'Make a good life': At 97, WWII veteran Tonie Darvid doesn't romanticize war

PORTSMOUTH — Tonie Darvid has gained wisdom in his 97 years, which included playing a key role as an Army Engineer in the pivotal landing at Normandy, France during World War II.

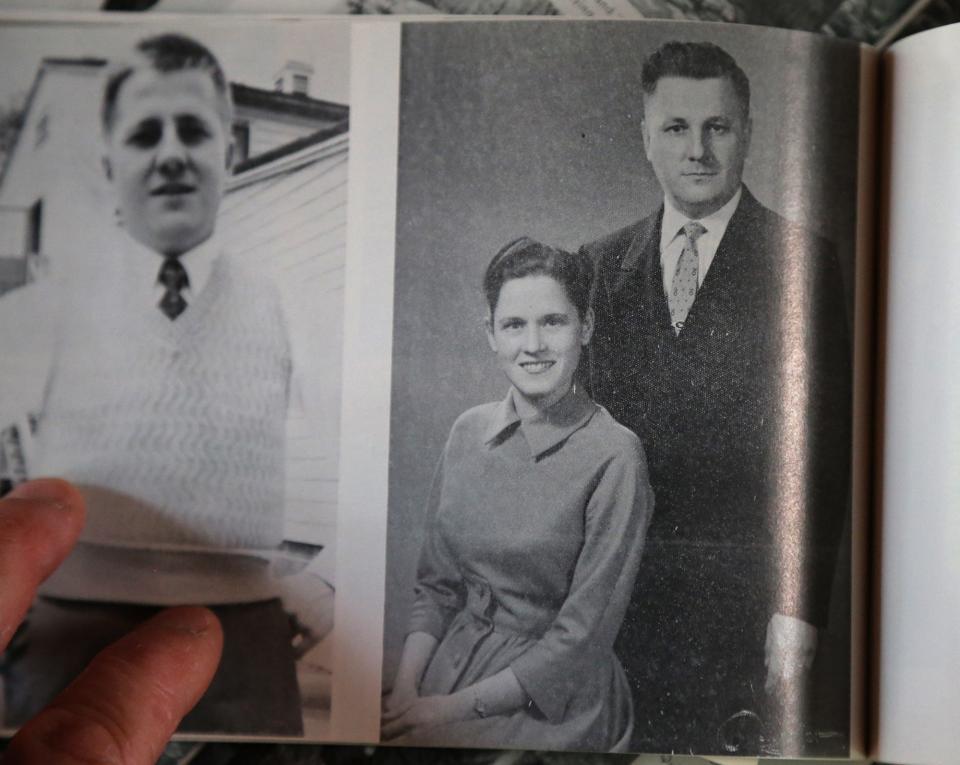

Today, he is content to live quietly with his wife, Elisabeth, who he met while stationed in Germany after re-enlisting at the end of the war. Tonie and Elisabeth have been married 65 years.

After spending 21 years in the service, working at Simplex and many years at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard as a crane operator, Darvid says he has no regrets. He also says there’s nothing on his bucket list left to do. He is content with his daily routines he and Elisabeth share at their small home on Greenland Road in Portsmouth.

Darvid is a storyteller. Sitting on his enclosed porch on a hot July day, he holds a pair of high brown leather boots he wore which still show the stamped serial number “31263108 belonging to Tonie Darvid” on the inside flap.

The Army was a whole new way of life for the boy who grew up in the small town of Easton, New Hampshire, best known today as the birthplace of Olympic skier Bode Miller. There were roughly 130 people in the town when Darvid was growing up and today there are still fewer than 300. He and his five siblings walked four miles to get to school.

“I only went through grade 8,” he said. “The high school was seven miles away and there was no transportation. You couldn’t go there unless you could find someone to take you in.”

The scenic 150-acre Darvid Farm in the White Mountains, where Tonie grew up, was purchased by his Eastern European immigrant parents in 1925, and is now in conservation, donated by Tonie and his sister Anna.

