‘We gotta wake this community up.’ The battle to preserve, restore Miami’s Black landmarks

Black landmarks tell a significant story of Miami. But for how much longer?

While many sites have been repaired, such as the Lyric Theater in Overtown, where educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune once lectured, and the Hampton House in Brownsville where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. once stayed, others are in danger of disappearing due to lack of funds, restoration complexities and a demand by developers to buy the land and build a big box store or other profitable structure on it.

Three generations of the Wallace family are mired in a bureaucracy thicket in their efforts to restore the Ace Theater, an Art Deco building that was built in 1930s’ Coconut Grove as a Blacks-only theater and community gathering place by the Wolfson-Meyer Theater Company, which became Wometco Enterprises.

For decades, the Wallace matriarchs have pushed to revive the venue as a center of community life and culture after West Grove businessman Harvey Wallace — the husband, father and grandfather of the Wallace women — bought the landmark from Wometco in 1979.

Nearly all of Miami’s Black landmarks are similarly threatened. Many remain painful vestiges of the Jim Crow era of racial segregation, a nearly 100-year stain on American history. As the debate rages over an AP African-American Studies high school course and whether to prohibit diversity, equity and inclusion programs at state universities and colleges in Florida, some may wish to strike these story-laden structures from memory. Or, at the least, pave them over.

READ MORE: If these walls could talk — landmarks tell story of Miami’s rich Black cultural history

Take Virginia Key on Biscayne Bay. Once Miami’s only public beach for Black residents— a historic landmark of the city’s segregated past — a portion of the picturesque spot has been championed as a fitting location for a civil rights museum for about 20 years.

The museum would rise atop Historic Virginia Key Beach Park that once was designated a “Colored Only” beach in 1945 — the same year World War II ended. The park earned its designation after a group of Black Miami residents staged a wade-in at Haulover Beach about 20 miles north, protesting the laws at the time that barred them from using South Florida’s greatest amenity — its beaches.

The Virginia Key museum would share Black Miami’s story and won taxpayer-funded support from voters in 2004. But bureaucracy and battles between Miami City Hall and Miami-Dade County Hall make it a nonentity for now.

READ MORE: This museum would tell the story of Miami’s segregated era. It has stalled for years

Not knowing Miami’s history

But what about the landmarks that are standing? They can’t thrive alongside apathy, the likelihood of redevelopment on valued land, and an attendant lack of awareness from the multitudes that have made Miami home during the last four decades.

