'We got hung juries and acquittals' in 1960s Mississippi civil rights murder, attorney says

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Gene Livingston was an aspiring young attorney who had taken a job with the U.S. Department of Justice a few months before he was sent to Mississippi to speak with civil rights activist Vernon Dahmer in 1966.

That conversation never took place.

When Livingston arrived at the Dahmer home in the Kelly Settlement near Hattiesburg the morning of Jan. 10, he found himself in the midst of a crime scene.

As Livingston tells it, he was sleeping comfortably in his hotel room while the Dahmer home was firebombed and shots were exchanged between Dahmer and members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

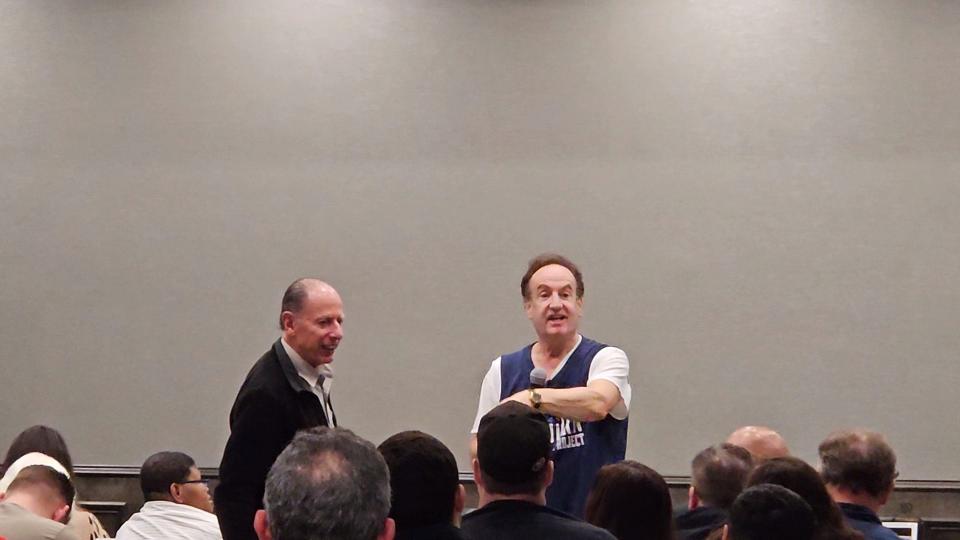

Livingston, who lives in Davis, California, with his wife, Carol, was in Hattiesburg this week with a group of students from the Sojourn Project, to learn about history where it took place.

For subscribers:Parchman visit brings fear, relief to Mississippi Freedom Rider who was imprisoned as a teen

The high school students and members of the San Francisco Police Department visited the Kelly Settlement where they were able to talk with members of the Dahmer family who witnessed the firebombing and Dahmer's eldest son Vernon Dahmer Jr., who was in the Air Force at the time of his father's death.

"What did we study today?" Sojourn Project founder Jeff Steinberg asked the students.

The students responded together, "Vernon Dahmer." A few more Dahmer family members were listed, as well as former Clarion Ledger investigative reporter Jerry Mitchell.

"He broke open the cases," Steinberg said.

Courage in face of hate: Slain civil rights leader Vernon Dahmer, 8 others honored

Dahmer, his wife Ellie and three of the couple's children — Harold, Dennis and Bettie — were inside the home when the klansmen arrived. As Vernon Dahmer singlehandedly fought off the Klan, his wife and children were able to escape.

Vernon was badly injured in the housefire and died later that day from his injuries. Bettie also was injured but was able to recover from her wounds.

"There was yellow tape everywhere," Livingston said. "And investigators. I stuck around for a day or two."

'Devotion':Movie chronicles the Navy's first Black pilot. Jesse Brown's family reflects on his life

Once back in Washington, D.C., Livingston was able to follow the Vernon Dahmer murder investigation through FBI reports.

By June 1966, the FBI had gathered statements and some confessions from the people believed to be involved in the firebombing. The DOJ was ready to move forward with prosecution.

"We were able to present the case to the grand jury," Livingston said. "We got indictments against 18 people or something like that."

Livingston did not participate in the trial in Dahmer's case, but kept himself informed of the progression. Things did not go well.

"You know, when they did try that case, they got hung juries and acquittals," Livingston said.

The fight for justice in Dahmer's murder continued. More than 30 years later, a jury found the White Knights' leader Sam Bowers responsible for Dahmer's murder. He was sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 2006.

Bowers also was accused of ordering the murders in 1964 of three civil rights workers, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, in Neshoba County. He was convicted but served less than 10 years in prison for their deaths.

Dahmer, who was Black, became a target of the Klan for helping other Black residents in Forrest County register to vote. Dahmer, a farmer and grocery store owner, would pay the poll taxes for those who could not afford it themselves to make sure they would have the opportunity to vote.

"If you don't vote, you don't count," Dahmer was known for saying.

Livingston worked in the DOJ's Civil Rights Division. He had been sent to Hattiesburg to talk with Dahmer about the many barriers hopeful Black voters still faced, despite the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Livingston worked with DOJ attorney John Doar, who was the lead attorney in voting discrimination case against then-Forrest County Registrar of Voters Theron Lynd, accused of denying Black residents the right to vote. The case was won on appeal, but Lynd allegedly ignored the appellate court's order.

Do you have a story to share? Contact Lici Beveridge at lbeveridge@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @licibev or Facebook at facebook.com/licibeveridge.

This article originally appeared on Hattiesburg American: Former DOJ attorney visits Mississippi, talks about Vernon Dahmer case