Golf, handshakes and a Mar-a-Lago conga line: Squandered week highlights Trump’s lack of COVID-19 focus

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Corrections & clarifications: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Florida Sen. Rick Scott was at Mar-a-Lago on the weekend in question.

By Friday, March 6, there was no escaping the fact that the spread of the novel coronavirus would soon upend American life.

There were confirmed cases in two dozen states, including Washington, where a state of emergency had been declared after at least 10 people died in the previous week in connection with a single nursing home. New York City was experiencing an alarming upward trend in cases. A cruise ship carrying infected passengers idled off the California coast, waiting for a port to allow them to disembark. Hospitals, nursing homes and health officials around the country worried over a lack of testing capabilities and a shortage of medical equipment.

The annual music festival South by Southwest was canceled that day, joining an array of scuttled movie releases and concert tours. The Dow plunged nearly 1,000 points. And just a day earlier, the chief of the World Health Organization (WHO) had explicitly beseeched world leaders to prepare, warning that the “epidemic can be pushed back, but only with a collective, coordinated and comprehensive approach that engages the entire machinery of government."

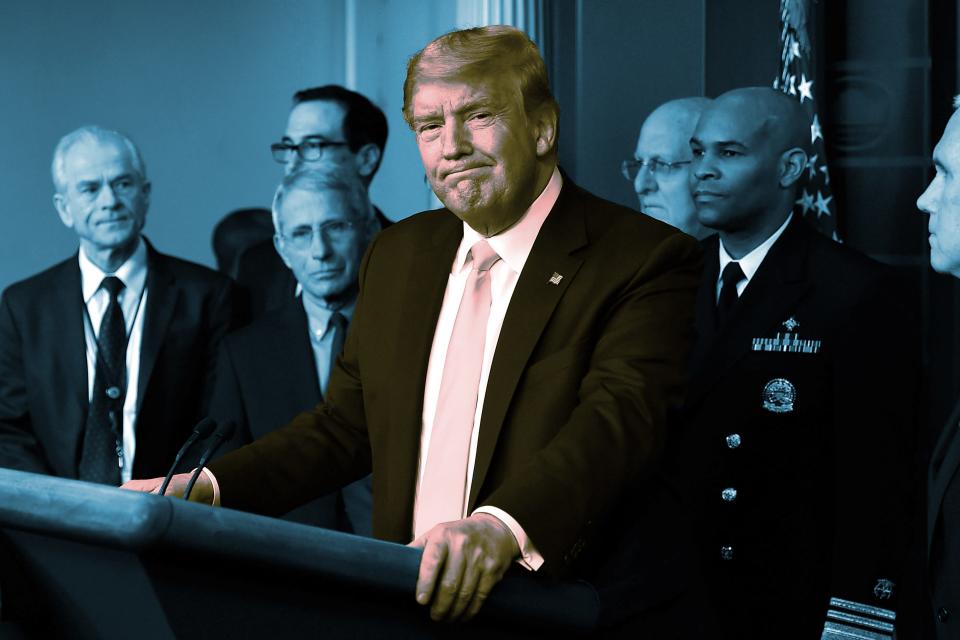

Armed with all of that evidence, President Donald Trump spent the next week treating COVID-19 in much the same way that he had over the previous two months: he hosted large gatherings at Mar-a-Lago, went golfing, attended fundraisers, dispensed misinformation about the virus and flouted social distancing guidelines known to stem its spread. If his behavior was meant to be a model for Americans to follow, the message was clear — life could proceed as normal.

Trump and his closest supporters now insist that he always understood the threat COVID-19 posed to the U.S., despite his repeated assurances that it was under control and less harmful than the flu. But perhaps the clearest indication of Trump’s dismissal of the threat the virus posed is an examination of how he spent the week leading up to Friday March 13, when he declared that the virus constituted a national emergency.

That declaration, issued a month ago this week, prompted a cascade of measures by governors and other officials that have essentially halted public life in the U.S. in a frantic effort to limit COVID-19’s spread. Although disruptive, those measures have been credited with limiting new COVID-19 outbreaks in places that had not yet become a hot spot while helping to tamp down the exponential rise in cases in cities like New York, where a crush of sick patients have overwhelmed hospitals.

USA TODAY interviewed half a dozen experts in epidemiology, economics and the medical supply chain who said Trump squandered an opportunity that week, as he had for months, to take significant steps that would have saved lives and put the country in a better position to fight the virus.

