A new 'gold rush' for lithium at Salton Sea could hurt Native lands, as mining often does

They say the only people who made money during the gold rush were the people selling picks and shovels.

Folks were so focused on getting rich they stopped thinking straight. They made bad decisions. Went broke. According to the Quechan creation story, gold comes from the blood of a giant snake. It is said that digging up this gold can only bring death, so we try not to mess with it.

Yet companies like KORE mining keep trying to destroy our sacred sites at Indian Pass, in eastern Imperial County, to dig for gold. They only think about the millions and millions of dollars they can make, not about the destruction they will bring to desert ecosystems and our Native community.

Today we are facing another mining rush, except it isn’t just gold this time. It’s other metals like lithium that we need for electric cars.

A bit west of Indian Pass, new technologies for lithium extraction are being proposed near the Salton Sea on the ancestral lands of several tribes. The companies promise jobs and minimal environmental impact, but we’ve heard those promises before. We need free, prior and informed consent before any type of extraction goes ahead.

Every year millions of cars pass through the Fort Yuma Quechan Reservation while traveling between San Diego and Phoenix, a constant reminder that we aren’t moving fast enough to address climate change.

So getting away from gasoline and other fossil fuels is great, but there’s a problem. The mining laws in the United States were written before the car was even invented. It was 1872, when a prospector had one pick, one shovel, a pan, and a jackass to carry things. Mining today is industrial, with huge open pits that completely transform the land. They use chemicals like cyanide to process the ore, which creates millions of tons of toxic waste.

Current federal mining law fails to provide even basic environmental protections. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, hardrock mining is the country’s number one source of toxic pollution, responsible for polluting 40% of the headwaters of western watersheds. My biggest fear is that mining in the California desert could contaminate the aquifer we depend on for our drinking water, and even reach the Colorado River.

So before we get carried away with another gold rush, we better fix that 1872 mining law.

The Biden administration has said over and over that we must reform federal mining laws to end the toxic cycle of sickness in Indigenous communities, where we have disproportionately high rates of cancer and birth defects. A report by MSCI found that among US energy transition metals “97% of nickel, 89% of copper, 79% percent of lithium and 68% of cobalt” are located within 35 miles of Native American reservations and tribal lands.

We must learn from the past. What good is it to replace dirty oil with dirty mining? The toxic cycle will continue. Indigenous communities will continue to be sacrificed for the “greater good.”

There is a better way. Focus on getting these critical minerals in the most sustainable way possible: by recycling, reusing, and extending the life of materials and products we already have. Research shows that it can work. Europe is already going that direction.

The 1872 mining law was designed to “settle” the West, in part to evict the Indigenous peoples already living here. The companies always talk about their mining claims, but our claims are much older: the sacred sites that show our people lived here thousands and thousands of years ago.

Around the same time the mining law was passed, California had a state law that offered a bounty to gold-rush settlers for killing Native Americans. That law may be off the books, but the old mining law persists, and it’s just as dangerous. It threatens our way of life, our heritage, our land.

Four California Congressional members, Reps. Jared Huffman, Alan Lowenthal, Katie Porter and Mike Levin, have sponsored a new bill to reform the 1872 mining law. Hopefully the rest of the California delegation will declare their support as well. And earlier this year, a federal interagency working group on reforming mining regulations opened a public comment period and consultation process.

Will this protect Indian Pass and other sacred sites? We will see.

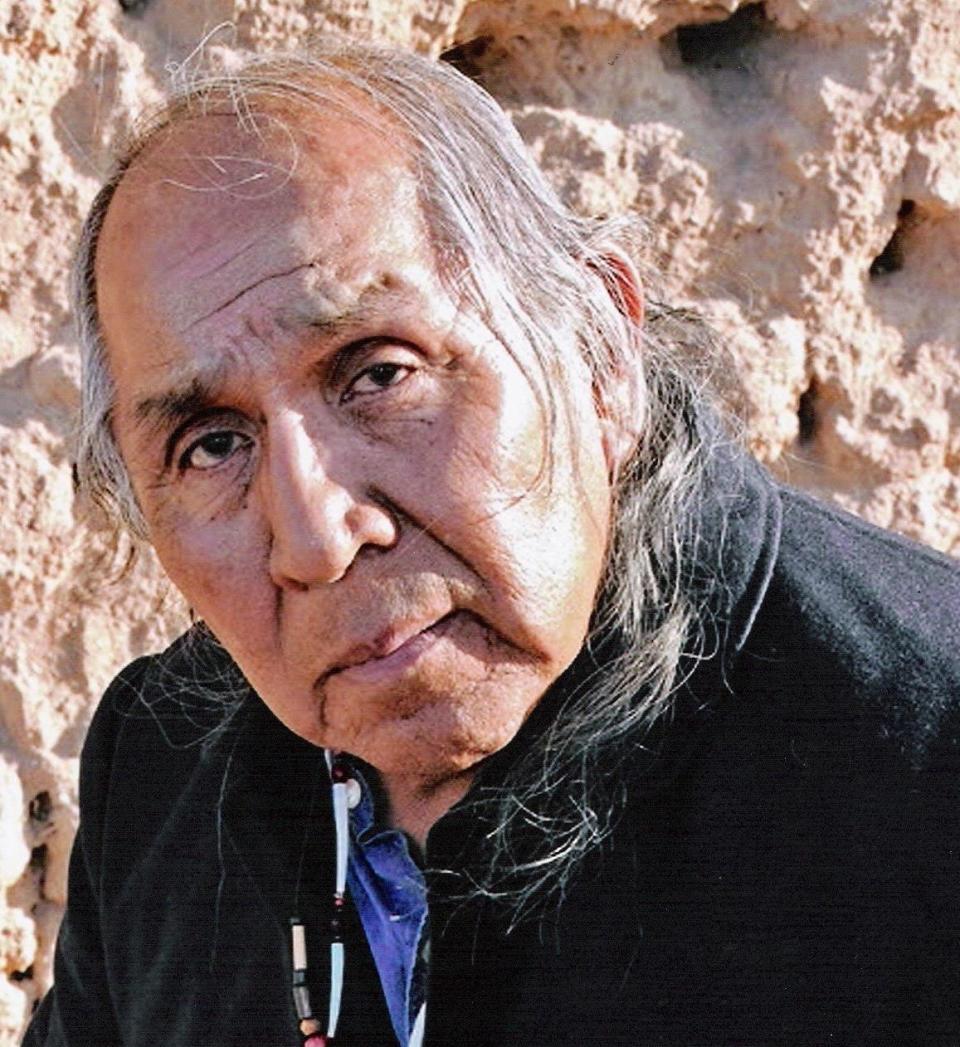

Preston J. Arrow-weed, who lives in the Fort Yuma Quechan Reservation and El Centro, is a Quechan and Kamya educator, environmentalist, actor, playwright, and singer. He is a member of the Quechan Tribe and president of the Ah-Mut Pipa Foundation.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Salton Sea lithium mining could hurt Native lands | Column