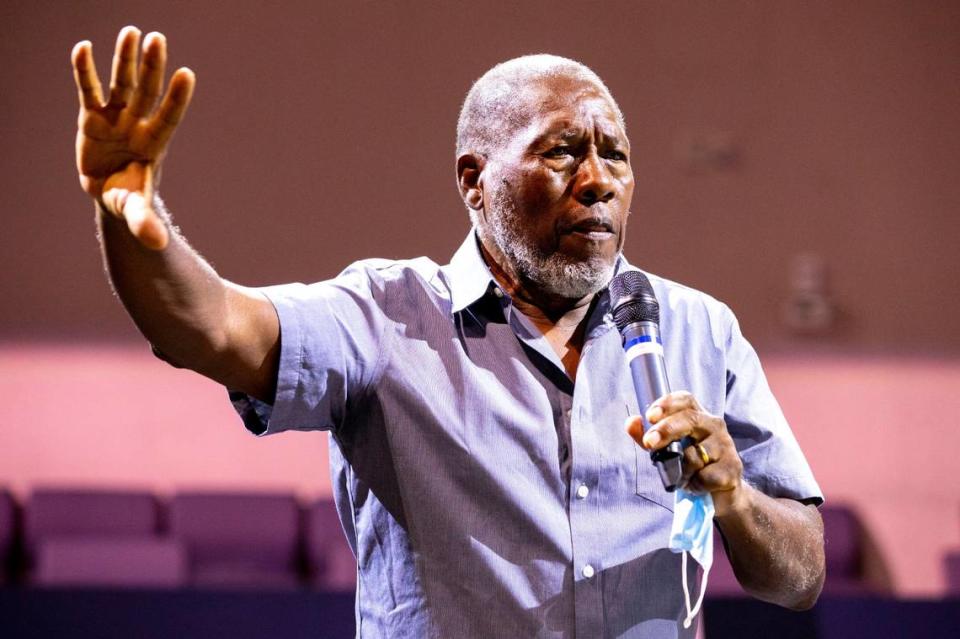

“So many people have come to Miami since 1980, for example, since the McDuffie riot,” said Miami historian and author Marvin Dunn, 82, a professor emeritus at Florida International University. “There are people here that don’t know there was a killing in the streets in Miami in 1980. ‘What? There was a riot here? I’ve lived here for 30 years and didn’t know that.’

“Because so many people are coming into the community and have historical attachments to other places, but not to Miami. They think Miami was born when Arthur Godfrey went live on television. So they are, what’s the right word, uninformed about the real long-term history of this community. Historically speaking, they just got here,” Dunn said.

More education, please

What’s needed, and what landmarks like the Hampton House, the Dorsey House, Georgette’s Tea Room and the Bethel House, among others, can provide if properly nurtured, is more education, said retired educator and civic activist Enid Pinkney and Sam Moore, the surviving half of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame duo Sam & Dave.

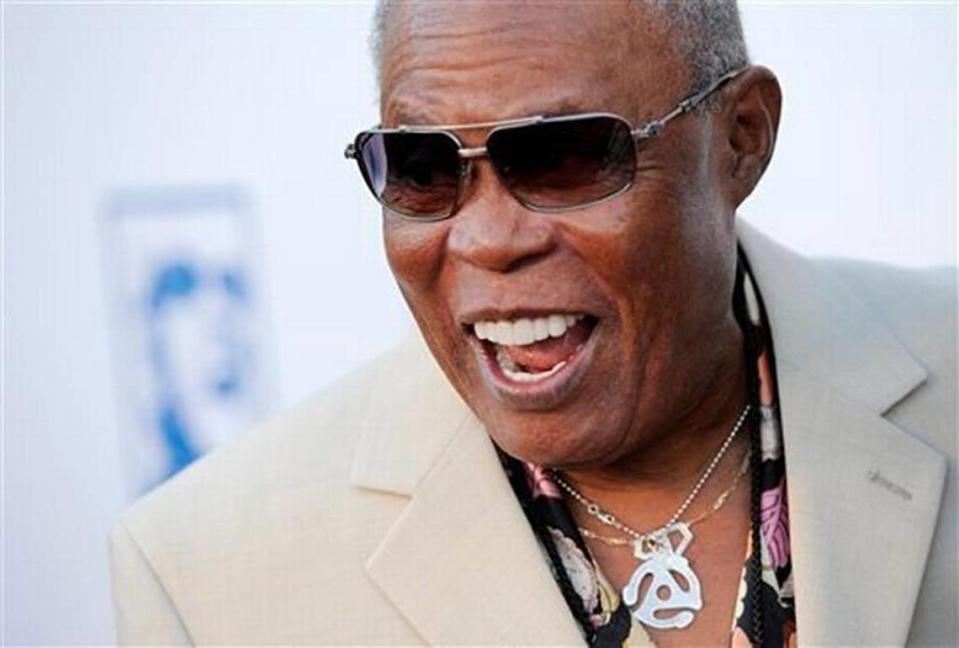

Moore lives in Coral Gables with his wife, Joyce, and is an artist in residence at Florida International University. In 2022, Moore was the inaugural recipient of the CARTA Medallion, given by FIU’s College of Communication, Architecture + The Arts.

Pinkney, 91, and Moore, 87, were both born in Miami’s Overtown neighborhood.

