worthy hurricane, but with snow, struck the middle of the country. Tornadoes tore across New Mexico. Hail the size of baseballs hammered Texas. A biblical flood swept away whole towns and herds of cattle in Nebraska and Iowa.

Unless we act fast, weather anomalies like this are going to become routine. The frigid winter of 2019 shows that the world isn’t going to end in fire, as one might expect from global warming—but maybe in ice. Given that, it might be wise to study the winter of 1899 on the roof of America and see how people coped.

Mattie Walker, a 27-year-old school teacher from Kokomo, a vanished mining town near Copper Mountain, wrote about the winter. It began, she said, just like any other.

“Large feathery flakes fell until Kokomo was a city of whiteness,” she wrote in a letter. “The wind would blow occasionally and heap the snow into great drifts, but this was nothing uncommon for this place and passed almost unnoticed.”

Then the winter got real. Snow started falling by the foot in January, and the wind blew constantly. A train left Kokomo on January 17, and one didn’t return until April 27. It wasn’t for lack of trying. Railroad operators outfitted trains with rotating blades that bored through snow like mammoth drills. But even those couldn’t dislodge the soaring drifts that walled off the tracks on the Continental Divide.

Coal ran out, and townspeople had to dig through snow to get wood off nearby hills. Telegraph lines fell, and the only mail came from Leadville, 20 miles away, by snowshoe. Fresh food disappeared. People left the table hungry, and everyone, not just the miners, played cards, a game considered too rough for women.

“I began to be haunted by the dreadful fear that the snow would continue to fall until the valley was filled,” Mattie Walker wrote, “and the people of this little camp, like the inhabitants of Pompeii, might in long years after be dug from this tomb.”

People in nearby Breckenridge paid men to ski 20 miles over Boreas Pass to Como, on the eastern side of the Divide, for supplies and mail. Bored, and tired of trudging through snow, a group of Breckenridge men tried to build a “snow bike,” with a paddle wheel on the back to push it along. It broke on the first outing and became kindling.

Dances in Breckenridge that winter often went until 4 a.m.

Elmer Peabody, 14, had to trudge through feet of snow every day to feed the family’s cow. The animal never left the barn all winter because its small pasture was buried, and that probably saved its life, Peabody wrote years later. When their neighbor went out to milk her cow, she found it butchered by a group of men desperate for food. They paid her, at least.

Loren Waldo didn’t last long, marooned in a mountain town without his pretty new wife, Minnie. She lived with her mother in Denver, while Waldo stayed in Breckenridge to watch over mining claims he had made. In 1887, two lucky diggers had pulled a 12-pound chunk of crystallized gold out of nearby Farncomb Hill, the biggest ever found in Colorado. The monster rock, called Tom’s Baby, stoked gold lust in a town that already had it bad.

Waldo had been torn between gold and his girl. Now, his claims were buried. His gold, if there was any, was safe under feet of snow, and he had little reason to stick around.

It had to feel bleak. Avalanches fell around Breckenridge, obliterating whole hamlets. One slide blocked trains near Glenwood Springs. When men came on a wrecking train to shovel out the tracks, another slide ripped down and pushed them and their rig into the river, killing three. Cabins in Swandyke, just a few miles from Breckenridge, disappeared in a slide soon after. Another one near Central City smothered a mother and her baby daughter in their cabin. Her two young sons survived. Mattie Walker wasn’t crazy: Colorado was becoming Pompeii.

Waldo saw his exit on February 10, when two men came into J.H. Hartman’s general store, where Waldo worked, looking for some tallow candles. Tallow kept snow from freezing to the bottoms of wooden skis, and the men, Eli Ruff and Ed Flanders, were fresh out of it after skiing 19 miles from Kokomo to Breckenridge. They, too, wanted to get over Boreas to Denver.

Ruff and Flanders were hardcore, especially Flanders. He worked as a fireman on the railroad, shoveling coal into engines. Before coming to Colorado, the wiry 32-year-old fought bloody battles in Cuba during the Spanish–American War. “His constitution is that of iron,” wrote a Denver Post journalist who interviewed him after the Boreas crossing.

When Waldo learned that Flanders and Ruff planned to cross Boreas Pass on skis, he pleaded to join them. He had recently purchased a pair of Norwegian shoes, which is what people called skis at the time. He hadn’t done any “extended walking” on them, he told Flanders, but he “had been practicing in the vicinity of Breckenridge with some success.”

Waldo was a big man, but even for him, his skis were abnormally long (10 feet) and absurdly heavy (made of ash). Flanders, by contrast, had a lighter 8-foot pair, and he knew how to use them. So did Ruff. To climb, they wrapped burlap sacks around them under foot, giving traction.

Flanders and Ruff stayed in Breckenridge that night. They left the next day at 11:20 a.m. after Waldo collected his pay from Hartman. Waldo’s gear must have alarmed them. He dressed for a winter walk in Denver, with a skull cap under his fedora and a pair of black mittens. He had lashed a suitcase over his shoulder. It was the 1899 equivalent of skiing in jeans.

Worse, it became clear immediately that Waldo couldn’t handle his Norwegian shoes. Instead of skiing up the railroad line, the men slogged up Indiana Gulch, a shorter route to the top of Boreas Pass. There was six feet of fresh snow, and the wind blew hard. Waldo lagged. Flanders and Ruff, sweating from the climb, froze every time they stopped to wait.