After eighth grade, he moved to Portsmouth to help his brother-in-law with his plumbing business. He was drafted at 19.

“They told me I had one month to get my affairs in order and report back to go to basic training at Fort Devens,” Darvid said.

Training for war

All the men had to strip naked when they got processed, Darvid said. “They just threw the uniforms at us and my shoes and clothes didn’t fit. Yep, we all looked like real sad sacks.”

Basic training was hell but so were all the other training missions they did along the way until they reached the beach at Normandy as part of the massive amphibious Allied invasion that turned the tide of the war.

“I was in pretty good shape, but when I got through bayonet training my tongue felt a foot long from being out of breath. You had to go through obstacles then stab this rubber dummy made with 2x4s and pull the bayonet out before it bounced back and hit you.”

Veterans Day 2021: Seacoast concerts, ceremonies, free meals and more events

Some guys weren’t fast enough and they got knocked out and they would just drag them aside and keep things going.

“We’d crawl through mud on our bellies with live ammunition flying over our heads. Then we’d have to build a pontoon bridge for the infantry and break it down again while wading through icy water and eat the lousiest food you ever ate. Sometimes, it was so cold that if you had a drink of warm coffee, you would shiver so much that you could crack a tooth and it would feel like a guy's arm would reach down in your gut and pull it up."

In August 1943, he joined the Company C 332nd Engineer General Service Regiment located at Melbourne, just outside Burton on Trent, England. The engineers were trained to build bridges, roads and other infrastructure needed by the armies that would eventually defeat the Germans.

In time, the unit was getting equipment ready for the invasion, which took place on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Darvid was assigned a Jeep which he prepared for the invasion by waterproofing the engine so it wouldn’t short out if it got wet. “They took our wrist watches and newspapers; anything that would let us know what time or day it was. We were isolated and had no contact with anyone.”

Darvid's unit reached the beaches about six days after the initial invasion. Their mission was to support the troops by constructing roads, railroad bridges, hospitals; picking mines, anything to help the advancing armies.

According to Wikipedia, "This unit served with several of the Armies of World War II as it was part of ADSEC (Advanced Section, Communications Zone). ADSEC's mission was to support the U.S. First Army, U.S. Third Army, and U.S. Seventh Army by building bridges, roads and hospitals through France, Belgium and Germany."

“When my Jeep hit the beach it was like the 4th of July," Darvid said, describing the fighting. "There was plenty of dead bodies lying around and stuff. The fighting was about 10 miles inland and you could hear the shells coming over and landing in the water and stuff. About three days later, we went to Cherbourg and that was a pretty hot place. ... Anywhere we were needed of whatever came up, we needed to make it easier for the troops.”

One of the most impressive jobs the unit completed was the Victory Bridge at Duisburg-Rheinhausen. They built the bridge in six days, 15 hours and 20 minutes, and it was 2,815 feet long over the Rhine River. That way the troops could cross into vital territory.

"Victory Bridge at Duisburg – Rheinhausen, built in six days, fifteen hours and twenty minutes – then a record – at 2,815 feet (858 m) long over the Rhine River, was completed on May 8, 1945," according to Wikipedia.

What he has learned

At 97, Darvid doesn't romanticize the war or his role in it.

"There was a lot of propaganda but when you see a guy laying down on the ground dead, it kind of makes you think if it’s all worth it, you know? What’s it all about? You find out politics is pretty powerful. All the ammunition and stuff you destroyed. ... It’s all decided by the stroke of a pen. ... I was just a political pawn just like anybody else who got caught in this confusion about the war and so forth you know we got shipped over there to kill. We had no reason to kill because we weren’t actually enemies. We didn't know each other and the guy didn't do anything to me and I didn't do anything to him but I was shipped over there. I was taught how to kill and I was taught to forget about my emotions. I was taught to be a killer.”

