‘Be a good boy’ and vote for suffrage: How a mother’s note carried the 19th Amendment

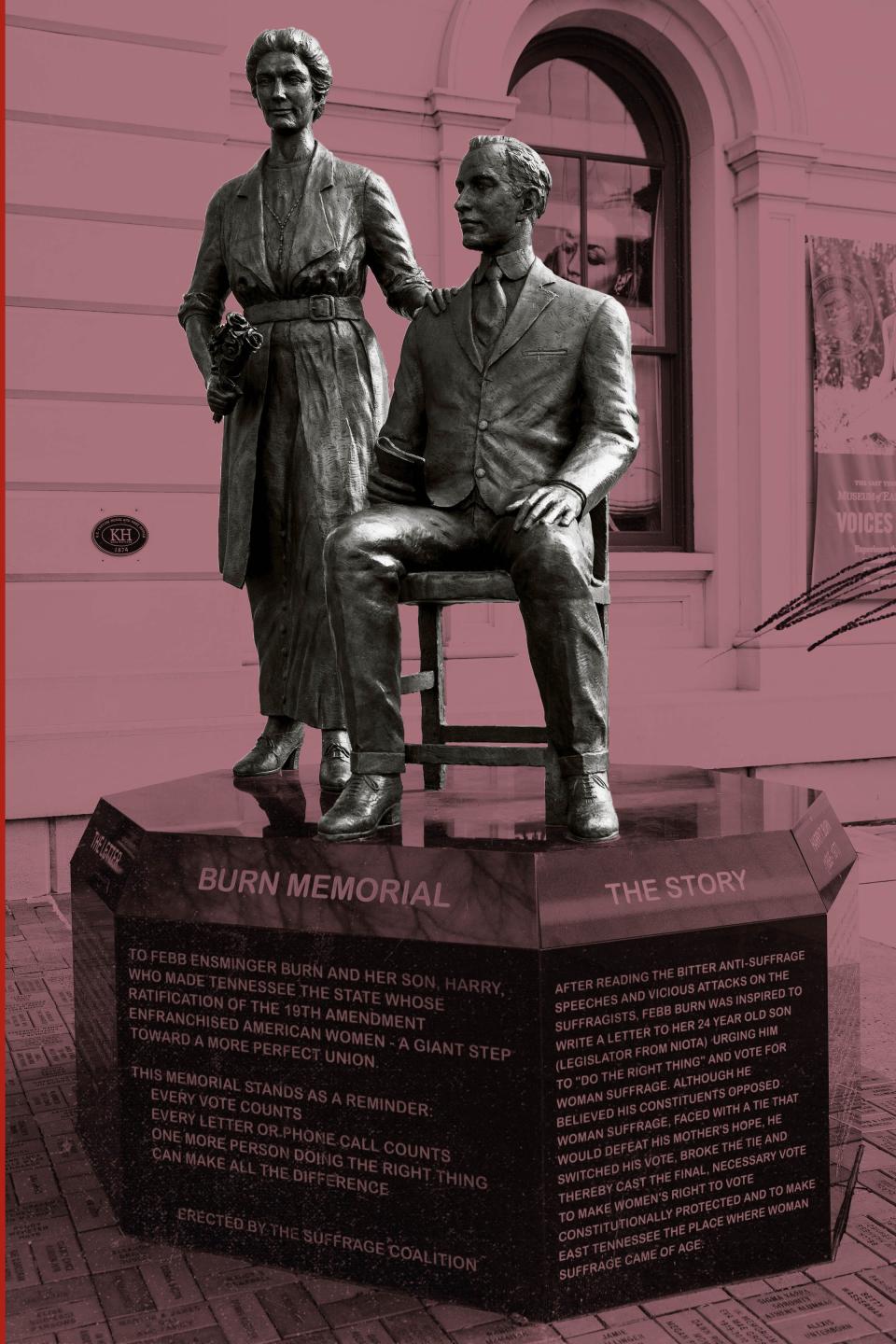

In downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, at the corner of Clinch Avenue and Market Street, stands a formal-looking statue of Harry Burn and his mother, Febb Ensminger Burn.

The mother and son statue doesn't tell much at a glance. But it commemorates a simple act between family members that changed the course of American history.

In 1920, Harry Burn, a young state representative from McMinn County, cast Tennessee's deciding vote to ratify the U.S. Constitution's 19th Amendment. The Volunteer State became the 36th to ratify — making the 19th Amendment law and securing for women their right to vote nationwide.

Before the vote, the freshman representative from rural McMinn County was undecided. But when it came time for the roll call, Burn voted in favor of suffrage.

What helped persuade him? A handwritten letter from his mother, now a piece of history preserved in a museum just one block away from the statue in downtown Knoxville.

