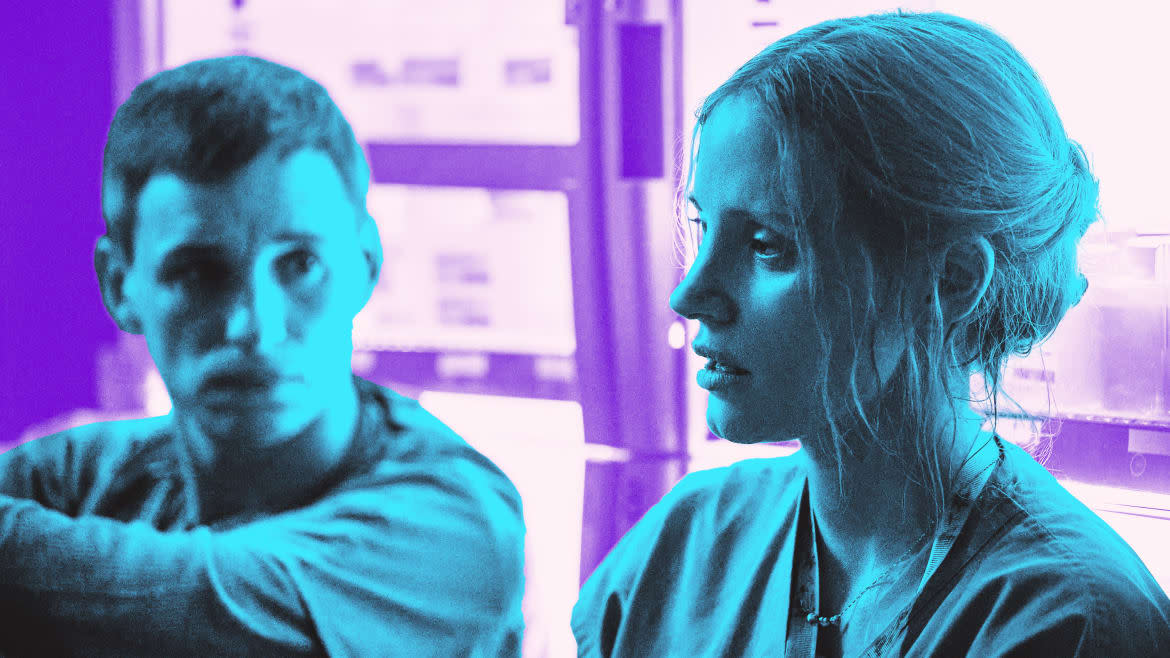

The Good Nurse’ Gives a Sadistic Male Nurse Who May Have Killed 400 People the Hollywood Treatment

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Charles Cullen was sentenced to 18 consecutive life sentences for the deaths of 29 people and, over the course of his 16-year nursing career, he may have been responsible for as many as 400 murders. Given his prolific awfulness, then, it’s too bad that The Good Nurse, Danish director Tobias Lindholm’s adaptation of Charles Graeber’s 2013 book about his capture, is so muted and listless. Handsomely mounted and featuring gripping performances from Academy Award winners Eddie Redmayne and Jessica Chastain, it’s a thriller that—for better and, too often, for worse—plays like a stifled scream.

The Good Nurse (on Netflix Oct. 26) opens in 1996 Pennsylvania with Charles (Redmayne) staring blankly at a flatlining patient, Lindholm’s camera zooming in to gaze into the hospital nurse’s passive eyes. That stare, as well as a slightly hunched posture in which his arms barely swing as he walks, imply that something is terribly wrong with Charles. Redmayne ably evokes the man’s inner vacancy as well as his ability to mask that hollowness with a façade of cheer, and Charles subsequently comes across as a rather friendly and accommodating health care provider to fellow nurse Amy Loughren (Chastain) upon beginning a new job at a New Jersey hospital. For Amy, who’s dealing with a potentially fatal heart condition, Charles is a godsend, more than willing to help pick up her slack both at work and at home, where she’s struggling as the single mom of two young daughters, the older of whom resents her constant absence.

