‘You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there’

It should have been impressive, the stack of evidence.

One eyewitness identification by a September victim, who said she recognized her attacker on the street. Reinforced when she also picked him out of a photo lineup, and then by identifying his voice.

Add to that one badly failed polygraph test.

“He agreed to take one, and he flunked it flat,” said prosecutor Ray Robertson in 2019, recalling those fraught days in Staunton in the late 1970s. The test would not be admissible in court as evidence, but “it helped convince the police that they had the right guy.”

Add a record of questionable behavior turned into a trail of misdemeanors.

It equaled one man behind bars at the local jail in what appeared to be a slam-dunk case.

Ray Robertson should have felt confident about catching the city’s “stocking mask rapist” — a Black suspect named Teddy Gray.

The prosecutor knew in his gut it was all wrong.

Eyewitnesses made mistakes more often than people thought. The history of DNA evidence has shown the most common cause of false conviction and imprisonment has been incorrect eyewitness identification. “Especially the victim identifying the defendant and getting it wrong,” said Robertson. And Robertson thought most people don’t understand polygraphs. “They show deception, but they don’t show that you’re lying or what you’re lying about.”

Polygraph measures heartbeat, blood pressure and galvanic skin response. “And when they got to the relevant question, did you rape [the Vine Street victim], and he said, ‘No,’ everything went crazy like he was lying.”

Gray thought it was his look-alike brother who did the rapes, according to Robertson.

“And it wasn’t him, either — but that’s what he thought.”

To Gray, it could have made sense that the victim thought it was him. “And so he thought he was hiding something and holding something back and therefore deceiving. That’s why his heart rate and his blood pressure and his galvanic skin response all went haywire.”

Adding to Robertson’s uncertainty was the Oct. 2, 1979, sexual attack, matching in all ways the methods and behavior of the rapist.

And it couldn't have been Teddy Gray, the prosecutor knew. “He was already in jail.”

Robertson thought Gray’s attorney, an older gentleman from Richmond, was not competent and wouldn’t do the defendant any favors. “I saw him in action during the preliminary hearing and so forth. And I was afraid. Teddy wasn't really getting the best representation he could.

“I had real misgivings about Teddy Gray going to trial in Staunton, Virginia, in 1980 for raping a white woman.”

So he kept delaying the trial. He knew the potential spectacle that a trial could be. Virginia was just a few decades removed from white criminals lynching their Black neighbors for trumped-up crimes against white women.

“Racial issues are a bit different than you have now,” he said, looking back. “You’re talking 40 years ago.”

*

Staunton’s city council meeting Oct. 11, 1979, was stormed by “40 angry women,” according to the following afternoon’s paper. The women demanded the city council bring in additional resources to catch the stocking mask rapist before another woman was assaulted.

City Manager Gene McCombs surprised everyone by saying that “outside police specialists” had already been brought in to help.

News-Virginian reporter Brower York Jr. accused the police of lying to him on more than one occasion and withholding information from the news media.

“Half the population is fearing for their lives,” Martha Murphy said during the public comment session.

“Another speaker criticized the police for publicizing the arrest and jailing of one rape suspect whom the police knew was not responsible for all the assaults,” the Leader reported. “By not releasing the latter information, police endangered the lives of women who had relaxed their precautions, the speaker said.”

The next morning, the fourth rape victim testified for a grand jury against Theodore Gray, providing chilling detail of the trauma of the September attack by someone unknown to her.

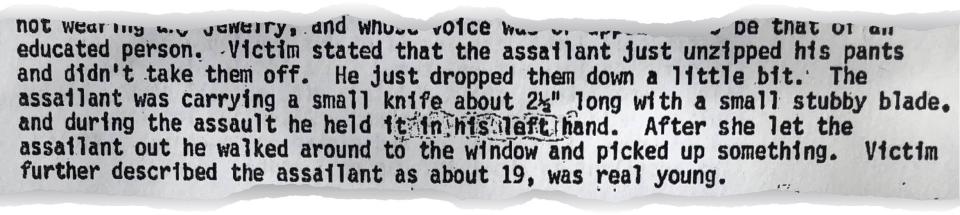

After putting the children she was babysitting to bed upstairs, she’d fallen asleep on the sofa watching television. She woke around 12:30 a.m. feeling the cold metal of a knife against her throat and saw a man with pantyhose pulled over his face. She struggled to get away.

“He told me he would kill me, and I stopped struggling,” she told the court. “He pulled up my dress and raped me.”

The attacker, who she identified as Black, didn’t take her clothes off or tell her to undress. She told the rapist she had venereal disease and was pregnant. “I didn’t want to see anyone go through this thing if they don’t have to,” she said. She tried to feel his features through the stocking mask, and told the court, according to the Leader story, that “Gray’s eyes, lips, nose, voice, shoulders, chest, body hair, height and weight matched that of her attacker.”

She had seen Gray walking in front of Thornrose Cemetery on the west side of town a few weeks after the attack.

Two days later, Staunton Mayor S. Wilson Sterrett said he had confidence in the police despite the criticism of their methods.

“Unhappily,” he added, admitting that the most recent arrest did not stop the rapes, “I cannot report that an arrest is imminent.”

Still, Gray remained in jail. The wheel of justice continued to grind slowly against him, pulling him deeper under the weight of a system that seemed to think it was fine to incarcerate numerous Black men for the crimes of a sole offender. If justice is blind, what it chose not see when indicting Gray was not color but everything else happening outside its halls, including a violent rape of another woman by a man with a knife and a stocking mask.