‘Vote for Suffrage’

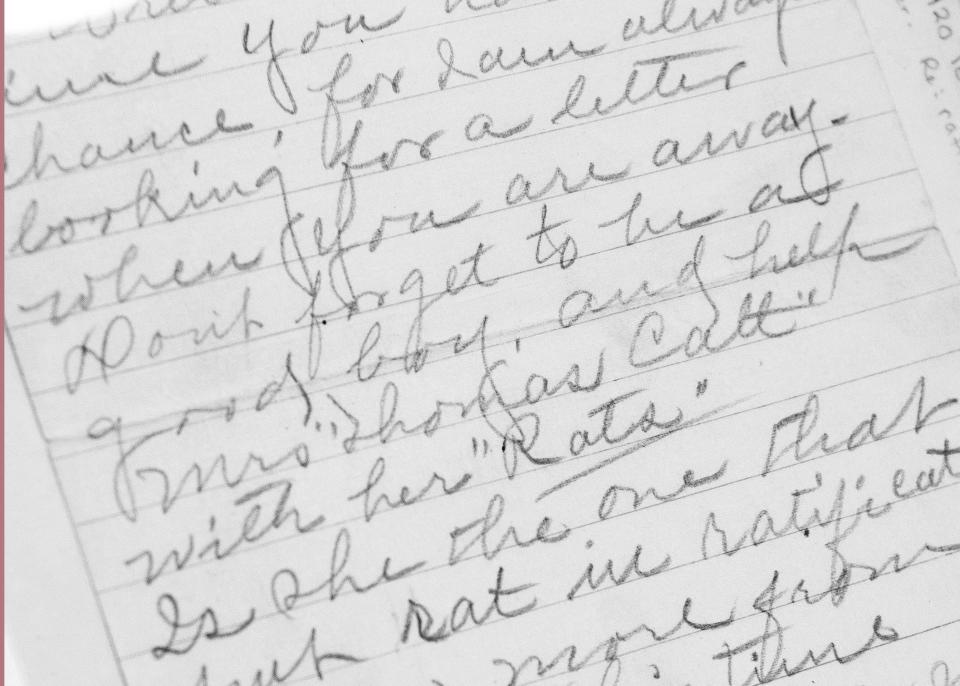

The seven-page letter is written in pencil on lined paper. The outer envelope is addressed in pen to Hon. H. T. Burn at the state Capitol building in Nashville, with a red 2-cent postage stamp in the top right corner.

"Dear Son," the letter starts. "I wish you were home too. We have had nothing but rain since you left."

Febb, 47 years old at the time the letter was written, goes on to talk about recent visitors and ask if Harry, 24, will be home for Labor Day. The letter reminded Harry to "be a good boy."

Between updates about their neighbors and Harry's siblings, she urged him to vote for suffrage.

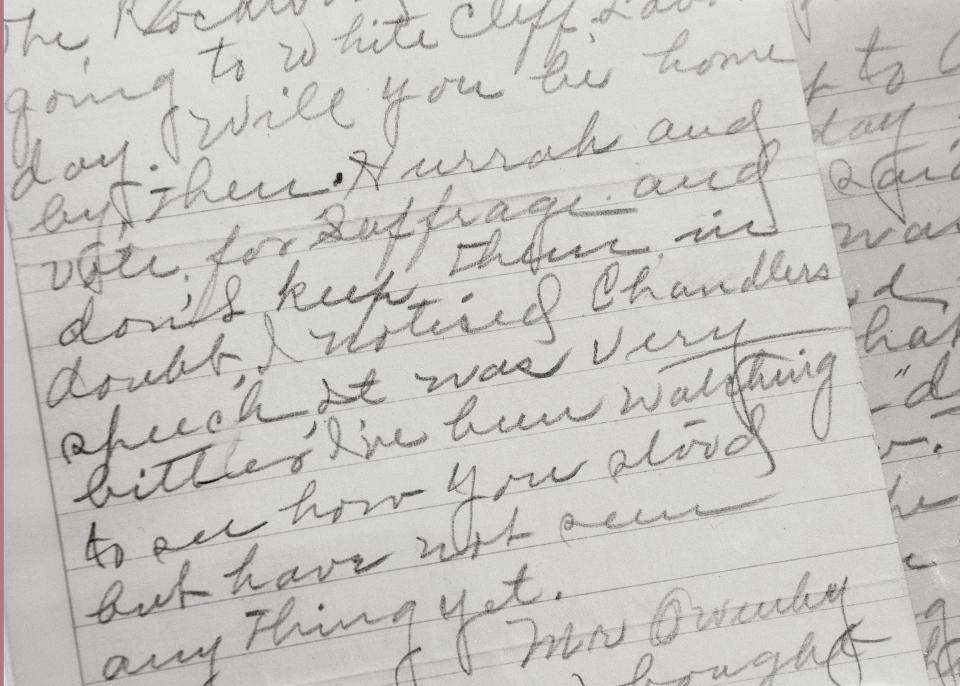

"Hurrah and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt," she wrote.

Febb "was just a fearless person," said Tyler L. Boyd, her great-great-grandson. Boyd recently published a biography titled "Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn."

