Golf forgot Tony Lema. Sixty years after his near-Masters win, it’s time we remember

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Tony Lema levitated atop the 18th green at Augusta National Golf Club. He flung his putter skyward and thrust his right arm in a fist pump, lifting his left leg off the ground.

Sunday at the Masters elicits such reactions. Canning a 25-foot birdie putt to tie Jack Nicklaus for the lead? That’s the stuff woven into the framework of traditions unlike any other.

At least it’s supposed to be.

It’s why on April 7, 1963, “Champagne Tony” glided off the well-manicured putting surface and up the hill toward the clubhouse, the hope of a green jacket in his first Masters start within reach.

“On the 15th, 16th, 17th holes, I felt like I was choking a little bit,” Lema told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution at the time. “But on the 18th, I loosened up and let it fly.”

History deifies winners. Lema won 22 times in his professional golf career. That afternoon wasn’t one of them.

Nicklaus birdied holes 13 and 16 to finish with a final-round 72, a one-shot win and the first of his record six Masters titles.

In an alternate universe, Lema would’ve been part of this week’s Champions Dinner celebrating 2022 Masters victor Scottie Scheffler. He’d share stories of his time on tour with Jack, Gary Player and Arnold Palmer ahead of this, the 87th Masters, and the 60th anniversary of his final-round duel with Nicklaus.

But there are no such remembrances here at Augusta National.

Lema played in just three more Masters tournaments, never finishing better than a tie for ninth. He died at 32 years old in 1966, when the twin-engine Beechcraft Bonanza carrying him and his wife, Betty, crashed into a pond short of the seventh green at Lansing Sportsman’s Club in Illinois.

The eccentric persona Lema displayed and his near-win at Augusta made him a star. Yet in the six decades since, he’s been relegated to a single note on Page 40 of the 2023 Masters media guide.

“60 years ago: Jack Nicklaus wins his first of six Masters after defeating Tony Lema by one stroke and Julius Boros and Sam Snead by two,” the line reads.

Golf has seemingly forgotten Tony Lema. Perhaps it’s time we remember.

The birth of ‘Champagne Tony’ and a pro golf career

Lema laid siege to golf courses nationwide in the mid-1960s. His lengthy play off the tee wowed onlookers long before specialized balls and distance control littered headlines.

His charisma, though, is what made this ex-Marine from Oakland, California a superstar.

As the legend goes, leading the 1962 Orange County Open Invitational after three rounds, Lema poked his head into the media tent, sipping on a beer. “If I win tomorrow, it’ll be champagne,” he said of his post-round drink of choice.

San Francisco golf writer Nelson Cullenward slyly retorted, “If you win, you’re going to buy champagne for all.”

Lema won the tournament in a three-hole playoff. He sent the media contingent bubbly post-round in honor of his win. “Champagne Tony” was born.

“I like to think we don’t forget our past. I like to think history is today,” PGA historian emeritus Bob Denney told The State. “... Tony was, I just think, a man who wasn’t afraid to take a risk.”

Every Lema story oozes more charisma than the last. The April 13, 1963 edition of the Chicago Tribune recounts a night in St. Paul, Minnesota in which Lema entertained party guests on the 12th floor of a local hotel. With a little hooch-inspired confidence and his natural talent, Lema hit golf balls through the window and onto the street.

Need more? How about Lema’s first-ever professional win, chronicled in a 1963 Sports Illustrated profile on the smooth-swinging Californian:

“Even before he came out on the tour as a regular in 1958, Lema had won one worthwhile event, the 1957 Imperial Valley Open. It was there that he had assumed he was out of contention and cheered himself up at the bar — three times — only to be summoned out for a sudden-death playoff against long-hitting Paul Harney. The surprised Lema, feeling the pressure but apparently no pain, won on the second hole.”

“Tony was a pretty good boy, but he liked to party and stuff like that,” quipped the late Jim Ferree, a close friend of Lema’s during his playing days who spoke to The State shortly before his death on March 18. He was 91.