Darvid said a key to his survival during the war was making himself think like the enemy.

“You had to use your intelligence and be very careful. When I was picking mines, you make your own tools, and then you try to analyze your enemy. Where would he put that? How would you do that if you was him? Usually if you take your time you’d be able to analyze his character. You’d say you had two choices his and yours so you’d have a foot ahead of the situation. You were mostly right. One day we lost five guys because of their stupidity not using caution.”

There was also a time Darvid got wounded when he and his unit strayed too close to the German border that was still being defended. He still has some shrapnel in his knees.

“We were running through the field into some woods and I could hear rifle shots. A rifle round must have hit a tree or something. The guy didn’t shoot high enough and it went straight past here” he motions to knees. “You can feel it; it’s the black spot. A week later I got gangrene. I wanted to get out of the place I was sleeping ... it hurt so much I fell on the ground. They gave me some hydrogen peroxide. I had a red streak all the way up to my groin. They pulled out the stuff and drained it and kept going.”

In response to a question about whether he believes he survived due to divine intervention, Darvid tells a story.

His unit was outside Liege in Belgium. They were sleeping in abandoned box cars because the ground was so cold if you slept on it you'd never get up, he said.

"These guys invited me over their place where they made potato liquor with our potato peelings. It had no taste but it had a lot of kick. It was powerful. I felt my nose and ears getting numb so I figured I’d slack off. ... I was going back where I lived and it was dark and something told me to jump over the hedge and get up against a foundation of a building. All of the sudden I could see anti aircraft and they were shooting at a plane and pretty soon the shrapnel fell over the path I was walking. You don’t know what tells you these things, but instinct must grab a hold of you and tell you what to do.”

After 97 years, Darvid says he still can't tell you life's purpose.

“I don’t know what the purpose is," Darvid said. "Nobody really knows. I will say it seems to be like a big joke because we are being fooled all the way. We take everything for granted but when the time comes and you find out you were fooled all your life. Because you were thinking tomorrow will be a better day as you get older you don’t heal as fast and the good Lord doesn’t give you anything. He wants everything back at the end of the day. Nothing is yours. Not even a breath of fresh air. You have to fight for it to live another day. Nothing is yours; not even a kiss. Not even a hug. It’s yours only for a moment.”

When the war was over, Darvid left the Army for just three months and then re-enlisted. Due to PTSD on his return, he felt out of place and said he felt he didn’t fit in. His hands would shake while drinking coffee or eating a sandwich in a restaurant. He says after returning to the service, he felt more at ease. He was stationed in Germany for the next three years where he learned to speak the language. He also speaks Polish. He also met his German wife, Elisabeth. It took Tonie two years to bring her to the United States in order to get her cleared of suspicions she might be a spy and other concerns after the war. They got married in Manhattan at City Hall since their families were so far away.

Eventually he was stationed in NYC to a VIP pool where he drove generals, civilian leaders and foreign dignitaries from all over the world. “I would go to the airport to pick them up. The first one I got assigned to was Herbert Hoover. I picked up all different kinds of people.” Some others were the American Ambassador to Spain, Angier Biddle Duke who was famous for swimming in the Mediterranean after a B52 carrying plutonium crashed so he could convince people it was safe. He was assigned to Anthony Clement "Nuts" McAuliffe who earned his fame defending Bastogne, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge and his nickname by giving that one word reply when the Germans asked if he would surrender.

And he drove for Eleanor Roosevelt.

“She was the motherly type and was the nicest person you’d ever met. I think she ran the United States (while) Roosevelt made his occasional appearances on TV."

Does Darvid have any advice on how to live a better life?

“I would say get a job, read, study and make a good life for yourself," Darvid said "Don’t depend on other people for your welfare. Do it yourself and learn as much as you can and listen to a guy that gives you good advice.”

This article originally appeared on Fosters Daily Democrat: WWII veteran Tonie Darvid doesn't romanticize war