Google's 'Stadia' Is the Latest Attack in the War on Games You Can Actually Own

Say you want to sit down and play some classic Super Mario Bros. or a couple levels of Sonic the Hedgehog. There are countless remakes and streaming options to choose from (some of which you must pay for), but the old standby is always an option: You can plug your old cartridge into your old console into your old TV, and it'll just work.

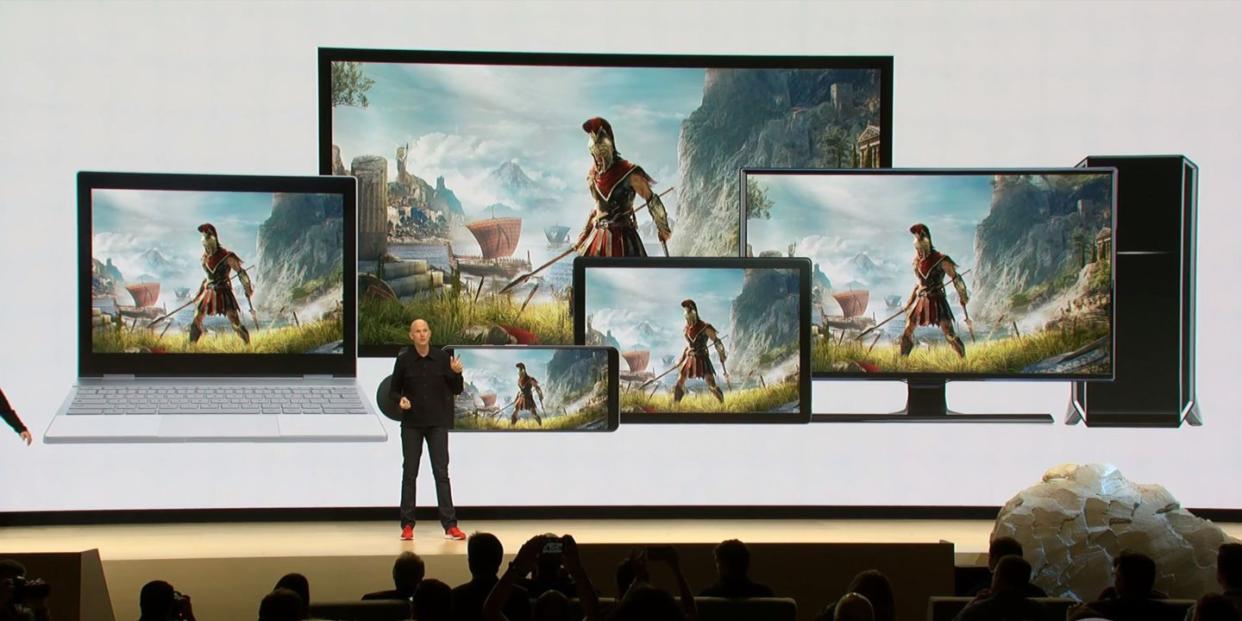

If that sounds quaint, it should. Over the past decades, video games gradually have been turning into something more amorphous that can change over time, and can disappear forever. Google's Stadia, announced today at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, could be the next step away from those classic roots.

At its core a streaming service, Stadia is the Netflix to your DVD collection. It's way to transport games that are running on datacenter computers miles away into your living room with ease. All it requires is Chrome, which means your computer with mouse and keyboard is ready to launch games directly inside your browser, while your TV just requires a Chromecast and a controller, either Google's special one or a variety of supported third-party options you might own already.

The upsides are obvious: If it works as advertised, with near imperceptible lag, then every internet-screen in your home is suddenly a super-powered game console running amazing graphics on computers you don't have to own. But the downside is that idea of games as creative works that can be complete and which you can own is slipping further away.

From the Cartridge to the Cloud

For the first decades of the gaming console and PC boom, games were released in static form by sheer necessity. Cartridges, diskettes, and CD-ROMs all contained full, unchanging versions of games that were forever compatible with the similarly stable hardware they were designed to be played on. And then the internet changed everything.

First on PC, but eventually consoles, the proliferation of the internet made it more and more feasible-and sometimes necessary-for developers to change their games after the fact. Patches, as free and minor updates are called, became a valuable tool for smoothing out glitches that, in a previous era, would hamstring games for eternity.

But then bug-fixing patches evolved into paid "downloadable content" that expanded games after the fact, which would soon transform the way games are sold. Digital storefronts like Steam and Xbox Live selling digital versions of the latest games replaced brick-and-mortar storefronts selling physical ones. This transformation replaced the notion of a personal game library as a shelf in your basement containing static, self-contained copies of games with an online account associating a list of every-changing titles with a username.

The modern model brought considerable advantages, from buying games without leaving the comfort of your own home to creating an ecosystem of online games that are constantly updating with new features and levels, increasingly for free (with optional purchases, of course). Google's Stadia promises to lean into those conveniences. With no specialized hardware involved, there is no entry-level fee for a console (though Google is still mum on exactly how pricing will work). And since games are streamed rather than run locally, they can be played instantaneously with no download time, potentially even launched from inside a YouTube video. With the power of Google's cloud behind them, Stadia games could revolve around feats of computing no current home-console could ever hope to accomplish, like 8K resolution or thousands of simultaneous players in the same game.

Like It Or Not

Google isn't the first to promise this future. Ten years ago at this very same gaming conference, a company called OnLive promised many of the same things before collapsing roughly five years later after the necessary low-latency tech failed to materialize. Google won't be the last either. Microsoft is revving up to tackle the same space with its $10-a-month Xbox Games Pass and a similar cloud-based platform on the horizon.

But even if the tech does shake out this time around (for people with access to adequately fast internet connections, at least), and even if the result truly is wide access to a broad swath of games for a lower price than buying them all outright, there is a hidden cost. The price of this convenience is a sometimes subtle but always extreme loss of control, made briefly visible when an online game is threatened with annihilation as its official servers go offline, or a marketplace closes its doors and cuts former customers off from the games they had thought they purchased.

Google's Stadia is the logical conclusion of an evolution in which games and their marketplace merge, and you never really own them at all. For better and for worse, we are careening down this road.

('You Might Also Like',)