The rise to PGA Tour stardom

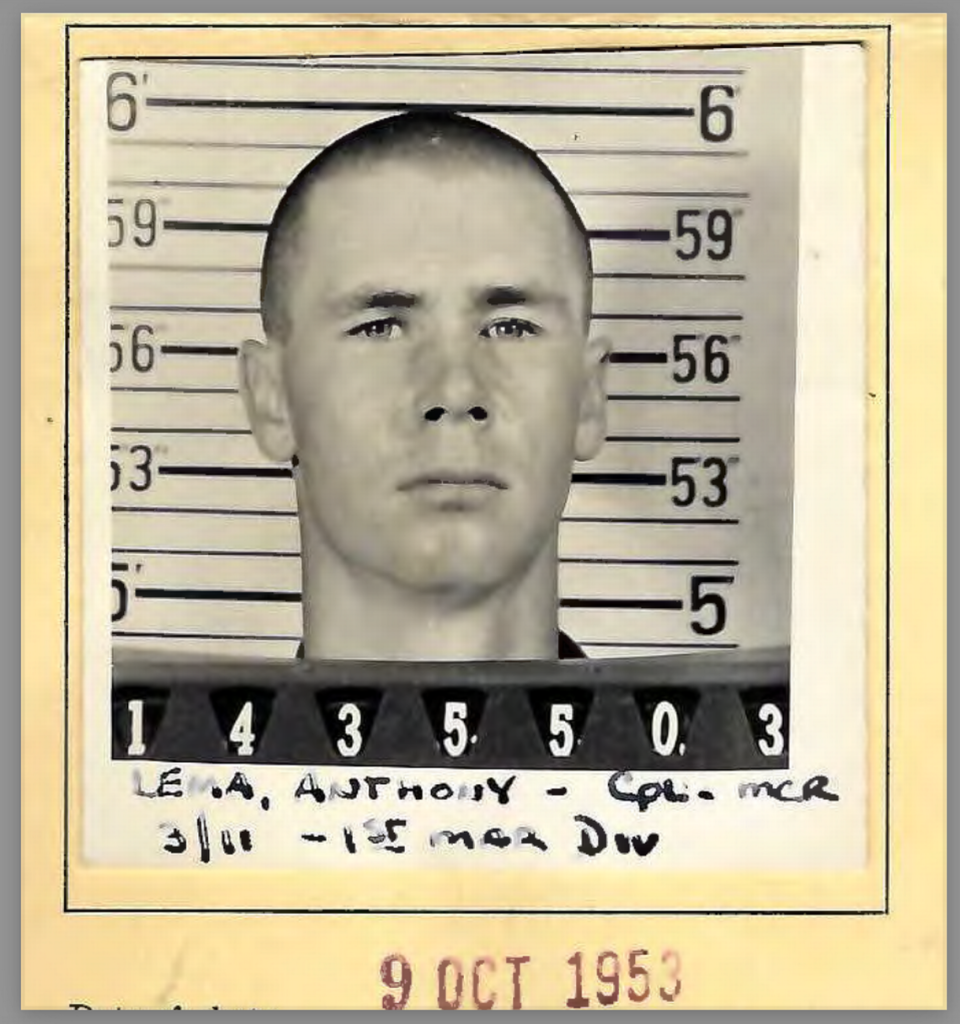

Lema’s climb toward PGA Tour superstardom was a slow burn. He learned the game as a child at Oakland’s Lake Chabot Municipal Golf Club, but enlisted in the Marine Corps at 17 years old.

Lema spent five years in the Marines at the tail end of the Korean War, reaching the rank of corporal and earning the Korean Service Medal. Once back in the states, he landed work as an assistant golf pro at San Francisco Golf Club. His playing career followed shortly after.

“I hustled the assistant pros around San Francisco pretty well,” Lema told Sports Illustrated in 1963. “I’m afraid I fleeced them. I always seemed to offer them one stroke less handicap than they needed.”

Eddie Lowery, a wealthy local businessman, took notice of Lema’s talent.

Lowery’s own story is ironed into the annals of golf history. At 10 years old, he caddied for 1913 U.S. Open champion Francis Ouimet. He later made millions as an entrepreneur, backing amateur golfers in his spare time.

Lema and Lowery worked out a deal in which the Lema was paid $200 per week in expenses that would eventually be repaid, according to Sports Illustrated. Lowery also received one-third of Lema’s winnings and all debts at the end of the year would be carried forward.

“Tony was a tough kid,” John Brodie, the ex-San Francisco 49ers quarterback and an early playing partner of Lema’s in the Bay area, told Sports Illustrated in 1995. “You had to be, growing up in Oakland. We didn’t exactly lead a country club life. In fact, we were hustlers. But Tony was always a romantic. He loved good people and couldn’t stand jerks.”

Lema labored through those early days. The 1957 Imperial Valley Open was his only win in his first five years on tour. The confidence he displayed publicly was shrouded in concern behind closed doors.

Rooming with Gary Player at Doral in Florida during his short time on tour, Lema confided in the nine-time major winner that he was considering leaving golf. He figured he could be more productive doing odd jobs back home in California. “Gary, I don’t know how long I can keep going,” Lema said.

Player insisted he stick it out. Lema relented. Success followed.

“It was like God put his hand on him and said, ‘Now, my son, you’re gonna go forward,’ ” Player told The State. “From the man I heard say, ‘I don’t know how long I can go on for,’ and then to what he achieved in his short career is admirable.”