“More education. More history about the community and people learning about their heritage and the legacy that is a part of this community. And not only this community, but also Miami, especially in the Black community. Because I think that there’s a neglect when it comes to promoting Black history,” said Pinkney.

“We believe that it is critical to develop curriculum for both lower and middle schools, possibly even high schools, as part of Miami-Dade County cultural education,” said Moore, who met singer Dave Prater at the long gone King of Hearts club in Liberty City at 6000 NW Seventh Ave. in 1961, which led to the duo’s enduring classics like “Soul Man.”

“There are probably 50 million other things to do,” Moore said about preserving Black history in his hometown.

That, Pinkney says, takes funding and a will on the part of residents and elected officials.

“There’s usually no money whenever you go to try to get something done. It’s very scarce,” she said. “And a lot of the problem that I see is Black people don’t have that much clout in Miami. They just can’t get too much done. There’s always a blockage, always something that is stopping progress. And I would like to see progress made in education and educating young people about our history because a lot of people don’t even know that the Hampton House exists.”

Pinkney was instrumental in the restoration of the Hampton House and was the first Black president of Dade Heritage Trust, the nonprofit whose mission is to preserve Miami-Dade’s architectural history and cultural heritage.

“We gotta wake this community up so that we get some respect and we can pass on history and our heritage,” Pinkney said. “We’re like Rodney Dangerfield. We get no respect.”

Jacqui Colyer, Hampton House’s chairperson, is leading efforts to bring Hampton House out of the COVID-19 pandemic funk, which had dropped annual visits to the museum from about 15,000 people a year to 300 a month, or about 3,600 a year. Today, Hampton House, the last remaining Green Book hotel, is nearing its pre-pandemic draw.

Worry over real estate boom

“We need them because if we fail to look at our history, and remember our history, we continue to repeat it ... and then wonder why we’re not getting a different result,” Colyer said of the importance of keeping Miami’s Black landmarks standing.

At the very least, prominent Black Miami trailblazers say markers such as plaques ought to be placed where former Black landmarks stood.

“Placed at every significant Black historic location, whether it’s Overtown, Liberty City, Downtown Miami. For example, where the King of Hearts was located in Liberty City. Where Sam Moore and Dave Prater first came together as a duo in 1961. Flip Wilson also owned his craft on the same stage at the same time. It would be wonderful for there to be a historic display at Miami International Airport. At least one of the terminals should have a permanent display showing the great cultural impact” Blacks gave to Miami, Moore said.

Added Dunn: “After 42 years, we have finally gotten the state to put up a typical classical state historic marker where they killed Arthur McDuffie. That spot really changed Miami history.” The marker, still in the manufacturing process, is not yet placed but is expected some time in 2023, Dunn said.

McDuffie was the 33-year-old Black insurance agent and former Marine who ran a red light on his Kawasaki motorcycle on Dec. 17, 1979. That led police officers to chase him, finally stopping him at North Miami Avenue and Northeast 38th Street, where about a dozen officers beat him into a coma. He died a few days later in the hospital.

The acquittal by a Tampa jury of the four white police officers charged in McDuffie’s death led to three days of rioting in Miami in May 1980, leaving 18 people dead, 400 injured and $100 million in property damage from the burnt-out buildings.

READ MORE: The day Miami was rocked by riot after cops cleared in McDuffie beating

“[Miami] would lose the physical evidence of the history. Savannah has incredible monuments downtown — you can’t walk a block without passing two or three monuments. We don’t have that here. It is as if we were just born,” Dunn said.

Dunn also laments that plaques may have to stand in not only for lost landmarks but for some of the landmarks whose futures could be at risk.

“The physical structures are disappearing,” Dunn said. “That’s why it’s important to share this information. People need to know when they tear down these buildings that they are a part of Black history in this community.”

Some of these places may not be standing in 10 years — “or even next year, for that matter,” Dunn said, citing developers’ recent interest in land in South Florida’s Black communities.