"She was just a good, old-fashioned Southern woman, matriarch, who happened to get put in the middle of history," Boyd said.

Febb was educated and became a teacher before returning to work on the Burn family farm. After her husband died in 1916, the ownership of the farm passed on to her sons. Febb ran the farm, despite the fact that she could not legally own it.

Boyd said he thinks that was one spark that pushed her to advocate for suffrage.

"She really spoke about the morality of the vote ... 'I’m glad that my son believes in my rights as a mother and as a woman,' " Boyd said.

In the letter, Febb noted that while other representatives had made their position on suffrage known, she was still waiting to see how her son planned to vote.

"Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Thomas Catt with her 'Rats,' " she wrote. "Is she the one that put rat in ratification, ha! No more from mama this time. With lots of love, Mama."

Mrs. Thomas Catt was Carrie Chapman Catt, who took over leadership of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from Susan B. Anthony. Her "rats" were the people who wanted to ratify the 19th Amendment.

When it became clear that Tennessee could become the deciding state, Catt spent the summer of 1920 making speeches and advocating for suffrage across the state.

Where is the letter now?

Harry T. Burn Jr. wrote that his grandmother, Febb, "thought all adults regardless of station in life or any other characteristics had something to contribute to our political process. ... She was a very practical person."

The letter was delivered to Harry Burn at the state Capitol, where he had arrived wearing a red rose, signaling he would vote against suffrage.

After two votes to table the resolution tied 48-48, Speaker Seth Walker called for a vote on the merits of the resolution. If the amendment failed in Tennessee, finding another state to ratify it would have been difficult, Boyd wrote in his book.

Burn, the fourth to vote, quickly voted "Aye," a change that sent shock waves through the room. After the full vote was taken, shock turned into chaos.

"It was pandemonium," Boyd wrote. "There is no better word to describe the House chamber after the vote. Like a room full of graduates tossing their caps into the air upon commencement, the suffragists in the gallery tossed their yellow roses in the air. They screamed, sang and danced in joy."

The original letter is stored in the East Tennessee History Center, part of the McClung Historical Collection in Knoxville.

Steve Cotham, the manager of the collection, said the family was at first hesitant to have the letter displayed publicly because of how informal it was.

"The family story is because (Febb) was embarrassed about the letter because it was a personal letter, written in pencil on a tablet," Cotham said. "She was a very well-educated woman and if she was going to make a plea, for something formal, she wouldn’t have done it that way."

The vote for suffrage "was a hard battle" in Tennessee, Cotham said. Once it passed, some legislators immediately moved to try to undo the vote.

"It was a real crucial moment because once the procedures in the vote had happened, the legislators were trying to undo it," Cotham said. "But once it happened, the official documents went to the Tennessee secretary of state and he put them on a train to Washington.

"By the time they were pushing to try to have another vote, the secretary of state in Washington had already accepted the proof of the election," Cotham said.

How is the letter preserved?

Each page of the Burn letter is stored in protective Mylar sheets and stored in acid-free archival folders and boxes.

Despite rumors that the letter had been destroyed, it has been stored in the McClung Collection since 1978.

It's been scanned and uploaded to the collection's website and copies have appeared in several textbooks. As the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment approache, Cotham said they've gotten requests to view the letter at least once a day.

The collection also has about 250 telegrams Burn received before and after the vote. Some are in favor of suffrage, while others are against.

"It was controversial," Cotham said. "The anti-suffrage group was of the opinion that if women got really interested in politics, it would pull them away from their major responsibility with hearth and home, taking care of children and taking care of families. They were pretty passionate about that.

"The other side, a lot of women were already thinking about being in the workforce, and that was fairly new," Cotham continued. "They really wanted to be part of the bigger public."

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality local journalism like this.

More coverage

Women of the Century: They didn’t succeed despite adversity, but often because of it

50 states: Learn about notable women from every state

Who is your Woman of the Century?: Let us know

Recognizing women past and present: See all of our coverage

Statues bring suffrage history to you

Women’s suffrage is commemorated in many landmarks around the country. Two statues, the Tennessee Woman Suffrage Memorial in Knoxville, Tennessee, and the Let’s Have Tea statue in Rochester, New York, recognize key figures in the movement to ratify the 19th Amendment. Explore these statues in our augmented reality experience, available on your phone and within the Augmented Reality section of the USA TODAY app. Learn more.

19th Amendment coverage

In fight for 19th Amendment, suffragists saw Tennessee as last hope and worst nightmare

Women suffragists persisted for 70 years to win the right to vote in 1920

Famous women's suffrage speeches come to life in augmented reality

‘Be a good boy’ and vote for suffrage: How a mother’s note carried the 19th Amendment

‘Sisters helping sisters’: The surprising role religion played in the women’s suffrage movement

Tennessee suffragists changed history ‘without firing a shot’

Think you know everything about women’s suffrage? Here’s the history to unlearn

Equal Rights Amendment: Will women ever have equal rights under federal law?

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Vote for suffrage: How one note changed history