“The United States is one of the richest countries the world has ever seen,” said Heather Boushey, head of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a nonprofit economic research and grantmaking organization. “It has enormous resources. But it needs good management to marshal those resources. What we’ve got is six-year-olds playing soccer. There’s no strategy, no plan.”

The experts said it’s obvious that the U.S. would be best equipped to manage the impact of COVID-19 if the efforts to secure equipment, increase testing and shore up the economy had begun back in January, when Trump was reportedly already receiving warnings from intelligence officials and key advisors that the virus would inevitably spread through the country. And they contended that in the last month, Trump's response remains disorganized and lacking.

But they said that taking significant action during that one week before he declared a national emergency would have made a measurable difference.

“In an emergency, every day matters,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “Every week matters.”

White House spokesperson Judd Deere, in a statement, called this story "another shameful attempt by the fake news to distort the President’s record to confront this global pandemic, including during March 6-13, which was filled with action after action to slow the spread of virus, expand testing, and provide much-needed relief for Americans impacted by the outbreak."

The White House provided a recounting of the actions Trump did take in the week before he declared an emergency, from securing $8 billion in healthcare funding related to the virus, to issuing an Oval Office address to the nation, to suspending some travel from Europe. Trump has also touted his decision in January to bar some foreign nationals who had recently visited China from entering the U.S.

The White House’s account of Trump's week omitted three of the days, including a Sunday and Monday he spent in Florida hosting a birthday party for his son’s girlfriend, golfing with Major League baseball players and headlining separate reelection fundraisers at Mar-a-Lago and a donor’s private mansion.

Deere responded to questions about those activities with a question of his own: "You don't think he does work while in Palm Beach?"

Shaking hands down the Eastern Seaboard

The virus’s devastating potential had been on display for months in China, where it had brought the country to a standstill, and in Italy, where an uptick of its lethal spread was considered a harbinger of America’s near future.

Trump started his workday on Friday, March 6 with a reality check that COVID-19 was going to be more expensive than he anticipated. That morning in the Diplomatic Room, wearing his situation outfit of khakis, a white dress shirt and a windbreaker jacket bearing the presidential seal, he signed a bill authorizing $8.3 billion for healthcare and vaccine research. Trump remarked that he had only asked for $2.5 billion.

“Came out of nowhere,” Trump mused of the novel coronavirus as he held up the signed bill for the clicking and flashing cameras, “but we’re taking care of it.”

Trump then tossed the pen to a Reuters reporter — "Here Steve, this is for you after covering me so well” — and moved on to more familiar matters. He suggested that Joe Biden wants to get rid of guns and called Sen. Elizabeth Warren a “very mean person.”

Then Trump left for Air Force One and several stops as he moved southward. The journey, and the rest of his week, was a highlight reel of how to ignore the social distancing guidelines the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had first mentioned in late February.

His first stop was a tornado-ravaged Tennessee, where he shook hands with his greeters who met him at the tarmac, including Gov. Bill Lee. At nearby Cookeville, he crowded in with residents near their flattened homes, shaking hands and patting shoulders. At a nearby church, roughly a hundred residents — ranging from children to the elderly — squeezed shoulder-to-shoulder and craned over a folding table to shake Trump’s hand. One man climbed over the table for a selfie with Trump.

When a reporter asked whether a fear of his supporters infecting each other with the virus might cause him to end the political rallies that have become his trademark, Trump replied, "It doesn't bother them and it doesn't bother me.”

He then headed to Atlanta for a visit to the CDC. On the tarmac, another group of officials waited to shake hands. They included Georgia’s Gov. Brian Kemp and Rep. Doug Collins, the latter who would later self-quarantine after learning he had been in contact with somebody infected with coronavirus at the Conservative Political Action Conference the previous week.

Trump’s visit to the CDC had nearly been canceled over fears that an employee there had COVID-19. Trump took the opportunity to insist to reporters at the CDC facility that the country’s virus testing capabilities could meet the demand.

“Anybody that wants a test can get a test,” Trump said. That false statement contradicted Vice President Mike Pence, who had acknowledged a day earlier that the country did not have enough tests.

