How we got here: Louisville’s high-water history and the aging levee system standing guard

A 26-mile wall of concrete and earth, born of death and disaster, shields Louisville from the Ohio River.

It wasn't until Louisville had been swallowed up by muddy waters — more than once — that it was built. Now, some parts of the flood protection system are operating decades beyond their retirement age, even as projected risk of extreme rainfall and flooding grows. Funding for improvements has been elusive.

This bulwark against natural disaster has not always been there. Soon, it may not be enough. How did we get here?

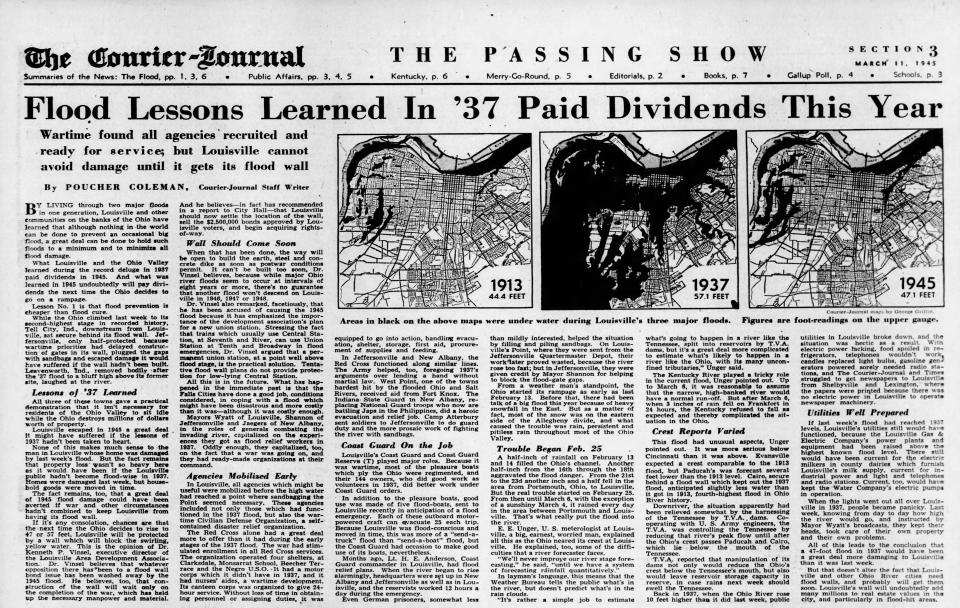

1937

In the cold of January and the Great Depression, the icy waters of the Ohio encroached on Louisville, a city without flood protection. No bigger disaster has befallen the city since.

An estimated 175,000 residents were forced from their homes, fleeing to high, dry ground. Others waited on rooftops for help, as boats rowed through the streets.

Much of Louisville’s West End and downtown were submerged beneath 10 feet of water. A majority of the city was inundated, including the track at Churchill Downs. In true Kentucky fashion, residents built a pontoon bridge of whiskey barrels between downtown and the Highlands.

With the muddy Ohio filling the streets, typhoid became an even bigger threat. Medical staff worked out of makeshift clinics in a large-scale vaccination drive, reportedly reaching more than 200,000 residents.

After days of inundation, the waters began to recede. Dead livestock were found lodged high in the branches of trees. A fish, purportedly caught in the lobby of The Brown Hotel by the bell captain, was mounted on the wall.

Mayor Neville Miller reported 190 deaths tied to the disaster, which would come to be known as Louisville’s Great Flood. As the river retreated to its banks, it revealed damage worth more than a billion of today’s dollars and a clear and urgent need for flood protection.

Louisville would still host the 63rd running of the Kentucky Derby in May, just months after the Ohio River had swamped the track.

1945

As the nation focused on the final months of a costly war overseas, another flood hit Louisville, still without flood protection in place.

To this day, it was the second highest crest of the Ohio River on record, though still 10 feet below 1937's deluge. But Louisville had learned some lessons from 1937. Some at-risk buildings had been built up after flooding the first time, and residents were more prepared when waters began to rise.