“Whether it’s historic or not, it’s valuable land for housing and high-end stores. And so I’m very worried about these landmarks,” he said, mentioning the Hampton House.

“They put that building up, but the long-term extent of caring for it and staffing it and promoting it, that money is not there, which is why that building is empty most of the time,” Dunn said. “That’s not going to be able to go on forever. It’s a beautiful building. I’ve been in it many times. But it’s underutilized and therefore vulnerable to eventually being removed. Once somebody says, ‘Well, you know, we’re spending a lot of money down there and there’s no activity.’

“Same thing with the Lyric Theater but the Lyric Theater will probably survive,” Dunn said. “It’s such a huge monument I can’t imagine the wrecking ball on it. But the others we could talk about, yeah, it could be done.”

Reminders of Miami

And that, Dunn worries, would strip Miami of much of its storied character.

“To walk on that ground connects you with your history. And once that ground becomes the shopping center or a gas station or a Walmart — it’s all gone,” he said.

Some landmarks are especially stinging reminders of Miami’s Jim Crow era. Remnants of a 4-foot-tall, faded yellow wall remain near Northwest 12th Avenue between 62nd and 67th streets. The wall, dubbed the Segregation Wall, links Miami’s segregated past to its current cosmopolitan state.

The wall was built circa 1939 alongside a thicket of Australian pines and was originally 4 feet high in some spots, 6 feet in others, and ran adjacent to the Liberty Square housing project, according to Miami Herald archives.

“White folks at the time were concerned about Black folks coming out of these slums in Overtown and bringing disease into their home as housekeepers and maids,” Dunn told CBS Miami.

An upsetting relic, to be sure, but one that ought to remain, Dunn told CBS Miami. “They should never touch the wall. This is a sad reminder to Black people and to whites as to what we lived through in those days.”

‘Stories need to be told’

For another Miami historian, a handful of words changed the course of Dorothy Jenkins Fields’ life.

“’I guess those people haven’t thought enough of themselves to write their history,’” Fields recalled a downtown Miami librarian telling her in 1974 when her request for books about the history of Black South Floridians came up empty.

That ignited Fields’ fervor not just for documenting Black Miami history but preserving its landmarks. Since that encounter with the librarian, Fields founded The Black Archives, History and Research Foundation of South Florida Inc., a nonprofit that has been instrumental in saving the Lyric Theater, D.A. Dorsey House and the Ward Rooming House, all of which are integral threads of the Overtown tapestry.

Originally settled by Southern Black and Bahamian laborers, Overtown blossomed into a rich, entertainment district. Black musicians from Louis Armstrong to Ray Charles to Ella Fitzgerald dazzled crowds in the neighborhood, eventually earning it the nickname “Harlem of the South.”

Everything changed with the construction of Interstate 95. Under the guise of “urban renewal,” an entire community — and much of its history — was destroyed in the 1960s. The end of segregation also meant many sought shelter in new neighborhoods, taking their stories with them.

Others didn’t want to tell their stories. What was done to Black Miamians “kept some people from talking about their history,” said Patricia Jennings Braynon, chairwoman of the Black Archives. Braynon explained how Ku Klux Klan members once threw rattlesnakes on the porches of Black families to intimidate them during election season.

“I believe that these stories need to be told,” Fields said. “Sharing stories will help us as human beings to better understand each other and help us move forward.”

Here’s where some of those stories and others of triumph may be told:

Ace Theater

Wometco, the Miami movie house chain, opened Coconut Grove’s Ace Theater at 3664 Grand Ave. in the 1930s to serve the Black community.

The Ace was one of only 113 segregated movie theaters where African-American audiences could go to see a film in Florida from 1940 to 1953, according to Dade Heritage Trust. The Ace was the only entertainment facility to serve the Black community in Coconut Grove during the city’s segregation era, according to Miami’s Historic Preservation Board’s report on the theater’s designation as a historic site in 2016.