The three men took a longer rest three miles from the top of Boreas at Sutton’s mill. History doesn’t say if the place milled rock or timber, but the owner had a warm stove and plenty of coffee, and Waldo drank a lot of it. This was a certainly a blunder. Caffeine constricts blood vessels, denying blood flow to the hands and feet. It’s also a diuretic, flushing out crucial fluids along with all the sweat. Waldo may have felt better after his stop at Sutton’s mill, but it wouldn’t last.

The Section House where Waldo should have stayed, almost exactly 120 years after he left there.

“We kept together for some time, but he began again to drop behind,” Flanders told the Denver Post. Ruff warned that if they kept stopping, their sweat would freeze them to death. They waved for Waldo to follow as he struggled in the snow, but they kept moving, losing sight of him after a mile.

The old mountain railroads needed a lot of maintenance, so workers lived year-round in houses along the line and minded their section of track. These “section” houses dotted rail lines throughout the Rockies. Flanders and Ruff bypassed the tall, inviting house at the top of Boreas and skied down to a lower one, arriving at 6:30 p.m., just before dark.

Waldo, meantime, reached the top of the pass at 5:30 p.m. He warmed himself in the section house that Flanders and Ruff had skied past. Science says that Waldo should have been dead long before he reached the top of Boreas. It’s tempting to argue that love kept him going, but the Illinois native had probably acclimatized to the altitude and cold soon after he arrived in Summit County from Denver. Record snow and blistering cold had almost certainly become routine for him by the time he took off for Como, lulling him into thinking he could survive outside the safety of his house in town.

The agent at the summit section house told him to stay the night. I can tell you from experience that he absolutely should have. As it happened, we rolled into the smaller, older cabin next to the summit section house 90 minutes before Waldo did, exactly 120 years later. He would have been trudging through the snow field just to the west of us as we lit the wood stove and started water for hot cocoa.

I went out at 5:30 p.m. to see the world as Waldo did. The sun hung at the very same angle: low in the southwest and diminished. The wind tore across the ridge, blowing snow over to the Atlantic side of the Continental Divide. Clouds skittered eastward. Remove a glove for too long to take a picture, and it took an hour to warm your hand.

Waldo ignored the station agent and went back out in this frozen world, but worse. When we were there, the thermometer at the top of Boreas read 1 below zero. On Waldo’s final night, it fell to minus 35. I can’t imagine that he lasted more than a few more hours after leaving. At around 7:30 p.m., I put on my skis and headed east toward Como. The trees had turned black in the twilight. All but the tallest ones would have been buried completely in Waldo’s day, leaving a field of white.

South Park, one of Colorado’s three broad mountain basins, spread out far below me. Somewhere down there was Como. If he could see South Park, lit by a far-off sunset like it was for me, the pleasant, flat valley would have drawn Waldo onward.

I stopped, dropped my poles, and laid down on the wind-crusted snow. Within seconds, the cold penetrated all my layers. Blowing snow collected in the creases of my jacket. I could imagine freezing there and being covered in no time. At 1 below zero, with a steady wind, frostbite can start in 30 minutes. At minus 30, in can begin in just 5 minutes.

Was it madness to go? Yes, but it may not have looked that way to Waldo. In 1899, people lived all over the mountains of Summit County. Railroad agents lived in section houses at 11,500 feet. Men worked in mines and mills just below timberline. Waldo may have felt safe until the end, given the crowd.

A few days after Waldo disappeared, a Denver Post reporter visited Minnie at her mother’s house in Denver and described the scene: “Two helpless women, wrung with anxiety, sat in a cozy back room of the neat cottage at 1855 Lafayette Street this morning, as they have sat for many days, waiting for news they almost dread to receive.”

A friend arrived and tried to calm Minnie by suggesting that Waldo could be holed up in a miner’s cabin, snowed in and suffering from exposure, but very much alive. “Oh, but if he is sick, I want to be with him,” Minnie said.

Waldo’s father, Nathan, spent much of the spring looking for his son, helped by Waldo’s friends from Breckenridge. Late storms thwarted the search well into April, piling more snow on the dead man. A train arrived in Breckenridge on April 24, the first one in 79 days. In May, searchers found a pile of clothes beside a dead dog. The clothes contained theater tickets, but no money, and Waldo was known to have been carrying a wad.

In May, Waldo’s father offered a $200 reward for his son’s body, about $6,000 in today’s dollars. Finally, on June 3, a man named James Craig found Waldo, face-down in a stand of pine. He shouted to Waldo’s father, who searched nearby.

The body was black from exposure, the face weathered beyond recognition. Waldo had tried to save himself by wrapping shirts from his valise around his legs. Then, he must have given up. One glove was off, and a pencil lay beside him. His father concluded that Waldo had been writing to his wife.

“He realized that death was at hand,” his father told the Denver Post. “He pulled off one glove and got out his pencil and paper. If he wrote a note, the wind blew it away, for death came before he got the glove on again.”

Waldo was one of 105 Americans who died in the first two weeks of February 1899 alone. Avalanches killed many of them, and the cold got the rest. None of them had ever seen a winter like that, and many, like Waldo, underestimated its danger.

With the climate changing, we have to ask ourselves what dangers we’re not seeing, what catastrophes we’re laughing off. Some of us are going to find ourselves in frigid white-outs in the Rockies, watching our SUVs run out of gas after avalanches close the Interstate. Others are going to be swept away in ice-laden floods like the one this month that submerged Verdigre, Nebraska, and Hamburg, Iowa. These deaths will make headlines, until they become routine.

A tip if you’re the person in the SUV: put some candles and matches in the glove box. A single candle will heat your rig for hours while you wait for a rescue. In the meantime, try to shrink your carbon footprint. It’s your only hope.

This story was produced in partnership with Delve.