Still, it reminded Louisville of the risk inherent to all river cities, and reinforced a desire for protection. Locals called for flood infrastructure to be built “as soon as postwar conditions permit” in the pages of The Courier Journal. “Lesson No. 1 is that flood prevention is cheaper than flood cure.”

A few years later, after the war, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would begin construction on the wall, designed to make sure 1937 never happened again.

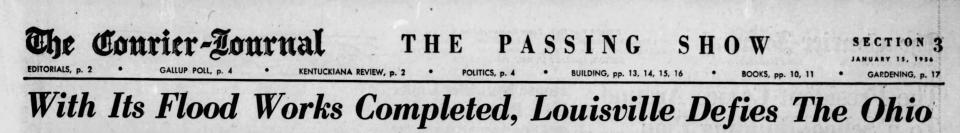

1956

Nearly two decades after Louisville's Great Flood, the Corps finished its first segment of flood protection infrastructure. It stretched from Beargrass Creek in the east, tracing the bank of the Ohio around the city through Rubbertown in the west.

Thick concrete walls cut through Butchertown and downtown, with placements for street closures in the event of flooding. To the west, a tall earthen levee continued the jaunt around Portland and southward. The barrier was built up to the height of the historic 1937 flood, plus a few extra feet.

Pump stations dotted the path, designed to pick up rising inland water and send it into the Ohio. The Beargrass Creek pump station, at the time of construction, was one of the largest in the world.

The following year, the city and county governments became responsible for the system's operation and maintenance. This would not always be the case.

1964

Less than a decade after the first segment's construction, Louisville's shiny new flood infrastructure faced its first major challenge — and failed.

After multiple street closures didn't go up in time, the river rolled into downtown, prompting the Corps of Engineers to take over from local Public Works.

Corps records would later suggest that the system was only loaded to 45% capacity from the 1964 flood, which was more than 10 feet short of the 1937 crest. The Ohio has not risen to higher levels since, leaving the flood protection system relatively untested.

1987

Louisville's Metropolitan Sewer District took over maintenance and management responsibility for the flood protection system in an agreement with local government.

1989

Just a few years after responsibility for the flood protection system changed hands, the Corps of Engineers completed an expansion, stretching south to the border with Bullitt County and nearly doubling its length. The addition made the system 26.5 miles long in its entirety.

1997

In early March, Louisville's flood infrastructure was put to the test as the Ohio rose to major flood levels for the first time since 1964. It was MSD's first major test as operator of the system.

More than 12 inches fell in just a few days. In this flood, the worst came to Louisville's South End.

2018

The region's biggest flood so far this century arrived in February. Over a five-day span, Jefferson County got about 8 inches of rain, putting many outlying communities underwater.

More than one of MSD's pumps broke down in efforts to keep up with rising inland waters, and cars were stranded in swamped streets. The Ohio River, which crested more than 16 feet below 1937 levels, was kept at bay by the levee system.

MSD later reported pumping about 26 billion gallons of water out of the city during the flood event.

2020

In October, Lt. Gen. Scott Spellmon, chief of engineers for the Corps, approved a $188 million plan to reconstruct parts of Louisville's flood protection infrastructure, with an emphasis on vulnerable pump stations. The chief's report came after a thousand-page feasibility study, which picked apart existing flaws in the system.

Two months later, Congress passed the biennial Water Resources Development Act, authorizing the project Spellmon approved. This gave MSD and the Corps a green light to pursue funding for the work itself.

2022

Congress passed a $1.7 trillion omnibus spending package to prevent government shutdown — without including funds for Louisville's flood infrastructure. This left Louisville to compete with many other projects nationally for a limited federal funding pot in early 2023.

2023

In March, the Corps announced $1 million for designing improvements of the flood protection system, in addition to contributions from MSD. Tony Parrott, executive director of the sewer district, called it a "down payment."

It's a small dent in what's needed. A 2017 estimate of costs to fund recommended improvements to the system was about $640 million over 20 years, and MSD said that number has increased significantly, at least by 20-30% since then.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: When was the big flood in Louisville and what has happened since?