Black audiences from as far south as Key Largo came to see the latest screen adventures from Black actors like Lena Horne, Dorothy Dandridge and Lincoln Perry. Later, Westerns starring John Wayne, movies featuring Elvis Presley, touring stage shows featuring James Brown and black-and-white reels of singer Fats Domino finding his thrill on “Blueberry Hill” screened or played at the Ace.

This, along with activities like graduations and proms.

Ace entertained its last audience when Wometco shuttered the theater in the 1970s. Grove businessman Harvey Wallace, husband to Dorothy Wallace and father to their daughter Denise and grandfather to her daughter Nichelle Haymore, bought the theater in 1979. He intended to convert the structure into a five-story Bahamian marketplace with retail on the ground floor, an auditorium for entertainment on the second floor, and apartments on the top floors, Fields wrote in a Herald column in 2021.

But the McDuffie riots in 1980, along with a nationwide recession, stymied funding and the Ace sat vacant.

The Wallaces were unbowed. After Harvey died in 1988, his wife and daughter, later joined by his granddaughter, determined to get the Ace back in play.

The process has been challenging.

On the plus side, Miami’s Historic and Environmental Preservation Board designated the Ace a historic site in 2014. In 2016, Dorothy and Denise Wallace’s efforts led to the theater’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2021, the National Park Service awarded a $398,199 grant to help bolster the Ace Theater Foundation, the Miami nonprofit run by Patricia Wooten. The restoration work has begun, including on the distinctive but weathered ACE marquee, Denise Wallace said.

But more needs to be done to bring the Ace up to code. Wallace said she will make her case on Wednesday, Feb. 8, at a hearing with the National Park Service and the city.

Wallace said once restoration work gets underway and is finished, the foundation would turn the Ace, “back into its original purpose as a multipurpose community facility,” she said.

But don’t look to the Ace to become solely a movie theater, she said. The market for movie theaters is cratering post-pandemic as viewing habits have shifted. Witness the announcement in January of the planned closing of the Regal South Beach multiplex.

Wallace said the foundation is considering a flexible floor plan that could allow for a “multipurpose community center” that could host small concerts, lectures, recitals, film screenings and other events.

The Ace “was open in a dark period of our nation’s history,” Denise Wallace said. “That’s a fact. We’re not going to gloss over that fact. We’re not going to diminish that fact. It was built as a Jim Crow movie theater. You can’t negate that.

“However, out of that history, what I found is that the Ace also served people and there were just so many wonderful lessons that the neighborhood kids learned. So those are stories and we have some of those stories recorded and those are the stories that [we] want to tell.”

Bethel House

The Bethel House was built in 1937 by African-Bahamian settlers who arrived in Dade County in the early 1900s. “The last standing pioneer era house in Perrine,” said Miami preservationist Helen Gage.

Gage led the effort to preserve the house after it was set for demolition in 1995, three years after Hurricane Andrew devastated the South Miami-Dade area. But the storm didn’t destroy the hardy Bethel.

In 1996, Bethel House was designated as a historic site and, with assistance from Miami Habitat for Humanity and Miami-Dade County, Bethel was relocated a few doors down from its original spot to its locale at 18201 SW 102nd Court in Perrine.

By 2006, the Bethel House was “fully restored and rehabilitated” with funding and assistance provided, in part, by the County’s Task Force on Urban Revitalization, Gage said.

Bethel operates as an African-Bahamian museum.

“Our programming and events center on educating the youth and current community residents about the original African-Bahamian settlers of Perrine and the history they paved,” Gage said. “This information is not typically passed down to the next generation, nor is it taught in our schools. Thus, it is up to the elders of the community and the Bethel House to educate younger generations.”

Among its programming: a touring Perrine Pioneer Exhibit that travels to schools, churches and community centers. Bethel hosts the planting of native Bahamian plants and Bahamian Independence Day celebrations.

