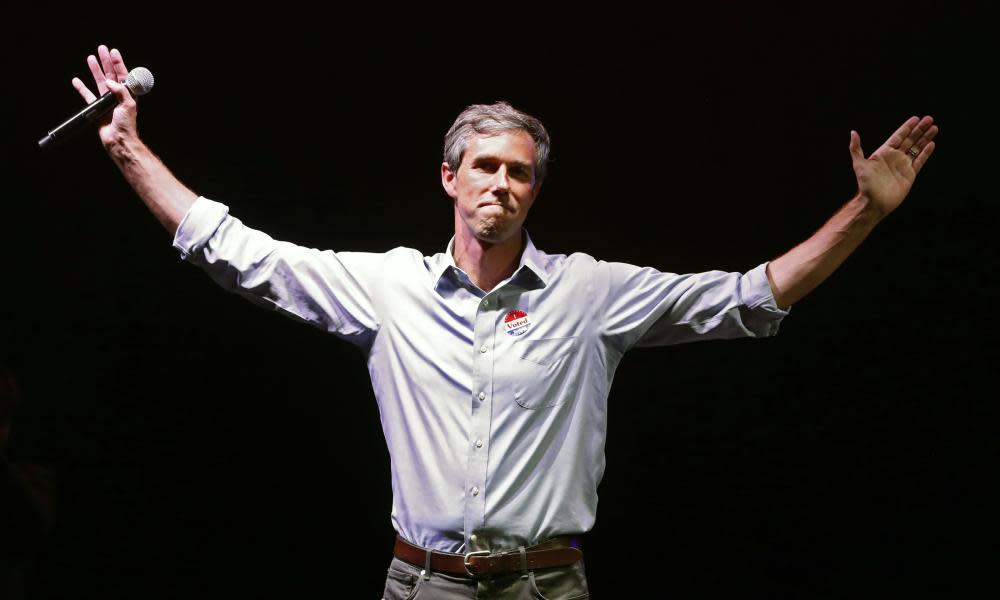

Goodbye, Beto O'Rourke. What a sad end to a pointless campaign

When Bernie Sanders was first asked about Beto O’Rourke entering the presidential race, his reply was dismissive: “Free country, anybody can run.” But others thought O’Rourke was a powerful new rival. The New York Times said that Sanders’ “stronghold on the party’s progressive wing has weakened” because he was now “outflanked on the left by rising stars” like O’Rourke. O’Rourke debuted with a splash: a long, flattering profile in Vanity Fair in which O’Rourke—to his later regret—said “Man, I’m just born to be in it.”

He was not, as it turned out, born to be in it.

After the initial burst of publicity, Beto fizzled quickly. His poll numbers never got out of single digits, and at first he didn’t seem to know what he stood for or why he stood for it. Eventually, he hit upon a signature issue: gun control. But his provocative rhetoric—“Hell yeah, we’re going to take your AR-15”—seemed to backfire entirely, and he was accused of “hurting the cause” and even “single-handedly dooming a gun control bill.” He continued to lack a following outside of Texas, a place where he could not even win a statewide election against the Senate’s most reviled member. Perhaps the only person who ever truly thought Beto O’Rourke was likely to be president was Beto O’Rourke.

What, if anything, can we take from the brief, underwhelming presidential run of Robert Francis O’Rourke? First, media hype does not a candidacy make. Jennifer Rubin of the Washington Post declared in March that “Beto fundraising number[s] suggests Bernie now officially yesterday’s news, faces stiff competition for youth vote.” Indeed, Beto initially hauled in an impressive amount. But things change quickly in politics; remember that Rudy Guiliani and Jeb Bush were both once Republican Party frontrunners. Horse race pundits like to issue declarations and prophecies, but are just speculating. Political media is in constant need of new stories to tell, so we get a lot of “Could Candidate X Be The Next Big Thing?” coverage. The sensible thing to do is ignore most of this. Beto-mania was never likely to grip the country.

We might also learn quite a simple lesson, namely that if you’re going to run for president, it helps to have a good reason for it. A reason beyond being “born to be in it,” that is. The Vanity Fair profile in which Beto debuted his national run was full of personal details about his life, such as his reading habits and his love of punk rock, but he didn’t say much about what he wanted to do as president, beyond having the United States “lead the world.” He also voiced uncertainty about being “against” things, saying he preferred to be “for” things, which is fine if you specify the things you’re for, but also a worrying sign that you’re insufficiently outraged by injustice. You’d think even Beto could have said he was against that, but he wouldn’t even go so far as to say he was a progressive, saying he “[didn’t] know” and was “not big on labels.”

Beto’s campaign suffered from the same defect as Hillary Clinton’s. Insider accounts confirmed that Clinton could never really find a clear reason why she was in the race to begin with, and didn’t have any kind of clear agenda in mind. It was mostly that she just wanted to be president, and felt like the sort of person who ought to be president. Like Pete Buttigieg, who talked about having the right “alignment of attributes” for the job—for him, an Ivy League education, military service, and small town heartland authenticity—both Clinton and O’Rourke emphasized their personal traits over their political ideas. But people want substance: they need to know what you plan to do for their lives, not just why you’re a cool person with the kind of haircut that the president might have in a movie.

Beto’s run always seemed like an ego trip. His family did not seem nearly as enthusiastic as he was about it, and his young son promised to “cry every day” if O’Rourke went through with it. He got into trouble for casually joking about putting the burden of parenting on his wife as he criss-crossed Texas campaigning for the Senate. But fame and power are alluring, and O’Rourke was one of dozens of politicians lured into the 2020 race by the promise of a national profile and a shot at the highest office. A slew of nondescript white men, including John Delaney, Michael Bennet, Tim Ryan, Seth Moulton, and John Hickenlooper, were delusional enough to think they might stand a chance. They might not have been that irrational, though: even in failing, they succeed in making themselves more well-known and possibly even more influential.

They’ll all go eventually, though. With no original ideas, no movements behind them, they have nothing to offer the electorate, and the electorate knows it. Beto O’Rourke should never have run for president, but he couldn’t stop himself, because some men are just convinced they’re born for it.

Nathan Robinson is the editor of Current Affairs and a Guardian US columnist