‘The Trump Train’ at Mar-a-Lago

Trump’s final stop that day was Mar-a-Lago in Florida, where he would spend the next three nights. That Saturday, he spent six hours at the Trump International Golf Club, a ten-minute motorcade-ride away. Then it was back to the “Winter White House,” the site that weekend of an estimated $10 million in fundraisers and the birthday shindig for Donald Trump Jr.’s girlfriend — former Fox News personality Kimberly Guilfoyle. The president’s closest confidantes and some of the most powerful figures in the nation — including Vice President Pence, Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani and Sen. Lindsey Graham — gathered together under ballroom chandeliers and over gold-rimmed dinner plates. An Instagram video showed Trump helping to croon “Happy Birthday” to Guilfoyle, prompting her to yell: “Four more years!”

Fox News host Tucker Carlson later said that he drove to Mar-a-Lago that Saturday night and urged Trump to take the novel coronavirus more seriously. But the glitzy backdrop and a ballroom of attendees forming a conga line — or as it’s called in Mar-a-Lago, “The Trump Train” — seemed removed from the reality that a deadly, ultra-contagious virus was quietly seeping through the country.

The festivities came with a unique hangover: a series of self-quarantines. Brazil President Jair Bolsonaro had joined Trump, his daughter Ivanka and son-in-law Jared Kushner for a “working dinner” at Mar-a-Lago, and afterwards two of Bolsonaro’s aides tested positive for the virus. Republican National Committee chairwoman Ronna McDaniel and Rep. Matt Gaetz, who were at Mar-a-Lago, went into self-quarantine after learning they interacted with people who had been infected. Sen. Rick Scott also self-quarantined due to his own meeting with the Brazilian aides.

The president returned to his golf club on Sunday, this time hitting the links with several Washington Nationals players, one of whom — pitcher Patrick Corbin — posted to Instagram a photo of the president giving the thumbs-up while they all squeezed together for a group shot.

Like roughly 10 million other Americans, those baseball players soon found themselves out of work due to the novel coronavirus. Four days later, the baseball season was postponed indefinitely.

Trump got to the club early that day, and left by noon so he could attend a fundraiser brunch with nearly 900 people at Mar-a-Lago.

The next morning, Monday, Wall Street trading was halted within minutes of the market opening in an automatic emergency measure after the S&P 500 — an index of the largest corporations in the country — plunged 7%, in large part due to COVID-19 fears.

At the time of the halt, Trump was readying to leave Mar-a-Lago for the Orlando area, where he had another fundraiser planned. He spent two hours at an air conditioning magnate’s 17,000 square foot mansion, where groups of supporters in the neighborhood pressed together to greet the arriving motorcade.

At the house, Trump reportedly delivered remarks at a closed-to-press luncheon, posed for photos with supporters, and participated in a “roundtable” with donors who gave his campaign $100,000. His campaign estimated the stop raised $4 million.

Trump had been scheduled to deliver the keynote address at the HIMSS Global Heath Conference at the nearby Orange County Convention Center following the fundraiser luncheon, but the conference was canceled due to COVID-19. So instead he arrived back at the White House lawn from Florida at around 3:20 pm, forty minutes before the end of one of the worst days in Wall Street history.

In the three days he had been gone, the number of confirmed cases of coronavirus in the country had more than doubled, from 262 to 583, according to data maintained by Johns Hopkins University.

Those numbers rose exponentially over the rest of a workweek during which Trump’s White House continued to stare down the concept of social distancing. At one point, then-White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham reprimanded journalists who had reported that staffers were practicing its tenets.

“Reports that the White House has issued formal guidelines to staff instructing them to limit in-person interactions and meetings are completely false,” Grisham said in a statement forwarded to the press. “While we have asked all Americans to exercise common-sense hygiene measures, we are conducting business as usual. I want to remind the media once again to be responsible with all reporting.”

‘A tremendous amount has been learned’

On that Tuesday, March 10, Trump awarded the Medal of Freedom to retired four-star Gen. Jack Keane. For the ceremony, the White House’s large East Room was tightly packed with seated audience members, including Sen. Graham, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Attorney General Bill Barr.

Trump, 73, gently draped the medal around the neck of Keane, 77, rubbed the retired general’s shoulders and then clasped his hands. The president then worked his way around the crowded room, hand out for shaking.

By Friday, March 13, the United States was in a far more dire position than it had been the Friday before. Confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the country had topped 2,000. Thirty-seven people in Washington state had died, and New York had more than 400 confirmed cases. That Thursday, Wall Street had suffered another historic rout, dropping 10% in the worst day of trading since 1987. All sports leagues were shut down in order to stem the spread. Several states and locales had suspended school.