Future plans for the Bethel House include the addition of a covered terrace to accommodate a larger audience and a “face-lift” in the summer.

“Funding and donations are always welcomed,” Gage said. “However, we would love to gain more traction and recognition from nearby communities to guarantee our longevity.”

When Bethel opened its refurbished doors in December 2006, Gage, a native of Key West, told the Herald: “A lot of the community didn’t understand. They just saw it as a little raggedy house. But I had faith. I told them, ‘If [Hurricane] Andrew didn’t blow it down, it was meant to stay.’ ”

The Dorsey House

Located at 250 NW Ninth St., the Dorsey House belonged to D.A. Dorsey, Miami’s first Black millionaire, who made his fortune building residences throughout Overtown. He organized South Florida’s first Black bank and bought Fisher Island, then 21 acres, in 1918 so Black families would have a beach. The home, which was constructed in 1915, still stands at its original location thanks to the use of stone in its construction.

By the 1980s, however, the home was in disrepair. The city had even designated it for demolition. That is, until Fields swooped in.

“It’s important for me and for everyone to know that we didn’t all live in three-room houses,” Fields said of the home. “I wanted to show a level of affluence.”

By 1983, Fields had gotten the Dorsey House designated as a local historic landmark. By 1989, it had been added to the National Registry. By 1995, the home had been reconstructed, with its final renovations completed in 2019.

“It is something that shows the kids in the neighborhood that there is Black excellence within arm’s reach,” said Kamila Pritchett, the executive director of the Black Archives.

Nowadays, the Dorsey House has doubled as a museum and a gallery. Featured inside the home has been everything from exhibits on Dorsey himself, the Great Migration and, currently, a showcase of multimedia art in collaboration with URGENT Inc., a nonprofit focused on empowering Black and brown youth.

“I think it’s important for kids, who literally walk past this house all the time and probably don’t even know what it represents, to understand the story behind it,” Pritchett added.

Georgette’s Tea Room

Georgette’s Tea Room is named for Georgette Scott Campbell, a Georgian who moved to Miami in 1917. Campbell and her sister Willie owned and ran the Royal Cafe in Overtown. In 1934, Campbell moved to New York to open a tea room in Harlem where she gained renown as a hostess.

She took that reputation back to Miami by 1940 when she opened Georgette’s Tea Room in Miami’s Brownsville neighborhood.

The 13-room house was built to her specifications in Streamline Moderne Style at 2540 NW 51st St. Georgette’s soon became the must-stay residence and meeting spot for Black entertainers like Nat King Cole and community activists who wanted a more secluded hideaway from the bustle of Overtown at the time. The Black celebrities also could not stay at the Beach hotels in which they performed.

By the 1950s, jazz singer Billie Holiday had a permanent room in her honor at Georgette’s. On one of her visits, Holiday, who frequented Miami until her death at 44 in 1959, had a group of Miami area schoolteachers rapt at a luncheon in one of the rooms. The lavish table was festooned with fancy silverware, flowers and, certainly, tea.

“I mean, this house, when you walk into it, it just has such a presence and the history is so steeped in it,” said Kim Johnson, the project manager behind Georgette’s renovation. “It’s almost as if it speaks to you, ‘Please restore me.’ And I am in awe every time I go there. It’s just like, Wow.”

The tea room’s namesake died in 1962 and Georgette’s Tea Room was designated historic in 1990, according to The New Tropic. Georgette’s is owned by Bethany Seventh-day Adventist Church and has received a $215,000 grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund for exterior work, which is nearing completion. Johnson estimates the house needs about $750,000 for interior work renovations and is raising funds.

“We have to keep it,” Johnson said, recalling how one of Campbell’s goddaughters contacted the current owners to tell of her childhood at Georgette’s. The woman told them how, as a young girl, she watched the beloved entertainer Louis Armstrong, a frequent guest, walk around Georgette’s playing his trumpet and drinking “Scotch and milk, all the time.”