Netflix Just Dropped a Horror Anthology Series That Is to Die For

Amy is a kind and caring presence for her patients, including an ailing woman who can barely take a painless sip of water, and considering Charles’ supportiveness, Amy is more than willing to put her and others in his care. The Good Nurse’s aesthetics, however, suggest that something sinister is simmering beneath its placid surface. Partnering with cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes, Lindholm coats everything in the subdued blue-gray hue of ER scrubs, and he routinely frames his characters in doorways, hallways. and other constricting structures to amplify his claustrophobic atmosphere—all while simultaneously stranding silhouetted figures in empty space. From a formal standpoint, including with regard to Biosphere’s foreboding score, the film is strikingly manicured, albeit to a degree that asphyxiates any air of suspense.

Red flags appear when detectives Danny Baldwin (Nnamdi Asomugha, formerly of the NFL) and Tim Braun (Noah Emmerich) are called to the hospital by a risk officer (Kim Dickens) who wants them to look into the aforementioned patient’s unexpected demise, which happened when both Amy and Charles weren’t on duty. What’s strange isn’t that the administration is concerned about this death but that they’ve already conducted a seven-month internal investigation into the matter and won’t turn it over to the cops. They also won’t allow them to speak to any staffers without having Dickens’ executive present, all of which makes Baldwin suspect that a cover-up is afoot—and that the motivation is money.

While Baldwin and Braun are puzzled about what’s going on here, The Good Nurse so doggedly fixates on Amy and Charles—the latter of whom resembles a sociopath pretending to be a sympathetic human—that there’s no real mystery regarding who’s responsible for the untimely passings that become a regular occurrence in the duo’s ER. The question is only how Charles is committing his crimes, and when Amy will deduce that her new BFF is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The latter of those two queries is answered by the film’s midpoint, when Amy’s clandestine review of medical files reveals that her hospital’s inexplicable fatalities are the result of lethal increases in insulin levels—something that could only be caused by mistaken (or deliberate) doses of unnecessary drugs.

As a tireless professional trying to do right by herself and her kids, Chastain is magnetic enough to keep one invested in Amy’s personal and Charles-related plights, even as The Good Nurse eventually opts to take a cheesy route by having her temporarily land in his medical care—a wannabe-anxious twist that, like everything else about the film, is handled with a somber gravity that smothers tension. Chastain radiates warmth and kindness. but the material is too downcast to let it shine through, and as a result, even her friendship with Charles feels low-key and ho-hum. It’s Asomugha who truly cuts through the gloom to deliver a captivating turn as a sleuth intent on proving that which he knows to be true, and his scenes with Emmerich and Dickens wind up being the proceedings’ early highlights.

The Good Nurse is the story of a bad man and the noble woman who—upon learning of his evil—attempted to stop him, although nestled within that narrative is a more intriguing portrait of institutional villainy. Krysty Wilson-Cairns’ script paints hospitals as akin to the Catholic Church, shuffling off its wrongdoers to new facilities (rather than alerting the authorities) as a means of avoiding liability. It’s a fundamentally corrupt system that places profit above all else, as similarly evidenced by the fact that ailing Amy stays on the job (regardless of the hazards to her health) in order to qualify for insurance. Unfortunately, though, the film doesn’t elaborate on that thread, choosing to merely point a damning finger before turning its attention back to Charles and Amy’s dynamic, which is complicated by Amy’s recognition that her buddy is a monster (who’s injecting unnecessary narcotics into IV bags) and her ensuing collaboration with Baldwin and Braun to coax a confession out of him.

Whereas Lindolm’s prior Another Round brimmed with exuberant life, The Good Nurse is stately, economical and mechanical, going through its true-crime motions with maximum polish but minimal excitement. A late outburst by Redmayne’s Charles shatters the monotony, exposing the incomprehensible mania compelling the man to assassinate the sick and elderly. That gesture, however, is too fleeting to make a lasting impact, and the film’s textual-coda admission that Charles never explained why he killed so many—this coming on the heels of sketchy hints that he was driven by traumatic mommy issues—is in keeping with action’s general opacity. Redmayne may effectively convey the frightening void within Charles, yet Lindholm’s English-language debut never plumbs its depths.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.