Capt. Bocock spent most of October defending himself and his force against accusations of lying. “We have not told the press lies. I have not told the press lies. The people don’t know the facts of what has been done and what is being done. They don’t realize how hard it is to catch a loner,” Bocock told the press. But he didn’t seem to want any help; earlier, Bocock had warned that it might be dangerous if women decided to arm themselves with guns and patrol the streets like vigilantes.

He confirmed that reports of the earlier rape at Mary Baldwin and the attempted assaults at Stuart Hall were delayed for weeks at the request of the schools.

And he admitted to asking The Staunton Leader to sit on news of the Vine Street rape for days while the police followed up on leads the captain would not detail.

By the following Tuesday, Oct. 16, the grand jury had officially indicted Theodore Gray for the Vine Street rape, despite the fact that another rape by a man in a stocking mask had occurred while Gray was sleeping in a jail cell.

Gray would spend over 70 days in jail awaiting trial. It would take professionals from outside the local police force to provide the political cover needed by the state to drop the charges on him. That came from an employee of the state police force who happened to live just outside Staunton.

*

He’d later call it one of the most important cases he had in his career. But when he first arrived in Staunton, Special Agent Darrel Stilwell of the Virginia State Police could have called it a mess.

He saw multiple rape cases assigned to different detectives, another to a patrol officer. He saw break-ins with a sexual component assigned to other officers.

The special agent told chief investigator Capt. Bocock, “I want you to bring in all the case files of all five of these rapes, and we’re gonna get in a room and we’re going to go over that, and we’re going to see what we got.”

They gathered each morning and went over every detail of the cases. It was “something that should have been done a lot sooner,” Stilwellsaid in a 2021 interview. There was “very little, if any, coordination” in the investigation of a list of cases that seemed to grow every few weeks.

Picture a dozen sheets of paper taped and glued together and folded up like a map. In a sense, it was a map — it was the first attempt by the police, led by Stilwell, to chart the crimes and territory of Staunton’s stocking mask rapist. The streets he walked; the times he struck; the clothes he wore, the things he said, the objects stolen or disturbed during his break-ins and thefts.

It was the map that would guide them, Stilwell hoped, to end the city’s nightmare.

After three long days of meetings, Stilwell told the chief of police, “You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there.”

He formed a surveillance team. This included the two detectives, Lacy King and Ronnie Whisman, who’d been most involved up to this point. “Those guys were good detectives, I want you to know that,” he said. They hadn’t made much progress, but Stilwell thought this was due to mistakes above their pay grade. King and Whisman weren’t even assigned all the cases that were clearly connected.

They knew the most about what had happened, so they formed the core of his team. He knew he needed more, so he added two patrol officers, L.M. Kerr and D.R. Myers.

“That made five of us,” he said.

The team began focusing on the stocking mask rapist’s geographical footprint. Almost all the buildings he broke into were within a five-minute walk of each other.

“I was sure that guy would be on foot,” Stilwell said.

Night after night they parked in the areas they considered the rapist’s territory. They sat in cars mostly. At times they’d get out and walk a few blocks and come back.

They got to know the neighborhood, which people went out to get exercise at what time of the night. They listened for the difference between the rhythmic sound of a jogger’s stride and the stop-and-start steps of a person pausing while their leashed dog sniffed the sidewalk, or the sound of more tentative footsteps which indicated someone trying not to make noise. They had to get used to the sometimes-furtive comings and goings of young couples. They got a feel for the late-night rhythm of the very streets the criminal had walked for months with impunity.

Outside of the task force, others could not afford to be so patient.

Women were abandoning “commonsense” advice and taking matters into their own hands. If City Hall wouldn’t outline a plan to protect its citizens, they’d create the plan themselves.

— Jeff Schwaner is a journalist at The News Leader in Staunton and a storytelling and watchdog coach for the USA TODAY Network. Contact him at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

NEXT UP ON 'THE STOCKING MASK'

Sugar was even more animated than usual that night, Oct. 17, 1979.

It wasn’t bridge night, but the card table was out at Sugar Higgs’ Church Street house, and half a dozen folding chairs were occupied by neighborhood women.

It was the same room Charles Culbertson had spent hours in talking with Sugar over cups of iced tea or coffee, or something stronger, over the years.

This night, there was wine. Cigarette smoke hung in the air.

The same room, but something different about it. A shared determination permeated the room that the young Culbertson could only call “grim.”

“The purpose of this is to counteract non-involvement,” Sugar told the group. “We need to take a hand in our own protection and quit sticking our heads in the sand.”

The women began to plan. And Culbertson finally had a story to write, his first serious news story for The Leader after a few years of freelance features. He hoped it might help catch a predator.

PART 1: Serial rapist stalks vulnerable city while Staunton police, women’s college stay silent

PART 3: Cops admit predator is at large. Staunton women told to use ‘can of hair spray’ for defense.

PART 4: ‘Everyone’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them’

PART 6: ‘You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there’

PART 7: Women make demands. A psychic makes predictions. And a Virginia city holds its breath.

PART 8: Things go ‘round and round’: Two unlikely sources help police close in on Staunton predator

PART 9: After a year of dread and violence, a Staunton suspect confesses, but is there evidence?

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: With black man on trial, many doubt he's the Stocking Mask Rapist