“We’re hoping it’ll be a small event place for small events,” Johnson said of plans, citing the photo of Billie Holiday and the teachers as the kind of luncheon a new Georgette’s could host.

“We definitely want to have a reading room for our kids in the community. Blacks couldn’t go to a hotel for their honeymoon. So they spent their honeymoon at Georgette’s Tea Room house. So we want to share the history. We want to have an annual tea party,” Johnson said.

“The main thing is to share the history so that we will not take what we have right now for granted,” Johnson said. “Someone before us paved the way.”

Hampton House

One of the world’s most quoted and revered speeches reportedly took shape inside a room tucked inside the Hampton House at 4240 NW 27th Ave.

In 1963, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., worked on drafts of his “I Have a Dream” speech that he would deliver during the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. King reportedly tried some of his drafts out from inside a room on the first floor of the Hampton House.

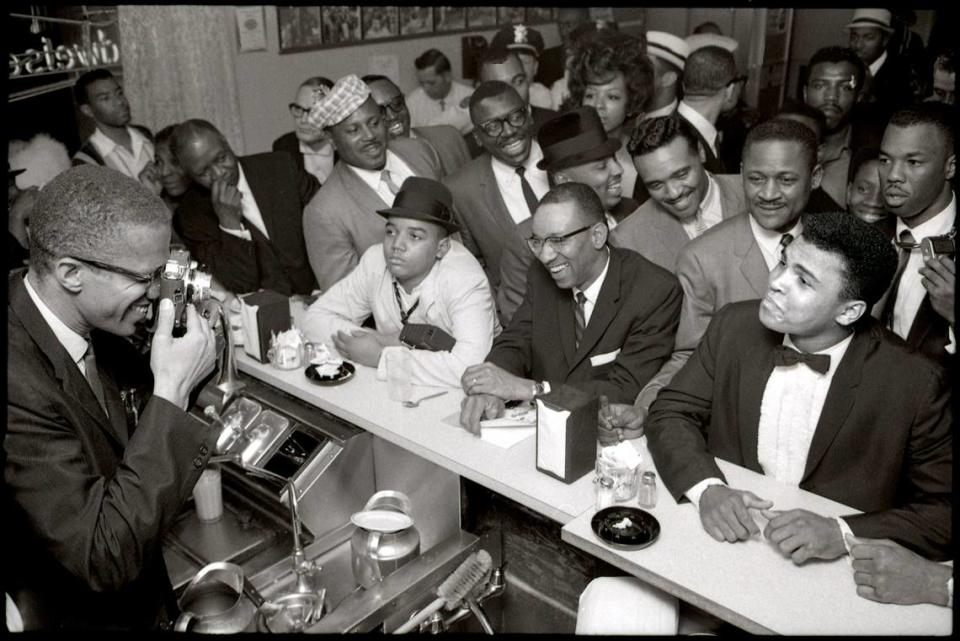

He liked the tranquility of that particular room. The setting let him think. And write. And meet with other civil rights organizers to plan strategy. That’s because places like the Hampton were where people like King and Sammy Davis Jr. and Muhammad Ali and Jackie Robinson stayed when in Miami.

“He was working on a speech in his room, and he wanted everyone to sit down and listen to it,” Charlayne Thompkins, former president and CEO of Hampton House, told the Miami Herald in 2020. “It was the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. So he dreamt the dream here.”

The Hampton House opened in 1955 and closed in 1976. Through Pinkney’s efforts, the venue was restored and reopened as the Historic Hampton House as a nonprofit museum and community center in 2015.

“We are doing OK, but not great,” said Chairperson Colyer. The museum costs about $1.5 million to $1.7 million a year to run.

“We don’t receive the kind of funding that the other museums are seeing. We’ve got a lot going on but it’s all about resources and funding and that continues to be our struggle,” Colyer said.