That day, Trump announced in the Rose Garden that he was declaring a national state of emergency.

“This will pass through, and we're going to be even stronger for it,” Trump said. “We've learned a lot. A tremendous amount has been learned.”

The Rose Garden was packed with reporters and the podium featured eighteen people squeezed together, including roughly a dozen heads of healthcare corporations.

Trump shook each person’s hand after they spoke. Finally, Bruce Greenstein, executive of LHC Group, offered to bump elbows with Trump, who had again outstretched his hand.

Trump looked amused. “I like that,” he said. “That’s good.”

Then he adjusted the microphone to his mouth.

COVID-19 missteps in microcosm

The experts interviewed by USA TODAY described Trump’s actions, and lack of them, during the week leading up to his emergency declaration as a microcosm of his administration’s failures in confronting the novel coronavirus dating back to January, and in some ways continuing today.

“The president did not realize the magnitude of the emergency and he absolutely should have,” said Tara O’Toole, former Under Secretary for Science and Technology at the Department of Homeland Security. “His failure to trust experts or the insufficiency of experts to get in his ear caused him to move at the wrong pace and scale.”

By the second week in March, the country had already fumbled its best opportunity to minimize the numbers of deaths and the length of economic shutdown through widespread testing, said Scott Becker, chief executive of the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

In South Korea, health officials had by late January tasked private medical companies with developing a COVID-19 test and by the end of February given two companies approval to begin manufacturing kits. Drive-through testing facilities were in operation before the country’s outbreak was able to gain ground, allowing officials to quarantine those who had tested positive and trace their contacts.

But in the U.S., as USA TODAY previously reported, the CDC botched its own attempts at early testing and misled state laboratories about it. As a result, even today the country continues to scramble to make tests widely available.

Though Becker said it was impossible to know how many lives could have been saved by initiating social distancing measures even a week sooner, statistics showing South Korea and the U.S.’s infection and mortality data in similar early stages of their novel coronavirus cycles revealed the dramatic effect that early isolation could have.

On February 20, 104 South Koreans had tested positive for the virus, according to the WHO. Thirty-two days later, that number was 8,961, and 111 had died.

A similar number of Americans were confirmed to have been infected by mid-day on March 6, according to the same data. Thirty-two days later, on April 7, the WHO stated that 333,811 Americans were infected and nearly 10,000 were dead.

“If we had shut the country down sooner, if we had determined the hot spots sooner and clamped down the hot spots sooner, we might not be seeing the explosive growth we’re now seeing,” said Becker.

A failure to take such steps, informed by science and following the leads of countries that were successful in batting down the virus, spoke to a more fundamental dearth of American leadership during the crisis, said O’Toole.

She said that Trump should have appointed an apolitical leader with the leeway to make strategic decisions quickly without having to first gauge their partisan popularity, in the style of Gen. George C. Marshall, who spearheaded American post-World War II recovery efforts.

O’Toole and others envisioned such a figure overseeing a cohesive command center gathering some of the country’s greatest minds to reach solutions to the biomedical, supply chain, logistical and economic challenges ahead.

Trump’s insistence on placing himself front-and-center at press briefings as the face of the government’s response to COVID-19, and seemingly disregarding expert advice as to how to handle it, instead muddied governmental messaging concerning the virus in a way that divided the country along partisan lines.

“We have not as a country or a government built a command structure,” O’Toole said. “That’s what we should have done in March.”

Dr. Joshua M. Sharfstein, professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that week before the country halted represented a lack of focus on Trump’s part to take vital steps to save lives we are losing now.

Sharfstein said that Trump could have exercised his presidential power to order private manufacturers to produce much-needed medical supplies, including personal protective equipment (PPE) like masks for nurses and doctors, a step he has continued to resist in the face of opposition from private business interests.

And rather than partying in Florida himself, he could have urged governors to close beaches before swarms of revelers arrived the next week.

“We should have had the government take over the supply chain for ventilators and PPE,” Sharfstein said. “That still hasn’t happened. We should have canceled spring break. Now those people have spread the virus all over the country and obviously made things worse.”

USA TODAY reporter Brett Murphy contributed.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Instead of prepping for coronavirus, Trump partied, golfed, held fundraisers