The Masters and — finally — a major win

Only once since the Masters’ second tournament in 1935 has a player won in their first go at Augusta National — Fuzzy Zoeller (1979). But the man with a booze-infused moniker and a Sports Illustrated cover on the horizon had his name floated as a perceived contender in 1963.

Lema entered that Masters having found his form. He’d won three of the final 10 events the season before. The footing he desperately sought was there. That attracted its share of attention.

“I realize no first-timer has ever won here before,” Arnold Palmer told the Macon News ahead of the 1963 Masters. “But that does not mean it can’t happen. And if it does happen, Lema could be the boy to do it. Have you seen some of his drives? He hits ‘em clear out of sight.”

Lema picked the brain of two-time runner-up Ken Venturi, who was edged out by Palmer at the 1959 and 1960 Masters. Lema hoped it would help familiarize himself with the grounds. Augusta, after all, rewards those who have spent years toiling on its tricky and twisting greens.

Ever the confident one, Lema later told reporters he felt on Thursday he could win the tournament. That was before shooting 74-69-74 over his first three rounds.

Lema entered Sunday 1-over, three-shots off Nicklaus’ pace and needing an electric display to have a chance. Champagne Tony delivered.

The one-time Marine’s ball-striking was spot-on, hitting 16 of Augusta’s greens during his round. His triumphant birdie on 18 capped off a 35-35—70 for a 2-under round. Lema entered the clubhouse, washed his hands and waited.

Nicklaus still prowled the grounds.

The Golden Bear closed his day with those back-nine birdies. A 3-foot par on the 18th gave Nicklaus his second major title and his first green jacket. Lema settled for second.

Post-round, Lema claimed he wasn’t deserving of a Masters title in his first go. Anyone who saw him play begged to differ.

“Tony Lema could become one of the best golfers on the circuit,” Frank Veholm of the Columbia Record wrote. “He should have nothing else to prove to himself that he hasn’t already proven.”

The form Lema flashed at Augusta National during his 1963 debut snowballed. He owned eight top-10s in majors between 1962 and 1966 — including his lone major title at the 1964 Open Championship.

That win, like anything involving Lema, is a story in itself.

Six weeks before Lema’s title at St. Andrews in Scotland, Palmer loaned him a Tommy Armour putter at the Cleveland Open. Mistake made.

Lema conjured a kind of juju in the club. Perhaps there was some kind of winning wizardry contained within its shaft. After all, it belonged to Palmer — a seven-time major winner and pioneer of the modern game.

In Cleveland, Lema holed putts of 40 and 45 feet during the final round. Palmer matched Lema’s 54-hole score to force a playoff, only to be defeated when Lema birdied the first extra hole to take home the $20,000 winner’s check.

Then Lema won again. And again. And again.

He won four times in six weeks, his final title coming at St. Andrews. The runner-up? Nicklaus — who finished a distant five shots back.

“Arnie didn’t know he was giving the guy a magic wand,” wrote Atlanta Journal-Constitution columnist Jesse Outlar in July 1964. “But he found out the hard way.”

‘Here was a star in the making’

Jim Ferree flipped channels in his Florida hotel room on July 24, 1966. His long flight from the PGA Championship at Firestone Country Club in Akron, Ohio to Florida called for a few minutes of pause.

Ferree tuned the television to the “Ed Sullivan Show,” providing background noise as he eased into his digs. That only lasted so long.

“(Sullivan) said, ‘I’ve got bad news for everybody: Tony Lema has been killed,’ ” recounted Ferree, his voice growing somber.

Lema was hours removed from his final round at the PGA Championship, where he finished T-34 and 15 strokes behind winner Al Geiberger. He’d chartered a plane to fly him and his wife, Betty, who was carrying the couples’ first child together, to Chicago ahead of a tee time the next day.

The plane never arrived, crashing a half-mile from its destination. Tony, Betty and both pilots were killed in the wreck.

“I cried,” Player said. “… I felt so sad because here was a star in the making.”

Legacies are a fickle thing. Time erodes the accomplishments of even the most famous.

Player, now an introspective 87 years old, concedes he’s thought about his own legacy as he’s aged. One hundred and fifty-nine professional wins. Nine major titles. Three green jackets.

“So what?” Player said. “It’s only a matter of time before everybody will say, ‘Who was Gary Player?’ ”

We barely got to know who Tony Lema was.

Outside of his dominating win at the 1964 Open Championship, a victory that forever etched his name on the Claret Jug, Lema’s legacy remains one of what-ifs and potential never fully realized.

On Thursday, Nicklaus and Player will be among the three honorary starters that kick off the 2023 Masters. In that aforementioned alternate universe, Lema might be there, too.

One shot better, and, perhaps, we’d still remember Tony Lema.