“I’m glad that it’s open and that it’s available to the community,” said Pinkney, the renovated Hampton museum’s founder. “But I would like to see the community using it more. I would like to see more activities going on at the Hampton House. And, of course, that requires more support and more financial support to do some of the cultural activities I’d like to see going on.”

Red Rooster

The 2020 opening of esteemed chef Marcus Samuelson’s Red Rooster Overtown presented a distinct merge of past and present. Prior to the Bib Gourmand-rated restaurant, the space was home to Clyde Killens Pool Hall, which Killens himself described as “the classiest operation around” that was frequented by Muhammad Ali, boxer Archie Moore and comedian Flip Wilson.

“Always someone big in there,” Killens, a Black promoter during Overtown’s heyday, told the Miami Herald in 1990.

Walking inside Red Rooster can feel like stepping into a different time. Odes to Overtown’s history are plastered all along the restaurant’s walls. Green Books. Concert posters. Black-and-white photos. Even the restaurant’s upstairs portion, aptly named the Pool Hall, has emerged as a hot spot for Black locals and travelers alike thanks to parties like Groove Theory and The Shrine.

“I’ve turned down many venues because it doesn’t align with what I do: create safe spaces for Black people,” said Simone Russell, the brains behind Groove Theory, a Friday night homage to soul. Miami nightlife is still segregated, she continued, yet the Pool Hall is “a place for people to still let loose, have fun and have community.”

“In other locations, we have to be concerned with catering to a more diverse audience,” added Jason Panton, who started The Shrine, a Saturday celebration of Afrobeats and dancehall. “This is one of few places that have the cachet, the respect internationally and locally and we do not have to dilute what we’re doing: We’re serving our culture and it’s unapologetic.”

Pritchett credits Fields for planting the seed that has blossomed into an entertainment district, somewhat of a full circle for Overtown.

“The bonus thing you’re getting is an arts and cultural complex and that’s a direct result of preservation,” Pritchett said. “This whole complex wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for the preservation efforts of Dr. Fields to save this space. So the smart thing to do is use this space to generate the revenue needed to support something that people aren’t necessarily throwing their money at.”

Adds Derek Fleming, partner at Red Rooster: “What comes out of Overtown — rich artistry, rich music, rich cuisine, rich design — all these things are part of what makes Miami special as a whole.”

Ward Rooming House

A similar transformation has happened across the street at the Historic Ward Rooming House. Built in 1925 by Shaddrack Ward, the Ward Rooming House was a place where travelers of color could lay their heads. The Ward family managed the home which, for some visitors, served as “transitional living,” said Christopher Norwood, the founder of Hampton Art Lovers, a gallery housed inside the Ward.

If Black people came to Miami in search of relatives “you got a room at the Ward and you found them,” Norwood continued.

More than just a place of refuge for the Black community, the Ward also housed traveling Seminole Indians.

“When the Indians would come downtown to sell their wares, they also, because they were people of color, had nowhere to stay,” said Patricia Jennings Braynon, Shaddrack Ward’s great-granddaughter and chairwoman of the Black Archives.

At its peak, the Ward had multiple buildings that also served as a meeting place for various fraternities, sororities and social clubs. The Ward was similar to the Dorsey House in that it, too, was built with stone, which explains how it remained a working rooming house until the 1980s, Norwood said.

In later years, it declined until Braynon’s great-aunt sold the property to the city of Miami in 2004. After a million-dollar investment, the city designated the property as a historic site in 2006. To have such a personal part of her family’s history enshrined for perpetuity is huge for Braynon, who encourages others to find a way to remember their ancestors.

“It builds that sense of pride throughout the family,” Braynon said.

The specter of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ assault on Black history has also weighed heavy on Braynon’s heart and furthers her point about preserving history: “If we do that, it doesn’t matter what some random person says about an individual because you know who your people are and where they came from.”

Since the mid-2010s, Norwood has used the space to let art teach the history of Overtown and beyond or, as he puts it, “We use art to build community.”